Wildfires mar peatland habitat When peatlands are degraded, wildfires further devastate the landscape. At the Great Dismal Swamp, wildfire events in 2008 and 2011 have scarred the refuge. © Sydney Bezanson/TNC

The Atlantic coastal plain along the eastern United States holds powerful potential in its peatlands. While these unique wetlands store carbon, preventing it from entering the atmosphere as a greenhouse gas, they also capture it. Restoring peatlands are proving to be a critical natural climate solution.

What are peatlands?

Peatlands are a type of wetland whose soils contain a high proportion of partially decayed organic matter, and they retain an incredible amount of carbon. Peatlands cover just 3% of the Earth’s surface but store more than twice the carbon as all the world’s forests. They span tropical rainforests, permafrost regions and coastal areas.

Due to its rich carbon content, peat is highly flammable when dried. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s 113,000-acre Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge is one of the sites for peatland restoration work. The refuge is a pocosin peatland. Pocosin peatlands are a type of peatland characterized by deep, acidic and sandy soils. They are found across the coastal plain in the southern United States. Centuries of ditching and draining have resulted in severely degraded peatlands. In both 2008 and 2011, the refuge experienced catastrophic wildfires that scorched the landscape. Today, the scar remains.

Peatland Restoration Tool

The American Carbon Registry (ACR) has approved a carbon offset methodology for the quantification, monitoring, reporting and verification of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reductions from the restoration of previously drained pocosin wetlands. Version 1.0 can be accessed here.

While burning peat releases massive amounts of carbon into the atmosphere, it also emits carbon constantly under normal circumstances through a process called volatilization. Restoring peat results in a carbon sink. TNC has developed a one-of-a-kind carbon methodology with TerraCarbon to quantify the emission reductions gained from restoring coastal peatlands in the southeastern United States. This tool is designed to help landowners generate and sell voluntary carbon credits via the American Carbon Registry that can help cover the upfront costs if they choose to rewet their own drained peatlands.

Eric Soderholm leads TNC’s work to restore peatlands in North Carolina, partnering with state and federal agencies to restore degraded peat soils by installing water control structures and other water management infrastructure throughout the refuge.

On his days at Great Dismal, Soderholm treks through the swamp to document ditch flow rates and water levels across the project site over time. This monitoring helps refuge staff understand hydrologic conditions and informs any need to adjust water control structure settings so that the project can maximize the habitat and flood resilience enhancements it provides.

Quote: Eric Soderholm

We are trying to mimic the natural hydrology of an intact peatland. These water control structures can be adjusted to reverse the impacts of drainage, allowing more water to be retained in the swamp.

Fighting Climate Change with Peatland Restoration

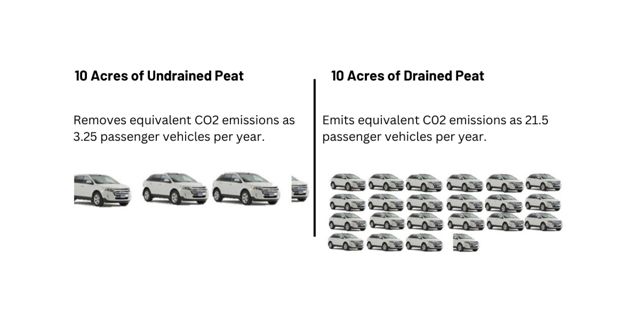

When re-saturated with water, peat soils are much less flammable, reducing wildfire risk. They also create conditions for more diverse and resilient forest communities to thrive. Since peat soils also have the great potential to sequester carbon, hydrologic restoration at peatland sites is a natural climate solution to climate change. Restoring 10 acres of pocosin peatlands is like removing 5.3 passenger vehicles per year, but draining 10 acres os like adding 21.5 passenger vehicles per year. Our work focuses on land protection, preventing drainage, and restoring peatlands.

Peatland Restoration Promotes Healthy Forests and Communities

Once the hydrology is restored, management interventions can be explored to help repopulate the site with peatland specialists, particularly Atlantic white cedar (Chamaecyparis thyoides). Cedar-dominated forests, which are now a globally threatened community, thrive in peaty, moist soil of swamps and bogs. Peatlands also support a variety of wildlife. Many neotropical songbirds, such as the prothonotary warbler (Protonotaria citrea), seek refuge in spring. In the summer, black bears (Ursus americanus) forage and enjoy the extra sun.

Human communities, too, benefit from the restored hydrology of peatlands. By fixing the drainage problem at these sites, TNC’s work is helping people downstream reduce their flood risk.

Flora and Fauna of Peatland Forests

In addition to sequestering carbon, peatlands are home to a wide variety of plant and animal species.

