When it Comes to Forest Health, Prevention is Key

New research pinpoints how we can take action to stop the spread of invasive pests traveling along the global supply chain.

North America’s forests are at risk. Every year, insects and diseases damage an average of 50+ million forest acres in the USA—and another 40 million acres in Canada—critically harming up to 15% of forest cover. While some of these forest insects and diseases are native to their ecosystems and their actions are part of the natural cycles of forested areas, others are non-native invasive species that damage and kill trees at uncontrolled and accelerated rates.

In fact, invasive pests can drive the elimination of an entire tree species from a forest.

Trees like the American elm and American chestnut have been lost from our natural forests because of severe damage from invasive forest pests.

Our global insights, straight to your inbox

Get our latest research, insights and solutions to today’s sustainability challenges.

Get Our NewsletterIt has required breakthroughs from multiple generations of scientists to bring these trees back from the brink—and ultimately, success is not guaranteed. It’s far better to prevent forest pests from reaching our trees and forests in the first place, whenever we can, to learn from this tragic history and act to prevent future catastrophes.

It’s important to know that invasive insects like the emerald ash borer and spotted lanternfly didn’t get to North America on their own; they reached our forests accidentally through international trade.

Wood packaging material is historically a leading pathway for entry of wood-boring invasive insects.

And the impact of wood-boring insects—the kind that might infest an untreated wood shipping crate, pallet or spool—can be really severe.

These invasive pests change the natural dynamics of the places they invade by reducing biodiversity, altering ecosystem function, and sometimes functionally eliminating entire species of trees from the forest. And we know that forests damaged by insects sequester 69% less carbon than a healthy forest—meaning that invasive forest insects can cripple one of our most important tools for fighting climate change through natural climate solutions.

But there is hope.

Thanks to new research we now have a better understanding of how and when these pests enter and leave the international supply chain at very precise points.

What and Where are the Weak Links?

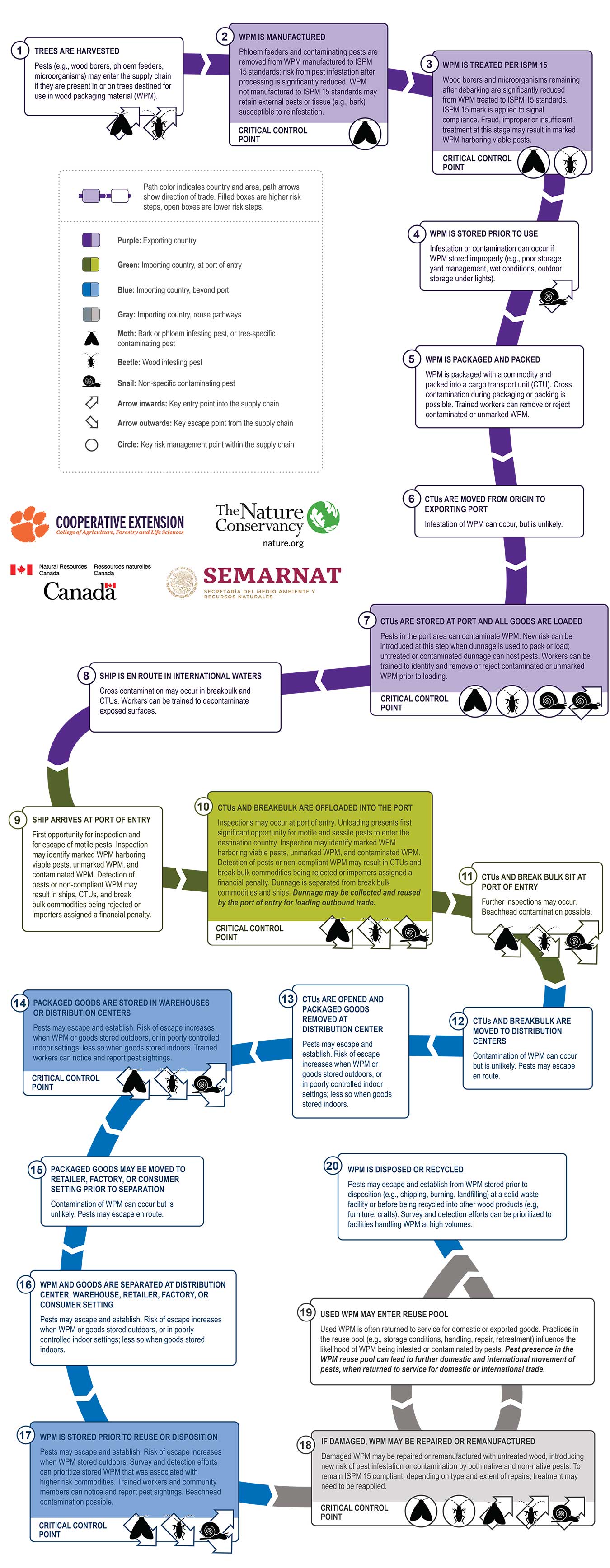

Study authors developed an infographic to show critical control points where pests are most likely to enter and leaave the supply chain.

