Working with Fire

Using controlled burns to keep Maryland’s forests and wetlands healthy.

Fire is a natural process—like rain. Many of the native plants and animals that call Maryland home have evolved to thrive with periodic episodes of natural fire.

One of the most reliable ways to boost forest health is by reintroducing fire. In 2020, TNC celebrated 30 years of conducting controlled burns as an ecological management tool in the state of Maryland.

As an organization, TNC has been burning for 60 years, become the world’s leading environmental nonprofit that conducts planned, controlled burns with more than 400 qualified fire staff and volunteers in 35+ states.

Returning fire to the landscape at a meaningful scale to keep our forests healthy and connected requires diverse skills, experiences and partnerships, as well as a new generation of fire practitioners who will carry the mantle for the next 30 years.

The Benefits of Fire

The benefits that fire can bring to a landscape are remarkably varied. Many species of plants and trees have evolved to be fire-adapted, and may not grow or disperse their seeds until after a forest has burned.

Fire enhances a forest’s overall biodiversity, and by doing so, makes it more resilient. When a stand of trees includes many different species rather than a few, they’re less likely to be wiped out by threats like pests or disease. And that resilience is crucial for the species and communities that depend on the services a forest provides.

Research suggests that fire also reduces tick populations, including the Lyme disease-carrying deer tick. Sideling Hill Creek has hosted one study conducted by Frostburg University professor Rebekah Taylo to measure tick populations and the presence of Lyme at burn sites at the preserve.

As an additional benefit, controlled burns help remove the buildup of dry wood and organic matter on the forest floor, which reduces the chances of dangerous wildfires and their severity if they happen. This also results in more open, spaced out forests that make it harder for destructive pests like pine beetles to kill trees across a massive range.

Technology on the Fire Lines

Shovels, chainsaws, drip torches, amphibious vehicles—and now ignition drones. These are just some of the technologies and equipment that TNC's fire practitioners use on controlled burns.

Prior to the burn, planning teams use geographic information systems (GIS) mapping tools, custom-built weather monitoring stations, data visualization tools and other technologies to create burn prescriptions. After the burn is complete, stewardship staff use LiDAR satellite imagery, acoustic bird recordings, wildlife cameras and other technologies to monitor the impacts of the burn.

To achieve our goal of returning fire to the landscape, we are deploying some of the most advanced technologies and scientific practices that allow us to burn more acres, faster and more safely than ever before.

Improved safety conditions for burn crews are one of the many benefits of the new IGNIS ignition drones by Drone Amplified. Without them, burn crew members must walk through the middle of a burn unit using handheld drip torches to get fire on the ground. This practice leaves crew members exposed to hazards like ticks and unsteady terrain.

With the IGNIS drone, burn crews are primarily responsible for burning and monitoring the perimeter of the burn unit, while the drone drops small incendiary spheres into the interior of the unit.

Along the same lines as the IGNIS, our burn crews have recently added another high-tech product to the toolbox. PyroShot is a gas-propelled, hand-operated mechanism resembling a paintball gun that launches incendiary spheres. Like IGNIS, PyroShot allows burn crews to more easily get fire into hard-to-reach places.

These and other technologies are leading to a high conservation return on investment. As early adopters that are willing to experiment with new and emerging technologies, TNC’s on-the-ground conservation practitioners play an outsized role. Now partners are looking to us for new best practices.

