Controlled Burn Longleaf pine forests need frequent low-intensity fires to increase forest health and improve habitat. © Margaret Fields

500k Acres of Good Fire!

In 2025 we reached a major milestone: 500,000 acres burned in The Nature Conservancy's history of working in North Carolina. This figure includes burns in TNC property and partner lands. TNC started burning in North Carolina in 1989 with three burns across 81 acres. We now burn at a pace of over 40,000 acres per year thanks to the hard work of many TNC fire leaders, strong partnerships, good science, a focus on training and development of fire staff, new models of operation, and securing funding for more crew, fleet vehicles and equipment.

Setting Good Fire

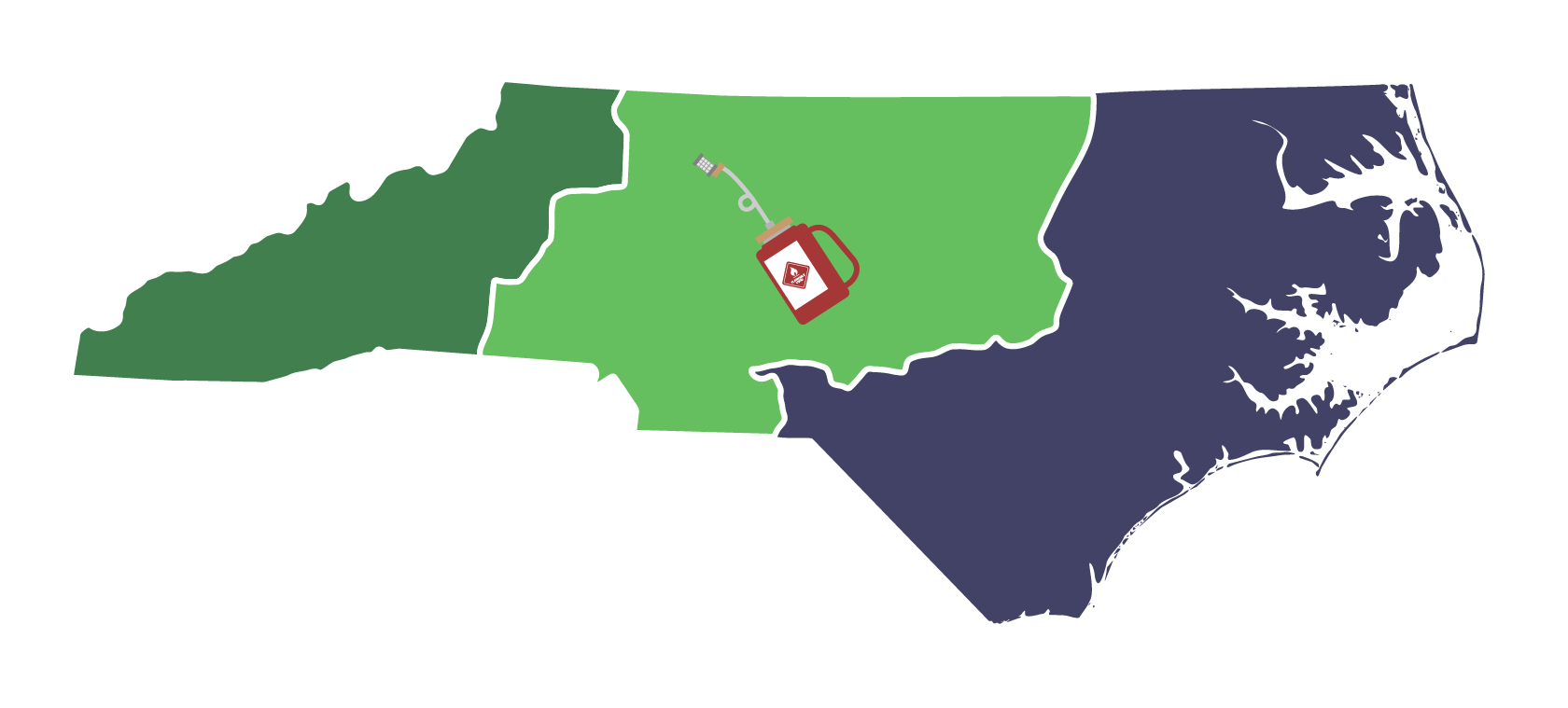

Our fire program extends throughout North Carolina.

Mountains

Launched in 2015, the fire program in the mountain region aims to restore native oak ecosystems and reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfires. Of the 500,000 acres burned, 25% were in this region.

Southeast

TNC's main focus in the Sandhills and Coastal Plain regions is managing longleaf pine habitat. Of the 500,000 acres burned, 75% were in this region.

