Red-cockaded Woodpecker Wars

Learn how an endangered bird brought together conservationist and the army.

The recovery of the red-cockaded woodpecker (RCW) in the Sandhills is one of North Carolina's major success stories, not only because this tiny bird is thriving but because of the nationwide impact that this protection project has today.

Why is the red-cockaded woodpecker so important?

“Management for red-cockaded woodpecker habitat is also good management for a wide suite of plants and animals,” explains Jeff Marcus, TNC longleaf pine applied scientist. RCWs are picky when it comes to housing. They seek out longleaf pines whose dense heartwood has been softened by a fungus called red heart disease. Only mature pines over 80 years old are affected by red hearts. They are also cooperative breeders; young birds from previous generations remain with their parents. “Red-cockaded woodpecker cavities are a limiting resource on the landscape, and they need a large area to forage for insects,” explains Marcus. “Up to 200 acres will be used by one family. There is only so much space.”

This is why the management of RCWs revolves around longleaf pine—acquiring longleaf pine forests and improving them through controlled burning. These forests need fire to thrive. Fire clears their floors and makes room for new longleaf growth. Wiregrass, wildflowers, animals and iconic plants such as carnivorous plants are all part of the longleaf pine habitat. Working to protect RCWs is important because their management benefits the whole forest.

The Woodpecker Wars

When the Endangered Species Act passed in 1973, RCWs were the first bird protected. These species had a rapid decline in their population due to the loss of their preferred nesting tree—longleaf pine trees have been reduced from 90 million acres to just 3.2 million.

Fort Liberty (formerly known as Fort Bragg) is one of the biggest army installations in the world by population—it is also home to pristine longleaf forest and to RCWs. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service issued a Jeopardy Biological Opinion in 1990, requiring the Army to recover the local population of the federally endangered bird at Fort Liberty. So, the woodpecker wars began! The army was restricted in its operations and local landowners were cutting down longleaf pine to prevent birds from nesting. “The red-cockaded woodpecker was an evil spirit and the people who were trying to save it were also evil,” remembers Tim White, former editor of the Fayetteville Observer.

This issue was growing and growing with time; the Army was considering going to Congress for an exemption to the Endangered Species Act. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), The Nature Conservancy and the Army sat down to find common ground and a solution to this issue. Even though the first meetings required many “cooling off” breaks, the constant communication, listening and trying to understand each other’s work, finally paid off.

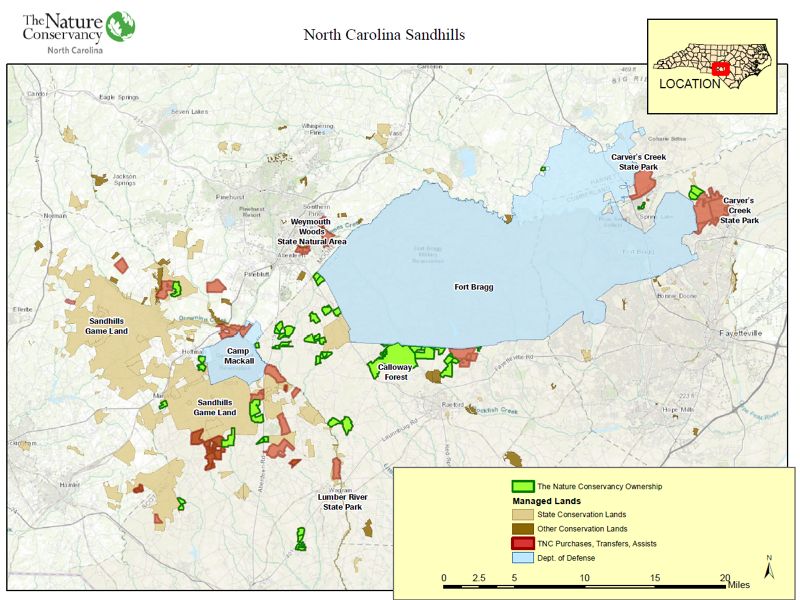

The first program that emerged from this partnership is called the Readiness and Environmental Protection Integration (REPI), which allowed the army to fund protection off base in the surrounding region. When a woodpecker leaves its nest, it generally flies short distances from tree to tree. They have difficulty crossing a treeless area of more than about 200 meters. Hence, there is a need to create corridors of forest for them to move from spot to spot. That’s why TNC identified important properties that would create these corridors and fill in the gaps between the eastern population of woodpeckers at Fort Liberty and the western population at Camp Mackall (another Army training facility) and Sandhills Game Land. Once these properties were identified, with the help of the Army and USFWS, we purchased the land and protected it.

Another important program that came out of this partnership is the Safe Harbor program, which allows non-federal property owners to enter into a voluntary agreement with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to protect a species listed under the Endangered Species Act. These agreements remove uncertainty for landowners who are trying to manage their land in a way that attracts endangered or threatened plants and animals. Property owners don’t have to worry that by attracting these animals and plants to their land they may face additional land use restrictions down the road. If their land management unintentionally kills or harms a protected species, they will not face legal action. The landowner may choose to return the property to its original condition when the agreement expires. “Safe Harbor is designed to build trust for landowners and give them security. It is a mechanism to assuage fears and concerns,” says Jeff Marcus.

The local population of RCWs at Fort Liberty was declared recovered in 2005—six years before the deadline set by USFWS, but the partnership didn’t stop there. Conservation and protection became part of the Army’s mission and this model that started in the Sandhills in NC has been replicated across the country. Longleaf pine across the southeast U.S. has grown to 5.2 million acres driven in part by this partnership. RCWs numbered less than 10,000 individuals in the mid-1990s, and today, there are between 18,000 and 19,000 individuals today.

Marcus says one of the main factors in accomplishing conservation success has been the trust that has grown between the community, the local governments, the military, The Nature Conservancy and other conservation partners. Everyone came to the table with good intent and listened to each other. “The success of the red-cockaded woodpecker recovery in the Sandhills showed the public that we can work together to solve difficult conservation challenges. Instead of fighting, we can work together to meet the needs of the species and the interests of landowners.”

Nature Right to your Inbox

Sign up to receive monthly conservation news and updates from North Carolina. Get a preview of North Carolina's Nature News email.