Understanding Historic Fire Patterns

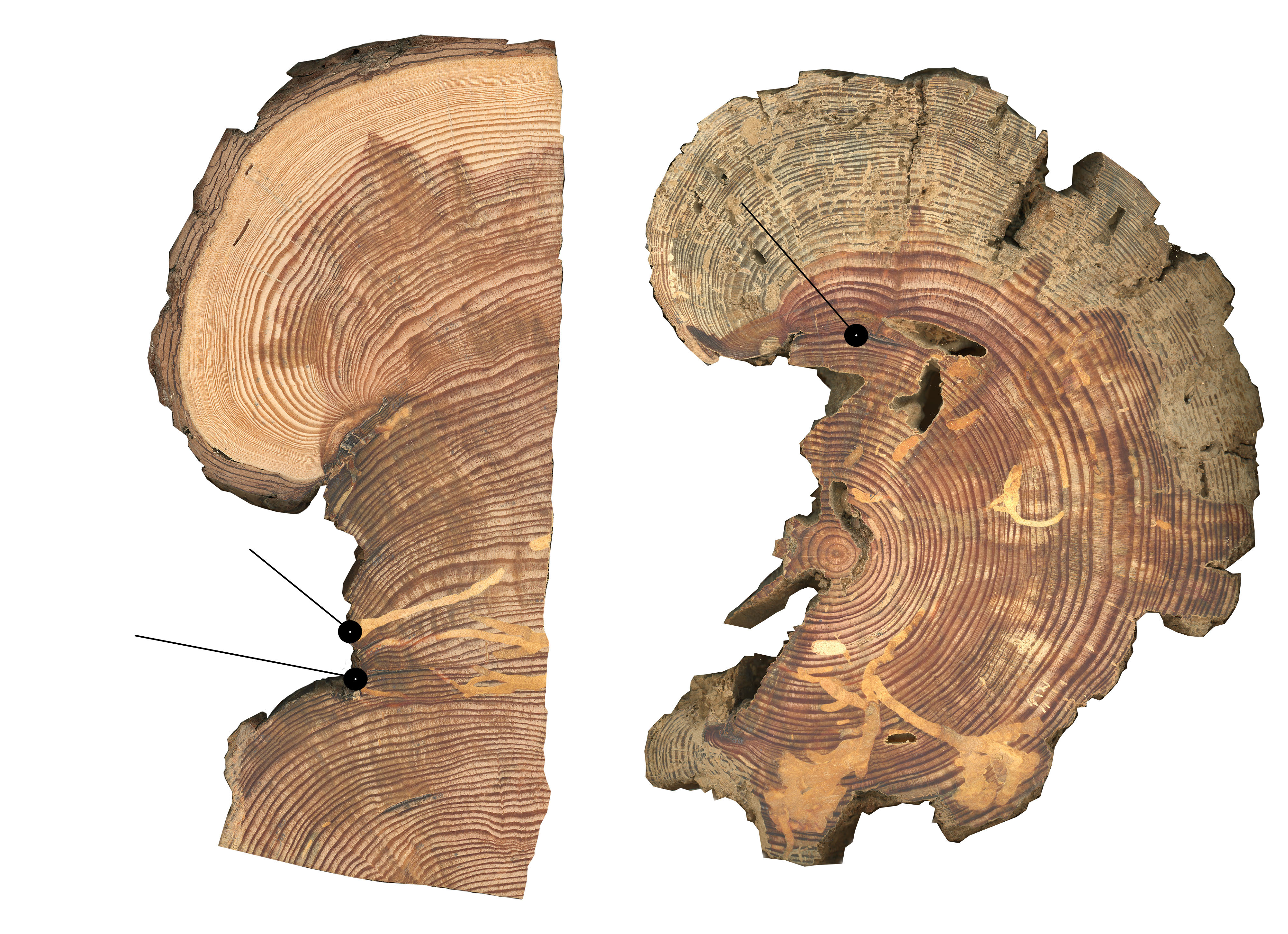

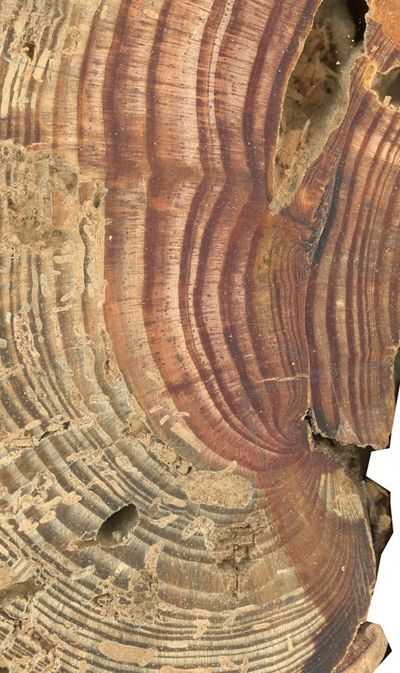

The more we understand about how and when fires occurred historically, the better we can replicate those natural events through safe controlled burns. There’s a story behind each growth ring and understanding those stories can help us protect and manage our forests into the future.

Telling the Story of Fire

The science of tree-ring dating, or dendrochronology, tells us more about a tree than just its age. Tree rings present an intricate story of the climate and environment in which the tree grew each year of its life.

