In Need of Fire

Oregon’s dry forests are missing a lot of wildfire—and that’s not a good thing.

Oregonians are extremely concerned with wildfires and their impacts – risk to life and homes; harm to the health of our forests, watersheds and wildlife habitats; and negative economic implications for businesses. After a century of fire suppression left our dry forests wildly out of balance, and with climate change only making things worse, significant policy reform and increased investment were needed to change the trajectory.

After years of study and collaborative discussion, Oregon is taking a forward-looking, comprehensive approach to improve community preparedness and reduce wildfire risk, helping our communities adapt to and heal after inevitable wildfire events. Now the state must ensure this strong trajectory continues while achieving ecological restoration in strategic, high-priority dry forests and rangeland landscapes.

Over the past century, forest managers have reacted to wildfires by putting them out as quickly as possible. While this is necessary whenever there is a threat to a community, suppressing all wildfires has had an unintended effect on Oregon's dry forests: small trees and overgrowth have accumulated on the forest floor and are causing more severe and destructive wildfires.

In Oregon, the dry forests in the eastern and southern parts of the state have adapted since time immemorial to frequent, low-intensity wildfires that either occured naturally or were used by Indigenous Peoples to manage the landscape. Regular burning not only serves to clear out small trees and brush that acts as fuel but it also enhances wildlife habitat and plant life. In other words, low-intensity fire plays many important roles in dry forests. But as a fire grows in severity, so does the damage to big trees and the forest itself.

A recent study by scientists from The Nature Conservancy, the US Forest Service, and the University of Idaho shows that dry forests in Oregon and Washington are experiencing far less low-to-moderate severity wildfire than they did 100 years ago. And that's causing problems. The study, The missing fire: quantifying human exclusion of wildfire in Pacific Northwest forests, USA, demonstrates that low-severity wildfire historically played a huge role in the ecology of these dry forests and that we are experiencing more high-severity fires in its absence.

Low-severity fire is defined as a fire in which less than 25% of trees are killed, while 75% of trees are killed in a high-severity fire. While low-severity fires restore resilience in forests, more severe fires change the makeup of the forests such as transitioning from forest to shrublands and grasslands. High-severity fires also pose increased risk to communities and firefighters.

“Within the areas that have burned over the past three decades, we saw proportionally more high-severity fire and much less low-severity fire in our dry forests,” said Ryan Haugo, Director of Conservation Science for The Nature Conservancy in Oregon. “This is another indication that we need to step up our efforts to bring low-severity fires into the forest using tools like controlled burning to reduce the fuels that feed the high-severity fires.

What Does This Mean for Our Forests?

The study has implications for current and future management of these forests. In a nutshell, said lead author Ryan Haugo, we need much greater use of prescribed fire as well as managed wildfire to restore balance to Oregon and Washington’s dry forests and keep communities safer

Quote: Ryan Haugo

There is no future without fire. We need to step up our efforts to bring low-severity fire back into dry forests with controlled burning.

Different Forests Need Different Solutions

In dry forests, a combination of controlled burns and ecological thinning are proven methods restore the ecosystem and reduce wildfire risk to communities. However, the state's wet forests west of the Cascades require a different approach. As we saw in 2020, fires here occur when dry conditions and extreme weather align and can have devasting impacts on communities.

Our Forests Need More Controlled Burning

The study is not advocating for a return to historic levels of burning, as there would be impacts on people and communities. The solution is better forest management including using prescribed or controlled burns to move towards historic levels of low-severity fire.

“We need to take advantage of this window of opportunity while it exists,” says Haugo. “Prescribed or controlled fire, managed wildfires, and mechanical treatments such as ecological thinning are all methods to restore dry forests to more natural conditions, which would make the dry forests of the Pacific Northwest more resilient as we deal with climate change and worsening summer droughts.”

What Happens in a Forest Without Fire?

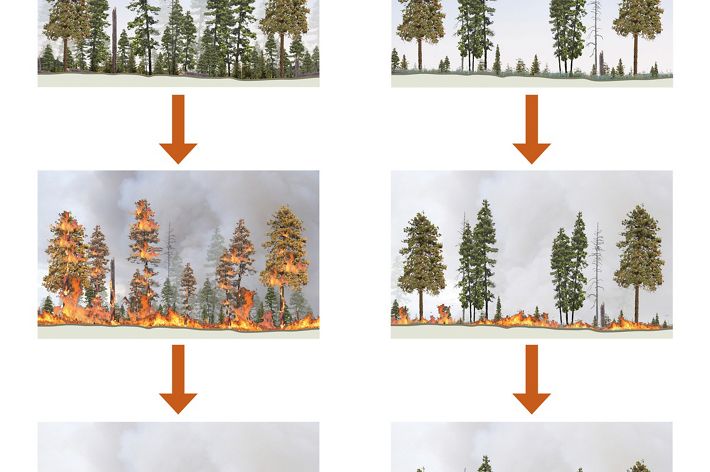

In a western dry forest that has been denied the benefits of fire, large and small trees grow in close proximity. Vegetation and other debris are crowded on the forest floor and becomes fuel for wildfires.

Because of this fuel, wildfires burn much hotter and are able to move from the ground up into the tree and consume it. This causes historically resilient trees to die. It will take decades of regrowth to see the large trees become valuable to wildlife and carbon storage again. The intense heat from the fire also changed the soil, making it more likely to erode into streams.

What About an Ecologicially Managed Forest?

Controlled burning, paired with ecological thinning, results in forests with minimal vegetation and growth on the forest floor, leaving less fuel for wildfires. This forest has adequate space between large trees that prevents wildfire from moving from the ground to the tree canopy.

After a wildifre, the majority of trees are scarred at their trunks, but remain alive. The ground is covered with a mix of soil and ash, with a few snags for wildlife. This forest can regrow and withstand future wildfires, thus holding on to its carbon capture and ecological benefits. Future wildfires can also be safely managed if they threaten human communities.

Different Forests Need Different Solutions

There are vast ecological differences between the wet forests in western Oregon and the dry forests in the east and southwest parts of the state. The state’s dry forests thrive with frequent, low-intensity fires that burn every 3-30 years and maintain plants, habitats and an open forest floor. Here, the combination of ecological thinning and controlled burns are proven methods to restore the ecosystem and reduce wildfire risk to communities.

In the fall of 2020, however, we saw something different; tragic wildfires in our wet forests. These forests historically burn much less frequently, and are more likely to burn intensely when they do. Fires here occur when drought, dry conditions and extreme weather align as we witnessed this past September. The complexities of this ecosystem require a different approach. As state and local leaders wrestle with potential solutions, The Nature Conservancy brings the scientific expertise needed to protect our communities and keep our forests healthy and resilient.

Join Us

Stay informed. Together, we can restore our forests and reduce the risk of severe fire.