Sustainable Rivers of North Carolina

Managing water flows on the Cape Fear and Roanoke Rivers for the benefits they provide to nature and people.

The Nature Conservancy in North Carolina has created a source-to-sea water program with a holistic conservation approach. We work across the state with four strategies: managing flows, barrier removal, healthy functioning floodplains and wetlands—which includes peatland restoration—and, lastly, forest-to-water, which is how water flow impacts land management.

The basis of our program is managing flows because rivers were meant to ebb and flow. Nature depends on that rhythm. Bald cypress trees need a wet-dry cycle to germinate. Fish need pulses of water to cue them to swim upstream and spawn. Mess with the rhythm of nature and the cascade of negative consequences are countless.

Just 2% of the nation’s three million miles of waterways are undeveloped and free flowing. Rivers were dammed for water supplies, flood control, navigation and hydropower—altering the course of nature. The Nature Conservancy has partnered with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) , the country’s largest water manager, to create the Sustainable Rivers Program (SRP). In North Carolina, that work is taking place on the Cape Fear and Roanoke rivers, both are home to large dams owned and operated by the USACE. Those dams aren’t going away, but they can be managed in a way that benefits nature, which we are part of.

Ashley Hatchell, who works in water management out of the Corps' Wilmington office, says the SRP fits perfectly into the Corps’ mission. “The Corps has the responsibility of helping care for our nation’s rivers, lakes, and wetlands. This responsibility goes beyond the narrow focus of flood control and hydropower that many people perceive as our primary mission,” she says.

Managing Dam Releases to Improve Water Quality and Fish Spawning at the Cape Fear River

Julie DeMeester, TNC NC Water Program Director, has a daily routine. Every morning, she wakes up and looks at the United States Geological Survey (USGS) gauges that monitor water flow on the Cape Fear and other rivers. Julie and her family live in Durham, so they drink from the Cape Fear when they turn on their water tap.

The Cape Fear is the state’s largest water basin; more than 2 million people live there, accounting for more than a fifth of the state’s population. B. Everett Jordan Dam sits in the upper basin, 200 miles from the Atlantic. Jordan Lake also provides drinking water for fast-growing Triangle communities, including Cary, Apex, and Morrisville.

The Nature Conservancy and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers use a collaborative science-based approach to understand how we can better manage reservoir releases to improve fish passage and water quality, explains Hatchell.