As part of a dendrochronology study of forests in western Maryland conducted in collaboration with Dr. Lauren Howard of Arcadia University, MD/DC Conservation Steward Gabe Cahalan has been connecting the stories of tree rings with our human stories. Gabe has compiled more than 100 newspaper articles dating back to the early 1800s and matched three dozen articles to fire scars from trees within the study site on Catoctin Mountain.

Fire History and Dendrochronology

Read the Full StudyTheir study was published in the journal Fire Ecology in March, 2021. It concluded that fire was a key historical ecological factor on Catoctin Mountain from at least 1702 through 1951 and that returning fire to the landscape through controlled burns could help improve biodiversity and regeneration of the historic mix of pine and oak species.

Reading a Fire’s History

When we compare the story of one tree with the stories of dozens of others within a given landscape—or with the written historical record—a fuller, and sometimes smokier, picture emerges.

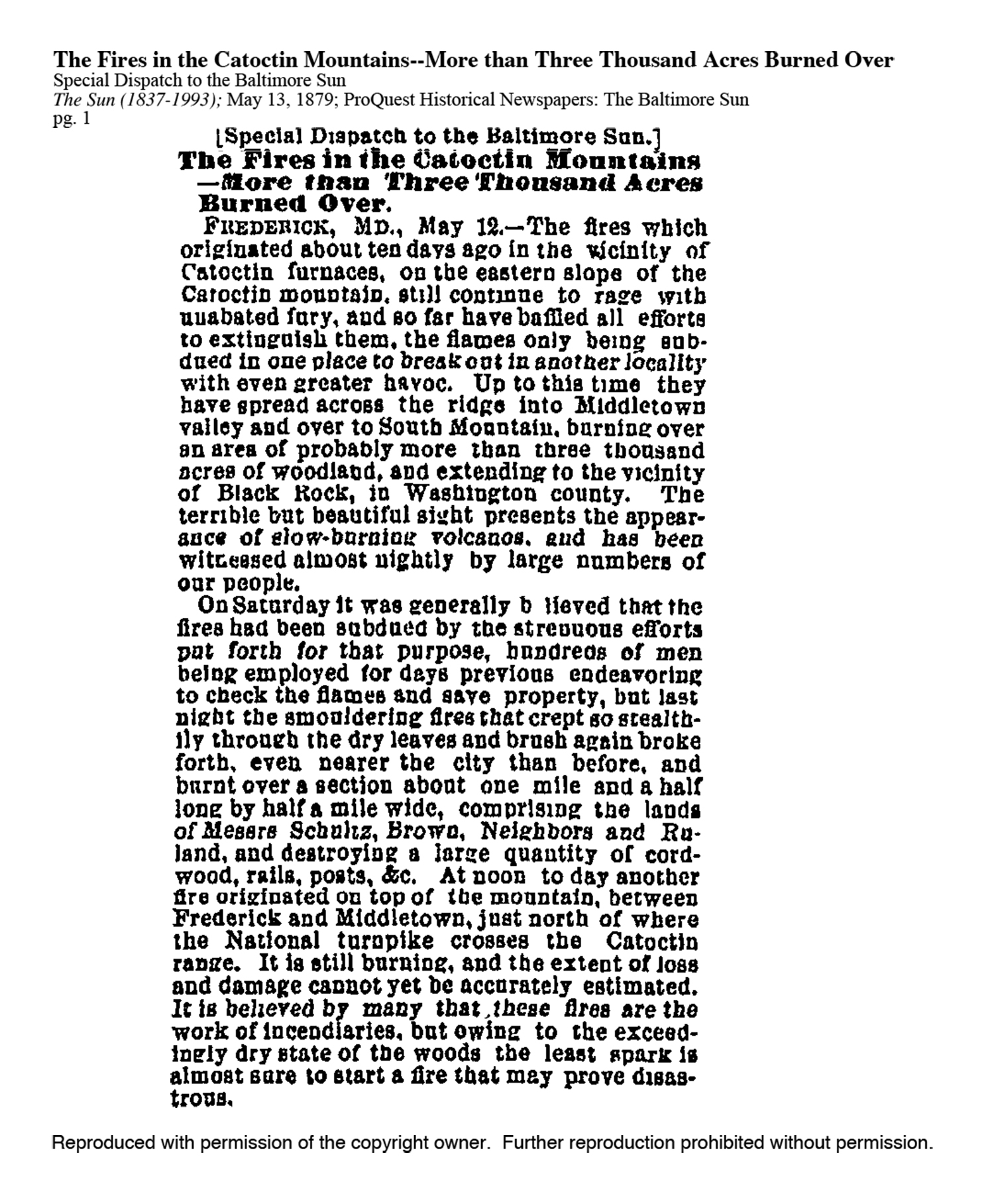

May 12, 1879

Catoctin Fires—This fire scar aligns with a May 12, 1879 Baltimore Sun article that dramatically describes the "unabated fury" of a more than 3,000-acre wildfire on Catoctin Mountain.