Black bear: The refuge is also home to animals like the American black bear (Ursus americanus). © Sydney Bezanson/TNC

Atlantic white cedar: Atlantic white cedar (Chamaecyparis thyoides) trees typically grow dense stands where peaty soils are saturated by groundwater. © Sydney Bezanson/TNC

Prothonotary Warbler: A Prothonotary Warbler forages at Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge. © Jeff Lewis

Carnivorous plants: Pocosin peatlands at the Green Swamp create ideal conditions for carnivorous plant species, including some unique hybrid varieties. © Skip Pudney

Looking Ahead to Expand Peatland Restoration

TNC has conducted peatland restoration at sites across the coastal plain, including at Pocosin Lakes, Alligator River National Wildlife Refuges, and Angola Bay Game Land (managed by Wildlife Resource Commission). These initial projects lay the groundwork for massive restoration to replicate beyond the state’s borders into the greater U.S. Southeast.

Our work will continue to grow with the recent $200 million grant from the EPA to advance nature-based solutions and reduce carbon emissions across Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia. This grant will help us restore 33,000 acres and protect 10,500 acres of peatlands in North Carolina and Virginia. This will result in significant reductions in carbon dioxide emissions. The minimum estimated annual reduction is equivalent to the emissions produced by 57,120 cars per year, while the maximum estimated annual reduction is equivalent to the emissions produced by 1.4 million vehicles per year.

Peatlands in Management

TNC is restoring peatlands across the U.S. Southeast with national, state, and local partners. In addition to providing incredible carbon benefits, restoration provides helps communities downstream recover more quickly from flooding events.

Great Dismal Swamp

Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge contains some of the most important wildlife habitat in the region. At close to 113,000 acres, it is also the largest intact remnant of a vast swamp that once covered more than one million acres.

Pocosin Lakes

Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge encompasses vast acres of natural wetlands, including the unique southeastern pocosin peat wetlands. It also is home to numerous species of migratory waterfowl.

Alligator River

The Nature Conservancy helped acquire the land to establish Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge in 1984. The refuge provides critical habitat for wildlife, including the red wolf.

Angola Bay Game Land

Angola Bay Game Land is managed by the North Carolina Wildlife Resource Commission. NC Wildlife is one of TNC’s newest partners in peatland restoration.

Green Swamp Preserve

The Nature Conservancy’s Green Swamp Preserve is a pocosin peatland and longleaf pine forest home to a variety of insectivorous plants, including the Venus flytrap.

Angola Bay Game Lands Update

TNC and the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission (WRC) worked with a team of hydrologic and environmental engineers to create a restoration design for 7500 acres of ditched pocosin in Angola Bay Game Land. The installation of water control infrastructure began in spring of 2023, with aims to complete efforts by the end of 2024. The second phase of this project involves restoring habitat. Along with our WRC partners, we plan to plant several hundred acres of former loblolly pine plantation with wetland species including the globally rare Atlantic white cedar, bald cypress, pond cypress, and buttonbush.

Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge Update

The US Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) has implemented hydrologic restoration across Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge (PLNWR) with partners since the 1990s. The refuge is broken into 5 Restoration Areas (Ras). RA1 covers over 17,000 acres. It was most recently expanded in 2016 with the addition of the 1,241-acre Clayton Blocks pocosin restoration project on the southern refuge boundary completed in partnership with TNC. RA2 is 9,400 acres, RA3 is 8,500 acres, and RA4 and 5 are 6,000 acres. The recently approved PLNWR Water Management Plan & Environmental Assessment outlines where additional restoration work is necessary to continue restoring or enhancing hydrologic conditions across the refuge.

Funding through the Inflation Reduction Act –the largest climate investment in history – allocated $27.25 million to the Service for restoration in the Albemarle-Pamlico Sounds region, which has been dedicated to addressing some of the outstanding needs at PLNWR. TNC is collaborating with USFWS and Kris Bass Engineering (KBE) to design and implement these recommendations in the water management plan. These restoration actions will build on the success of the previous collaborations at PLNWR and further improve the resiliency of its peatland ecosystem to fire, drought, and flood events. We will continue our successful collaboration with KBE to update restoration design recommendations for RAs 1, 2, 3, and 5 and implement necessary restoration actions in RA2. Then, to the extent practicable with the available budget, additional restoration actions in RA3, RA5, and RA1 may also be implemented.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

-

Europeans initially sought to drain peatlands along the coastal plain for human settlement. However, timber harvest later became a more profitable opportunity for enterprise. These wetlands as a result were ditched and drained for road construction and resource extraction. In addition, developmental pressures continue to loom for these special natural areas.

-

Peat is highly flammable when dried. When wildfires occur in degraded, dry areas, they have devastating impacts on the land, as they can continue to smolder for long periods of time. Historically, this has also made them a source of fuel for people.

-

Peat emits huge quanities of carbon dioxide when burned. Through carbon sequestration, 10 acres of natural, undrained pocosin peatland can remove 5.3 passenger vehicles’ emissions in a year. In contrast, 10 acres of drained peatland can add 21.5 passenger vehicles’ emissions.

-

Landowners can access the peatland restoration methodology through the American Carbon Registry.

Save Precious Peatlands

Your gift will help fund important work to fight climate change in North Carolina.

Give now