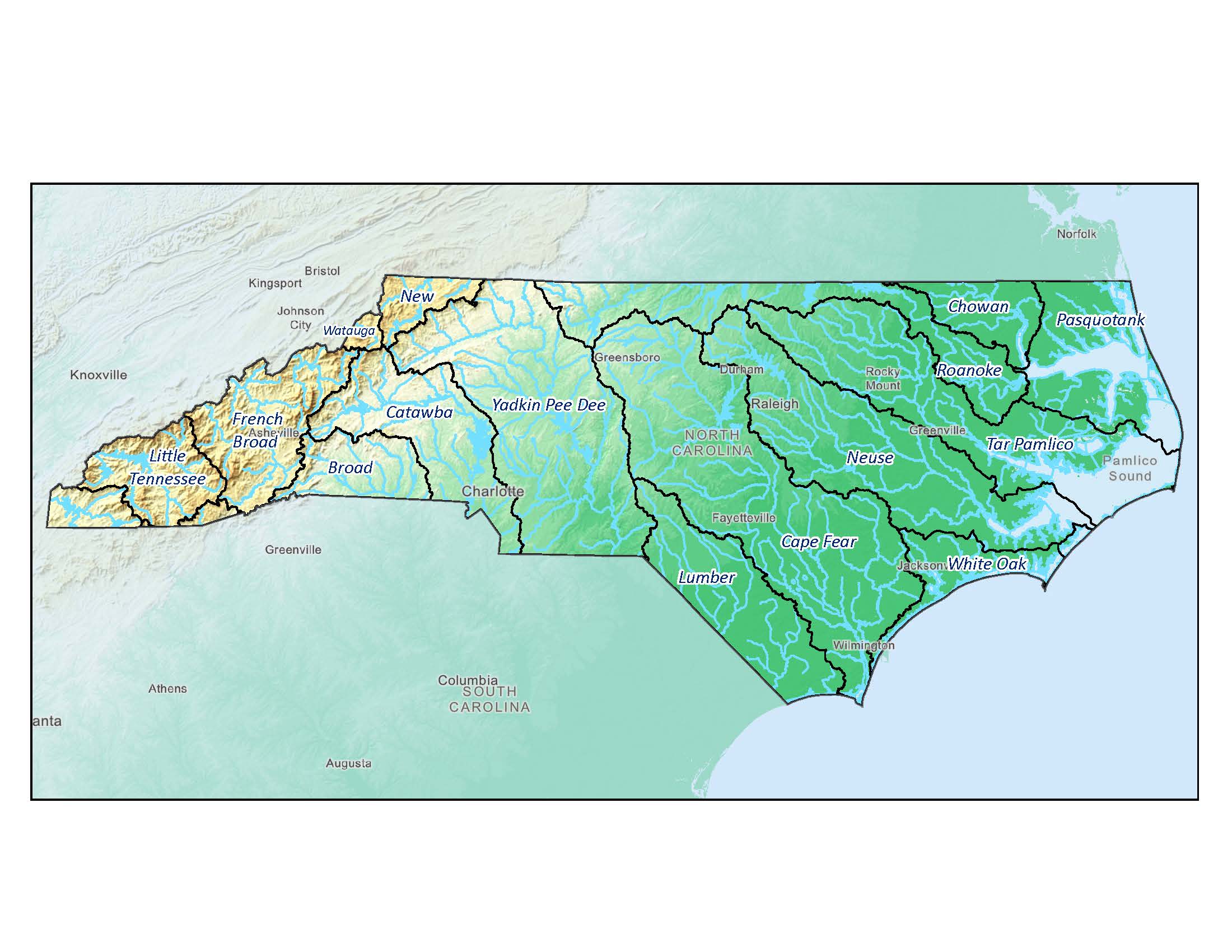

Water Sources in North Carolina

In North Carolina, our drinking water comes from both ground and surface sources. Click through the map to learn where your drinking water comes from.

Raleigh

The Neuse River provides drinking water to Raleigh and Durham.

Durham

The Neuse River and the Cape Fear River provide drinking water to Durham.

Wilmington

The Cape Fear River provides drinking water for Durham, Chapel Hill, Fayetteville, and Wilmington.

Asheville

The French Broad River provides drinking water for Asheville.

Charlotte

Catawba River provides drinking water to Charlotte.

During hot, dry months, water on the Lower Cape Fear stagnates, resulting in blue-green algae blooms, which can be harmful to people and animals. Releasing water from Jordan Lake can stir up that water and disrupt the algae blooms. We work on creating a model that gives a better picture of water quality in the Cape Fear River basin. Rhonda Locklear, Environmental Program Manager with the Fayetteville Public Works Commission, has seen benefits from this project because it translates into cost savings. Water treatment for nutrient removal is expensive, and improving water quality is a big benefit for all water consumers.

In spring, anadromous fish, which live mostly in the ocean but come upriver to spawn, get stuck on the river's lower reaches, which are blocked by a series of locks and dams managed by USACE. These fish—shad, herring, striped bass, and sturgeon—can make their way past the locks and dams if there is enough water flow. Timing releases from Jordan for when the fish need to swim upstream can help them make it to the rocky parts of the river further upstream, where they like to lay their eggs. That’s why DeMeester wakes up and checks the water gauges first thing—to see if it is a good day to release water from Jordan Lake. “I watch that river every day,” DeMeester says.