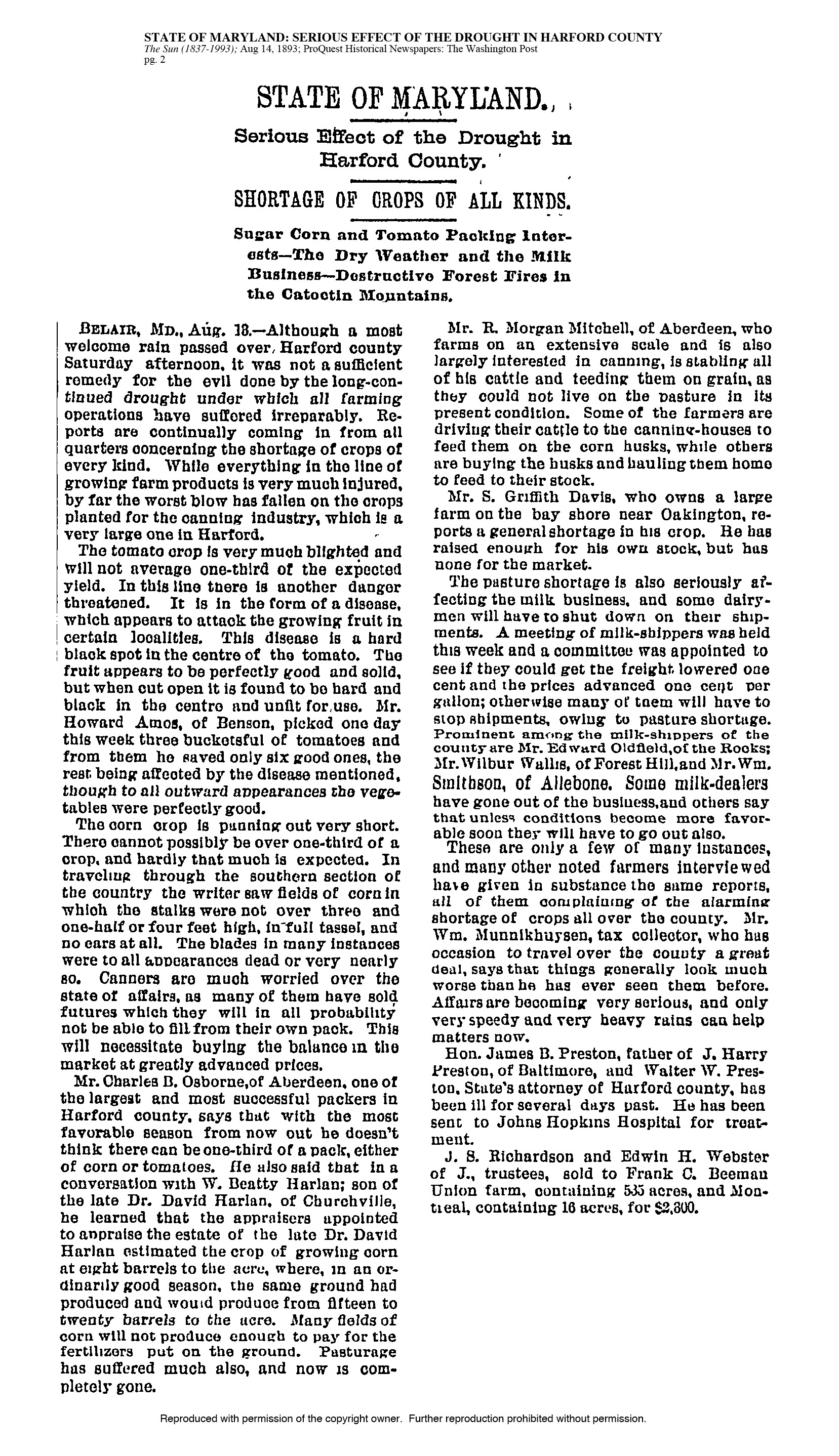

August 14, 1893

Severe Drought—This tree ring indicates a period of drought, aligning with an Aug. 14, 1893 Washington Post article that reported on the local effects being felt in Hartford County, Maryland, including food shortages and a fire on Catoctin Mountain.