How Did We Get There?

The 500,000th acre was burned on February 22 at Sumter National Forest in South Carolina. TNC’s Southern Blue Ridge burn crew will often assist on burns in South Carolina, Tennessee and Georgia. The strengths of the U.S. Forest Service partnership has allowed us to work across state lines and assist where forests need fire the most.

Benefits of Controlled Burning

Fire in the Sandhills and Southeast Coastal Plain

Fire is essential to maintaining the health of the longleaf pine ecosystem. Historically, longleaf pines were the dominant tree species across the southeastern United States coastal plain before European settlement. However, extensive logging in the 19th century drastically reduced their populations. These trees were vital to North Carolina’s naval stores industry, providing tar, pitch, wood and turpentine for shipbuilding—earning the state its nickname, the "Tar Heel State."

In the 20th century, public service campaigns against wildfires shifted public perception, often with unintended consequences for natural ecosystems. While Smokey Bear’s original message discouraged all fires, it has since evolved to distinguish between harmful wildfires and beneficial controlled burns, which are critical to forest ecology.

Today, The Nature Conservancy (TNC) is working to restore longleaf pine habitats on its lands using prescribed burns. These controlled fires prevent shrubby species from overtaking the landscape and shading out the understory, allowing sunlight to reach the forest floor and enabling the growth of wiregrass, wildflowers and young longleaf pines. Although longleaf pines are the longest-lived of the southern pines, their early “grass stage” can last up to seven years. During this time, they develop deep root systems that make them exceptionally resilient to drought stress.

Before and After

Longleaf forests are adapted to fire, and they bounce back after a burn healthier and stronger. The picture shows two burns done at Calloway Forest Preserve, a little less than one month apart. The objectives of the burns were to reduce fuel, restore native groundcover and improve habitat for threatened species, such as the red-cockaded woodpecker and Bachman’s sparrow.

One Month After a Burn

One Day After a Burn

This unit was burned on April 4, 2025, and the photo was taken the next day during the fire crew's regular monitoring after a controlled burn.

Be Part of This Work

Help us keep growing our fire program

Donate to North Carolina

Longleaf pines are considered foundational species, meaning they provide essential structure and habitat for a wide range of plants and animals. One iconic example is the Venus flytrap, along with many other carnivorous plants. The pine barrens tree frog, a species considered significantly rare in North Carolina, also depends on fire-managed habitats. These frogs breed in Carolina Bays, streamhead pocosins and Sandhill seeps—wetland environments that benefit from periodic burning. Fire helps control shrub density and prevents hardwood encroachment, preserving the frog’s breeding habitat. The pine barrens tree frog has been observed at TNC’s Calloway Forest Preserve, which is also home to other rare species, including the federally threatened red-cockaded woodpecker.

Fire in the Mountains

There is evidence that fire has played a role in the ecology of the Southern Blue Ridge for over 11,000 years. Early accounts describe how Indigenous peoples actively stewarded the land through the use of frequent fires, and scientists have identified fire scars recorded in tree rings and pine and oak charcoal buried deep underground. Much of the Appalachians’ oak-dominated forest was characterized as open and park-like with diverse and abundant flowers and grasses covering the ground—very different from how they appear today.

How to Manage Forests with Fire in the Southern Blue Ridge Resources

The damage left by industrial logging was followed by widespread devastating wildfires, that lead to the fire suppression policies in the early 1900s. Forest composition has changed and oaks have gone from making up 50% of southern Appalachian tree species to less than 25%. As oaks age and are at risk to forest pests and pathogens, shade-tolerant species such as maple and white pine block more than 95% of sunlight to the growth of the next generations of oaks and hickories. Restoring oak populations has become a priority because oaks make a more resilient forest ecosystem in the face of increasing extreme weather events. Compared to maples, oaks use water more conservatively and can stabilize steep slopes and resist erosion.

Like longleaf pines, oaks are a foundational genus. They provide essential food and cover, and habitat for many of the plants and animals found in western North Carolina’s forests. Species such as bobwhite quail, black bears, white-tailed deer and wild turkeys rely on oak-dominated forests with diverse groundcover that provides berries, seeds, insects and nest concealment. Pollinators also depend on these ecosystems. Research indicates that pollinator decline is partly due to fire suppression and the resulting reduction in floral diversity. Just like in a backyard pollinator garden, native plants need abundant sunlight to grow. Forests managed by controlled burning have many wildflowers such as Indian paintbrush, firepink and blazing star, supporting a vibrant and diverse pollinator community.

.jpg?crop=335%2C0%2C3328%2C2663&wid=300&hei=240&scl=11.095833333333333)