A study led by TNC with funding from the US Forest Service, in partnership with Clemson University and national forestry agencies in Canada and Mexico, spotlights the most serious risk points so decision makers can focus on effective actions to prevent the spread of invasive species.

The governments of more than 180 countries—along with all the private industry trade partners that buy, sell, move, and run the logistics of goods flowing around the world—each have a role to play in reducing the movement of pests on wood packaging material and holistically protecting our planet’s forests.

Key Takeaways from the Study

Governments Should Reinforce Existing International Regulations

In 2005, an international regulation known as ISPM 15 was implemented across North America, requiring all solid wood packaging material be treated to kill pests before international shipment. A recent analysis showed this regulation, which was created in response to serious pest infestations caused by untreated wood packaging in the 1990s, has reduced the presence of live pests in wood packaging to about half of the pre-implementation rate.

But the same research also showed that this reduced rate has remained stubbornly the same for the last 20 years. The reasons for that aren’t entirely clear, but it could be some combination of possibilities: fraud, the unintentional use of untreated wood, insufficient treatment levels, or incomplete treatments applied to wood before it is made into solid wood packaging material.

The problem is we don’t know which of those factors are causing the ongoing presence of wood infesting pests in solid wood packaging. That’s incredibly frustrating, because to do a good job at mitigating risk, we need to know what’s driving these failures. For instance, addressing recurring fraud would require a different set of tactics than addressing insufficient kiln temperatures in countries with very cold winter climates.

Quote

Given the ever-increasing volume of international trade, there’s no time like the present for researchers and policy makers to dig into what’s driving these ongoing problems.

Filling this knowledge gap will require a lot of cooperation. And given the ever-increasing volume of international trade, there’s no time like the present for researchers and policy makers to dig into what’s driving these ongoing problems. A science-based approach focusing on the collection and sharing of data from across North America and around the world will show the international community the most effective places to act to increase effectiveness of ISPM 15.

Contaminating Pests Require Integrated Approaches

The signs of a tree ravaged by the spotted lanternfly are easy to see: sticky, odorous ooze, sooty mold, and hundreds of jumpy, flappy, grabby, brightly colored insects. But the signs of spotted lanternfly contamination on a wooden shipping crate are much harder to detect: just a small gray smudge of the insect’s egg cluster that might be hidden in a crevice or crack. Now imagine trying to find one of these small gray smudges on the billions of crates, pallets, containers, and vehicles that are constantly moving goods around the globe.

Global supply chains do have some voluntary best practices, and a few specific regulations, that are aimed at reducing contaminating pests. However, the current system is not consistent among the world’s regions and trading partners, and it is often targeted to prevent very specific pests. These limitations create gaps where new or unexpected contaminating pests could move unnoticed in trade. Consistent global regulations for preventing, removing, or treating wood packaging for contaminating pests before that pest-ridden packaging can enter the supply chain would be significantly more effective than the current patchwork of systems in place.

Quote

Consistent global regulations for preventing, removing, or treating wood packaging for contaminating pests before it can enter the supply chain would be significantly more effective than the current patchwork of systems.

Strategies that reduce the presence of contaminating pests must be effective on each component part of international trade, not just wood packaging material. Contaminating pests are a problem on all the surfaces moving in the supply chain, including shipping containers, commodities like tile and stone, and even ships and trains themselves. And it’s crucial to know that the regulation that protects from wood-specific pests listed above, ISPM 15, is not designed with the intent to address contaminating pests. These pests—as variable as snails, moths, wasps, frogs, and more—are too different, and therefore they need their own targeted preventative mechanisms and policies.

The international community is working hard on the complex issue of contaminating pests. It is likely that interventions are needed at multiple points within the supply chains to create a system that protects against this complex challenge. The threat of contaminating pests should be met head on by supporting many approaches, from better wooden pallet storage practices to new international regulations on the cleanliness of sea containers.

The Future of Forest Pests

The history of forest pests is already written. Without preventative measures targeted against solid wood packaging material, invasive forest insects and diseases were able to enter North America.

But the future of forest pests hasn’t been determined. The international community of scientists, tree advocates, and private industry partners can work together to create systems that protect both trade and trees across the globe. By strengthening the weak links in the current systems, beginning with the practices, and policies identified in this tri-national research collaborative, we can use science-based approaches to write a new future with fewer threats to trees around the world.

Download

Study authors developed an infographic to show critical control points where pests are most likely to enter and leaave the supply chain.

Download See the Full Study