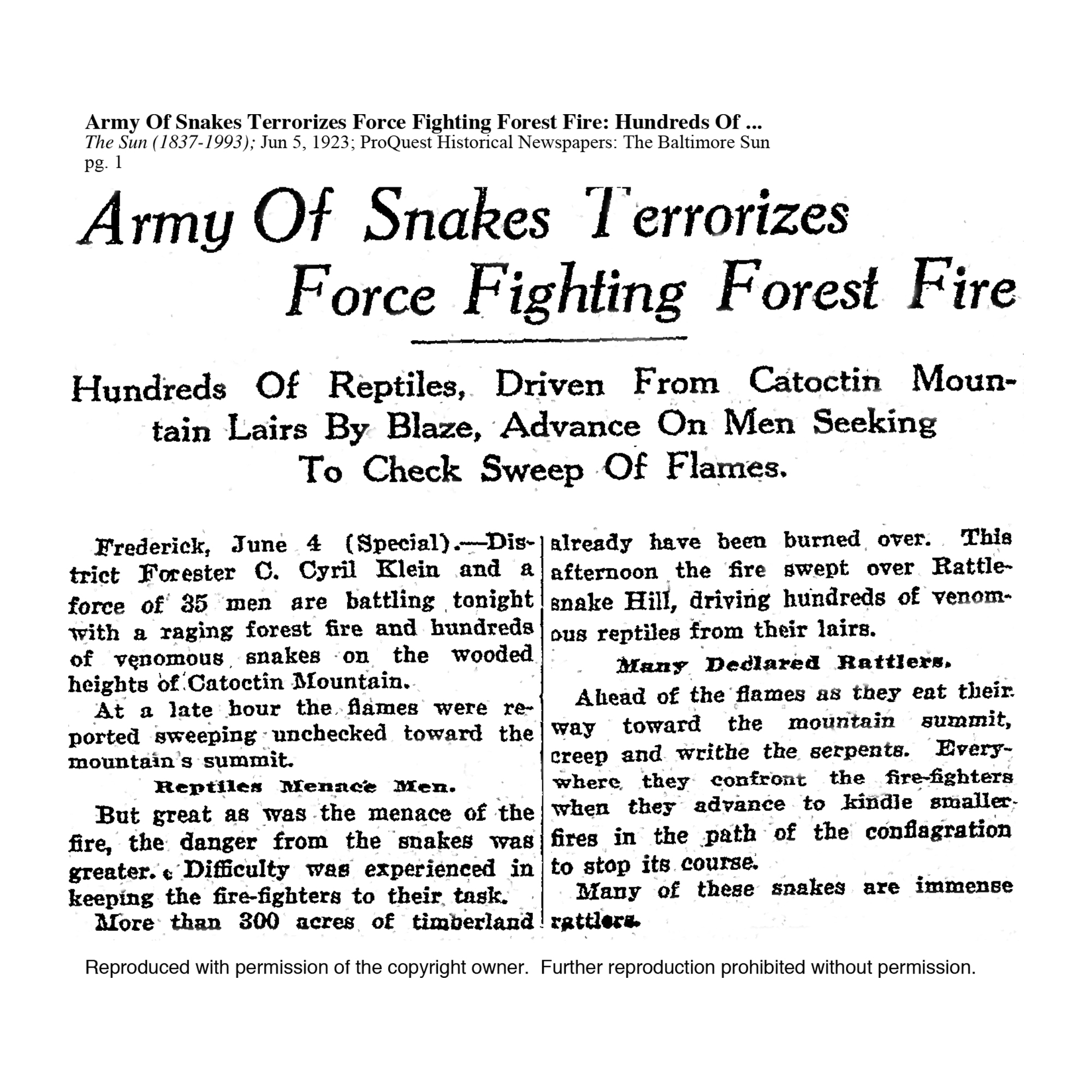

June 4, 1923

A Unique Challenge—this fire scar aligns with a June 4, 1923 Baltimore Sun article detailing the unusual conditions encountered while fighting a 300-acre fire on Catoctin Mountain.

