Restoring the Land of the Longleaf Pine

Fire helps the plants and animals of longleaf forests thrive.

.jpg?crop=0%2C231%2C4000%2C2200&wid=1300&hei=715&scl=3.076923076923077)

Longleaf pine was once the dominant Southeastern coastal plain tree, covering 90 million acres from southern Virginia to eastern Texas. North Carolina’s state toast describes the state as “the land of the longleaf pine,” but in the centuries after Europeans arrived, this tree was exploited to the point where just 3.5 million acres remained by the mid-20th century.

Longleaf pine is prized for its strong, straight wood and resistance to decay. These trees were used to create building materials and, during the Colonial period, ship masts. Its resin was an important source of tar, rosin, pitch and turpentine—collectively known as naval stores because of their use in shipbuilding. North Carolina was given the nickname of “the Tarheel State” around the time of the Civil War for its connection to this industry.

Longleaf pine forests are adapted to fire. In fact, fire helps young longleaf pines and native plants flourish by removing invasive shrubs and other competing vegetation. Indigenous people were forward-thinking environmental stewards, and for this reason, fire was an essential tool for maintaining healthy ecosystems on the coastal plain. However, in the 20th century, with the turpentine and logging industry booming, most fire was excluded from the forest to its detriment.

Today, The Nature Conservancy is working to restore, connect and manage longleaf pine, and longleaf ecosystems have rebounded to 5.2 million acres across the Southeast.

.jpg?crop=225%2C0%2C3549%2C2662&wid=512&hei=384&scl=6.932291666666667)

.jpg?crop=0%2C81%2C4000%2C2500&wid=640&hei=400&scl=6.25)

How Fire Works to Support Longleaf

Controlled burns, also known as prescribed fire, is the process of mimicking natural fire in the landscape. By managing the natural process of fire on the landscape, instead of preventing it, we can improve habitats for native plants and animals and reduce the risk of out-of-control wildfires.

Controlled burns require a lot of planning and only happen under the safest conditions by trained practitioners. Burn crews look at things like wind direction, humidity and the location of fire lines to determine when and where to burn.

Longleaf pine trees are specially adapted to fire coming through the landscape. The longleaf pine apical bud, located at the tip of the terminal stem, is crucial for the tree's growth and survival. As long as the bud remains intact, the tree will survive.

Longleaf Pine Growth Stages

In the "grass stage,” which can last up to seven years, seedlings grow strong root systems while keeping the bud at ground level, away from the hottest part of a fire. In this stage, fire is crucial to keep the forest floor clear from brush and other species that can grow quickly and outcompete the young longleaf.

In the bottlebrush and sapling stages, dense needles protect the bud from fire’s heat. A strong root system allows saplings to quickly grow above a typical fire’s flame height. Mature longleaf pine trees have thick, protective bark and, while they may lose most needles after a fire, the needles immediately regrow, and the trees are soon bushy and green again.

Get Updates from the Field

Sign up for our monthly e-newsletter.

First Longleaf Pine Stewards

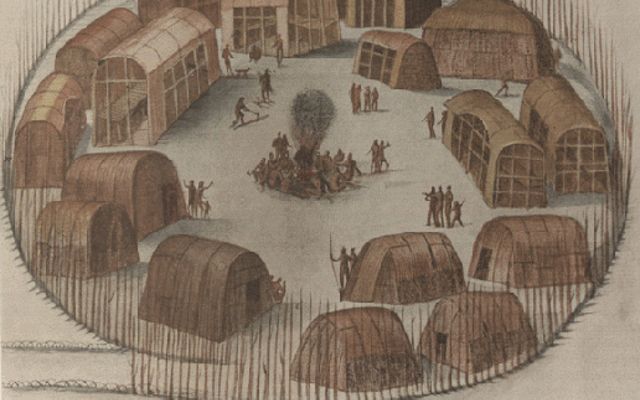

The history of the Lumbee and Waccamaw Siouan tribes are deeply woven into the pine needles and deep root systems that characterize longleaf pine trees. In 1526, Spanish explorer Fernández de Oviedo wrote about Waccamaw Siouan ancestors’ houses made out of longleaf pine:

Quote: Fernández de Oviedo

All along the coastline of this region were large principal houses constructed of tall pines. The crowns of the pines were bent over and intertwined with branches to form a roof...These handsomely built square dwellings easily accommodated over 200 people comfortably.

Windy is a historian and conservationist of Waccamaw Siouan descent from Castle Hayne, NC. Windy's work is rooted in the belief that history and environmentalism are inextricably linked. With deep family ties to the Waccamaw Siouan Buckhead community, she approaches conservation through the vital lens of Indigenous land practices. This perspective guides her role as the Education and Marketing Coordinator for the Hooheh Cultural Burn project and in her other work. Now serving on the NPCA’s Next Generation Advisory Council and pursuing a degree in Fisheries and Wildlife Conservation at Oregon State University, Windy continues to advocate for a future where history illuminates our path and conservation guides our steps forward.