Restoring the Roanoke River Floodplains

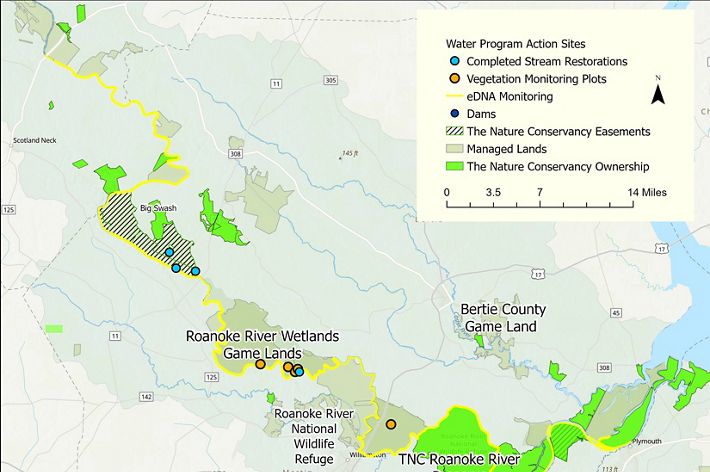

TNC has protected over 95,000 acres along the Roanoke, which is also part of the Sustainable Rivers Program. We work on improving water releases from dams, mimicking natural flow patterns to help fish spawning and water quality and restoring floodplains that have been altered by humans. We’re using cutting-edge tools to measure restoration effectiveness and lead the research on how to make dam operation decisions through a climate change lens.

Jean Richter, a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, who has worked on the Roanoke River National Wildlife Refuge since 1996 is concerned about the change in rain patterns. She is seeing a lot of dead trees because the rain is coming earlier and lasting longer—the climate research will give the USACE, TNC and her organization data to address the issue.

A big part of floodplain restoration and fish spawning is correcting the hydrology altered by road crossings and undersized culverts that hold floodwaters and trap fish. Aaron McCall, TNC NC land steward, is leading this work, replacing the culverts under the roads with fish-friendly bridges, which allow floodwaters to rise and fall. Instead of being trapped and killed, the fish can continue upstream to spawn as they have been doing for millennia.

Restoring the flood plain requires intense effort and resources, so we want to ensure it is worth the effort. McCall and TNC Fellow Chase Spicer monitor to see if the restoration is working. They use a combination of sampling tools pre and post-restoration, such as eDNA, fish traps and electrofishing, to detect whether a particular species of fish has passed through the water. You can learn more about this work in our 'Identifying fish species' article.’ Thanks to this research, we know that anadromous fish such as blueback herring and shad, which usually live at sea but come upriver to lay their eggs, are using the now barrier-free waterways.

There is still a lot of work to be done! There are many more barriers along the 140-mile floodplain from the Atlantic to the first dam on the Roanoke, and we are prioritizing critical areas for restoration.

Join this Mission

Create an everlasting impact.

Donate to North Carolina

Anadromous Fishes at the Roanoke and Cape Fear

Anadromous Fish are hatched in freshwater. The juvenile fish head out to sea, where they spend much of their adult lives, but return to freshwater to spawn. Removing manmade barriers, so that they can move upstream to spawn, is key to TNC’s river work. © NCFishes | The Atlantic Sturgeon image was taken under the authority of NMFS ESA Permit No. 21198

-

American Shad

American shad, also known as white shad, is the largest shad species. Females average 24.3 inches and males 19.7 inches. Their numbers declined over much of the 20th century due to overfishing and habitat degradation in their spawning areas.

-

Atlantic Sturgeon

Atlantic sturgeon are protected under the Endangered Species Act. Sturgeon mature and grow slowly. Males take a decade to reach sexual maturity—females twice as long. They are the largest fish in North Carolina freshwaters, weighing up to 800 pounds.

-

Blueback Herring

Blueback herring, also known as river herring, reach a maximum of 16 inches and live for 8 years. Because of their reduced numbers, there is a moratorium on harvesting blueback herring in North Carolina.

-

Striped Bass

Striped bass, also known as rockfish, start spawning when they are 2 to 4 years old. Although stripers are found in several North Carolina river basins, the Roanoke River is home to the state’s only wild population of stripers.