While the trees can tell us when fires occurred, the historical record provides additional context—and in some cases, tells a story of intentional, human caused fire.

On May 17, 1923, the Catoctin Clarion reported on the efforts of the State Forestry Association to prevent what it described as "incendiary firing" of the forests on South and Catoctin Mountains. The article goes on to attribute these fires to berry pickers.

During the 1920s and 1930s, local residents set fires to encourage the growth of berry bushes, a means of eking out a living from the forest. Blueberries picked in the area were sold at the train station bound for markets in Baltimore and Philadelphia.

Planning for Change

Longleaf pine is a fire-adapted species, evolving naturally over many centuries as lightning strikes and Native American burning made fire a regular part of the landscape. It's also a species not normally seen in Maryland.

Southeast Virginia is the most northern range for longleaf habitat—but that may shift as a result of climate change. In 2013, TNC planted 1,000 longleaf seedlings over 20 acres at Maryland's Plum Creek Preserve. It's part of an experiment to look at whether assisted migration may be an option for the species.

As part of this pilot, TNC conducted a controlled burn at the site in 2020. Longleaf pine depends on fire to reveal bare mineral soil, stimulate seed germination and reduce competition from shrubs and faster-growing tree species.

As the environment in Maryland changes, it may become more similar to longleaf's historical range. And as animals that depend on longleaf pine are forced to migrate north, our hope is that they will find ready-made homes waiting for them.

Morning Chorus

Early morning forest sounds, including whippoorwill and Eastern towhee. Recorded May 21, 2019 at 5:14 am, Nassawango Creek.

No spoken words. 60 seconds of bird song, insects, and other natural sounds recorded at Nassawango Creek Preserve, May 2019.

The Sounds of Nature

Close your eyes and imagine the sounds of a forest—rustling leaves, a babbling stream, bird songs and a chorus of insects. There is a growing body of science dedicated to the study of nature soundscapes and how we interpret the sounds of nature.

For the past several years, MD/DC Conservation Steward Gabe Cahalan has been conducting an acoustic monitoring study on two TNC preserves in Maryland, comparing biodiversity in forests we have kept open with controlled burns to overgrown forests where fire has been suppressed by measuring the “bio-acoustic index” of each forest type.

In open forests where TNC has burned, we hear a higher diversity of birds and other species than in the overgrown forests. Gabe's study seems to confirm that our fire management is working and helping to preserve some of the rare species we aim to protect on our lands.

The science is clear that healthy, well-managed forests are good for people and nature. The global pandemic caused by COVID-19 has resulted in new and different levels of stress for all of humanity. It has emphasized the need to protect and conserve nature at a faster rate than ever before. Nature is talking to us, and we must listen.

Scaling Up the Maryland Fire Program

Controlled burns are always conducted with safety as the top priority. Burn staff are trained practitioners who monitor the weather leading up to and during a burn to ensure the fire remains at the desired intensity and smoke is carried up and away from roads and homes. If the required conditions for temperature, humidity, moisture levels, cloud cover and wind are not met or they unexpectedly change, the burn will be postponed.

Limited resources, including equipment and personnel, are often obstacles to implementing a successful fire program. In 2016 we led the expansion of the Central Appalachian Fire Learning Network (FLN), a collaboration between TNC and multiple state and federal agencies.

We have partnered with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service to conduct burns across nearly 2,000 acres of woods and wetlands on Maryland's Eastern Shore since 2007. Applying FLN's collaborative model successfully in western Maryland is a critical next step in keeping some of the state’s most valuable natural resources healthy and thriving.

By joining forces and pooling resources, we will dramatically scale up the size of our burns—and accelerate our progress toward the healthy forests of the future.

We Can’t Save Nature Without You

Sign up to receive monthly conservation news and updates from Maryland/DC. Get a preview of Maryland/DC's Nature News email.