Windy Daniels, Waccamaw Siouan STEM Program Education and Marketing Manager, explains that these structures were large meeting houses where clans gathered. At the center of the house was the sacred fire, with an opening in the ceiling to allow smoke to escape. The name of these principal houses is ouke, pronounced “Oh-u-k,” the Woccon word for house. Woccon was a subdivision of the Waccamaw and likely spoke the same or a similar Siouan language as the Waccamaw Siouan today.

The turpentine and logging industries of the 1800s devastated longleaf pine forests, deeply affecting the tribes that called them home. Communities lost ancestral lands, ceremonial traditions and the ability to pass down cultural knowledge across generations. One of those ancestral areas was the Green Swamp region in southeastern North Carolina—a vast wetland system full of longleaf pine and cypress trees that served as refuge and home for the Waccamaw after the Tuscarora Wars.

In the early 1900s, the Waccamaw Lumber Company began large-scale logging in the Green Swamp. They acquired over 230,000 acres across Columbus and Brunswick counties and constructed an 18-mile railroad into the swamp, which they drained to harvest the timber. “The environmental and cultural disruption was profound. But the most damaging effect we’re still dealing with from those industrial activities is the health and environmental concerns. We’ve faced challenges with soil and water contamination, which has led to increased health risks—especially elevated cancer rates,” Windy reflects.

A walk through TNC’s Green Swamp Preserve offers a glimpse into what the region looked like before European arrival. It remains one of the best existing examples of healthy longleaf pine savannas interspersed with pocosin wetlands.

About Windy Daniels

Windy is a historian and conservationist of Waccamaw Siouan descent from Castle Hayne, NC. Windy's work is rooted in the belief that history and environmentalism are inextricably linked. With deep family ties to the Waccamaw Siouan Buckhead community, she approaches conservation through the vital lens of Indigenous land practices. This perspective guides her role as the Education and Marketing Coordinator for the Hooheh Cultural Burn project and in her other work. Now serving on the NPCA’s Next Generation Advisory Council and pursuing a degree in Fisheries and Wildlife Conservation at Oregon State University, Windy continues to advocate for a future where history illuminates our path and conservation guides our steps forward.

Healing the Land While Healing Each Other

“Hooheh” is the Woccon word for longleaf pine, and “Yau” means fire. The Hooheh Restoration Cultural Burn Program, funded by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and TNC, is reintroducing traditional fire management practices to tribal communities, restoring longleaf pine ecosystems, developing educational programs for kids and fostering opportunities for the Waccamaw Siouan Tribe to engage in decision-making, economic development and co-management of ancestral land.

On February 2025, as part of the longleaf restoration, the Waccamaw Siouan Tribe hosted a tree planting ceremony on their tribal grounds in southern Bladen County. “It was the first time our people have come together for something like that, ever,” Windy shares.

Quote: Windy Daniels

We had representation from all of the original families, and it was an amazing day of celebration and community. And I’m not sure what it was, but you could just feel the ancestors there with us that day.

TNC’s Plant a Billion campaign helped prepare the site and plant 18 acres of longleaf. The ceremony highlighted the work of the Hooheh initiative, including a ceremonial planting of trees in a circular pattern, which will eventually bend and form an ouke”—a traditional home. Each tree represented one of the main families of the Tribe and was planted by an Elder from that family.

“We know they won't be there to see that, but by having them plant those trees, it is a continuation of their spirit and love growing with us forever,” Windy says. “This was a powerful and emotional connection that further tied us to the land and our people.”

Plants and Animals that Inhabit Longleaf Pine Forests

Longleaf pines are considered a foundational species: they provide essential structure and habitat for a wide range of plants and animals. You can see and hear all these species at our Calloway or Green Swamp preserves.

Essentials for Longleaf Pine Forest Owners

North Carolina offers a robust network of support for landowners managing longleaf pine forests. These resources include technical guidance, financial assistance and conservation partnerships:

Prescribed Burn Associations: A community-based organization connecting private landowners and interested citizens to a prescribed fire network. Offers cost-share programs and technical assistance.

Safe Harbor Program: Started in 2006 with goal of recovering the population of Red-cockaded woodpeckers, while providing assistance to private owners. Offers management guidance, pest control and flexibility to continue timber production, and reduces legal uncertainty from having an RCW on your land.

Statewide Safe Harbor

Sandhills Safe Harbor

Land protection: TNC acquires land in strategic locations to meet longleaf conservation goals. Purchased lands are often transferred to state or federal agencies to allow for public use and enjoyment, while other properties are added to our network of nature preserves. TNC will also acquire conservation easements, where the landowner retains ownership of the property and sells or donates the development rights and other land use rights that would degrade the conservation values. TNC works in partnership with the landowner to protect the habitat on the property. To date, TNC has contributed to the protection of over 740,000 acres in North Carolina.

The Longleaf Alliance: Provides educational materials and restoration strategies, and connects landowners with local implementation teams.