Exacerbated by climate change and years of severe drought, wildfires in the American West have posed significant—and increasing—safety, health and environmental threats in recent years. In 2020 alone, high-intensity fires resulted in at least 46 deaths and nearly $20 billion in damages in the United States.

There are many tools that can help make our landscapes and communities more resilient in the face of record-breaking wildfires. Among these are proactive management of forests using mechanical tree thinning and prescribed fire, also known as controlled burning. Within communities themselves, approaches include retrofitting buildings so they are less flammable, creating “defensible space” around structures, helping businesses develop disaster continuity plans, and ensuring at-risk individuals are prepared to deal with smoke from controlled burns and wildfires.

Chris Chambers has used all these tools and more. For the past 19 years, Chambers, who has a degree in forest ecology, has served as the wildfire division chief for the City of Ashland’s Fire & Rescue Department in Oregon. Before that, he worked for the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management.

Nestled in a valley beneath 7,500-foot peaks, Ashland is an idyllic community of about 21,000 residents that attracts some 350,000 visitors each year. But it’s also where the Almeda Fire sparked in 2020, causing more than 40,000 people to evacuate. Though the fire burned only 3,200 acres, it destroyed over 2,600 structures, displaced around 10,000 residents and killed 3 people. Chambers saw the devastation firsthand, as he and nearly all his fellow Ashland firefighters helped fight the fire. Although the blaze started just inside the city limits of Ashland, winds drove it northwest, and Chambers’ community didn’t experience the level of destruction that the towns of Talent and Phoenix did.

Residents Take Action

For Chambers, the Almeda Fire served as a tragic reminder of the steps his community needs to take if it wants to avoid the devastation that neighboring towns endured. The fire also raised awareness of the threat of wildfire among the residents of Ashland. Fortunately, Ashland recently secured a $3 million grant from the Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA) earmarked for mitigating risks from disasters like flooding and wildfire, enabling them to build on community interest and expand their mitigation actions.

“The City of Ashland and the benefitting residents match this funding by paying 25 percent of the cost,” Chambers said. “This money is helping us reduce flammable landscaping in yards, and we’re using these funds to work on and around 1,100 previously identified, at-risk homes. On the most vulnerable of these homes, we’re working to replace outdated, wooden roofing.”

Ashland has also created a fire-awareness program for real estate agents and inspectors, because “people often invest significant money in the homes they purchase,” Chambers said. “The program is helping new homeowners prepare their homes for fire.”

Forest Management is Part of the Plan

Of course, prescribed fire has been and remains a critical tool in Ashland’s efforts to prepare for inevitable wildfire. Over the past 10 years, the Ashland Forest Resiliency project has used controlled burns and conducted forest thinning to reduce excess trees and shrubs on more than 13,000 acres in town and nearby within the Ashland Watershed—the source of the city’s water.

Using prescribed fire to better prepare Ashland and its residents for wildfire has its challenges, though. In most cases, fire crews can ensure smoke from prescribed burns doesn’t settle in town, but not always. To address health concerns related to smoke from prescribed burns—as well as the smoke from wildfires, which is typically much worse—the community created a program dubbed "Smokewise Ashland."

This program—which involves the Chamber of Commerce, the local school district and university, the local hospital and others—disseminates important smoke-related information and has provided 600 high quality air purifiers at no cost to the most vulnerable residents of Ashland.

“As we improve this program, we are finding there is more support within Ashland for our prescribed fire efforts,” Chambers added.

Ashland: One of Many Communities Adapting to Fire

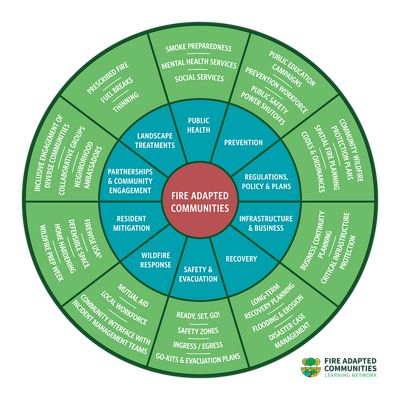

There are many leaders like Chambers urgently working to prepare their own communities for fire. Unfortunately, there aren’t many sources of support for these leaders, monetary or otherwise. This gap in support is why The Nature Conservancy and The Watershed Center partnered to create the Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network, or FAC Net, in 2013.

“FAC Net has been really helpful and has informed our program a great deal,” Chambers said. “The information the network shares and the exchanges it facilitates enable us to see what’s working and what hasn’t worked in other communities. Plus, there’s a lot of value in knowing you’re not alone out there. It’s super helpful to get on the phone with colleagues. And it’s a great way to advance fire-related science and knowledge.”

Successful community wildfire adaptation efforts are grounded in the particular strengths and needs of the community, so they can look quite different from place to place. Read on to learn about community adaptation initiatives in Colorado and New Mexico.

Close Call in Durango, Colorado

In southwest Colorado, jagged mountain peaks and towering ponderosa pines make for stunning views. But this landscape is repeatedly threatened by wildfire. That’s why the work of the local nonprofit Wildfire Adapted Partnership (WAP) is so critical. Ashley Downing, area resident and executive director of WAP, said its team of experts offers risk assessments to help residents protect their property. WAP also offers funding incentives to make it easier for people to remove dead and unwanted trees, and it subsidizes other opportunities to help safeguard homes and businesses. Much of this work is accomplished through a neighborhood-level approach.

“We have a network of about 135 ambassadors who represent high-risk communities,” says Downing. “They work to motivate neighbors to actively mitigate risk, plan for evacuations and tackle other ways to manage fire.”

Quote: Ashley Downing

It is amazing to have (FAC Net) serving as a connector among others working to make communities across the country more resilient.

Their efforts are paying off. One community that worked with WAP for years to clear brush and make homes more fire resistant saw the results of its efforts when a 2018 blaze approached. According to Chief Hal Doughty with the Durango Fire Department, “As the fire moved into that area, what we found is that the mitigation work did what it was supposed to do. We were able to save every single structure in that area.”

Santa Fe, New Mexico Prepares for the Next Wildfire

The Nature Conservancy and the Forest Stewards Guild are two of the 13 groups behind the Greater Santa Fe Fireshed Coalition, which is improving the health and long-term resilience of forested watersheds and communities. The group, formed four years after the 156,000-acre Las Conchas Fire and subsequent flash flooding in 2011, prioritizes work in communities as well as in adjacent forested landscapes. Projects are designed with community and natural resource protection in mind.

As one of the original members of the Fire Adapted Communities Learning Network, the Guild, along with the Santa Fe Fire Department, have been instrumental in helping residents and businesses prepare for wildfire.

Santa Fe falls squarely within the Rio Grande Water Fund’s (RGWF) project area, and the coalition’s goals are aligned with those of the RGWF. The RGWF is one of 34 water funds TNC has created in 11 countries. These multi-stakeholder groups secure funding for forest restoration and maintenance from entities that depend on those forests for their water supplies.