Secrets of the Seagrass

A spontaneous snorkeling experience in Narragansett inspired Ocean State: Rhode Island's Wild Coast, a new marine science docuseries for PBS.

By Tomas Koeck, Guest Blogger and Filmmaker

Whenever I introduce the prospect of doing a film series on the smallest state in the U.S., I always get the same question: “Why Rhode Island?” Growing up in Connecticut, tiny Rhode Island was always a stone’s throw away, yet I spent very little time there and had no idea what types of habitats the “Ocean State” hosted.

In my mind, New England's oceanic environments were characterized by mudflats, murky waters and silty-bottomed beaches. I thought underwater activities like snorkeling and scuba diving were limited to the tropics; surely New England's relatively poor water clarity didn’t allow one to explore its underwater worlds. I had no idea how wrong I was until one fateful trip to Rhode Island, one that would pave the way for the series I am working on now, Ocean State: Rhode Island’s Wild Coast airing this January on Ocean State Media (WSBE) and streaming on the PBS Passport app.

Snorkeling in Narragansett

In 2018, my family and I visited my Rhode Island cousins. The plan was simple and relaxed: we would rent kayaks and paddle downstream on the Pettasquamcut River to Narragansett Beach, set up our umbrellas, hang out on the beach, and enjoy the day until sunset. We arrived at the mouth of the river by noon, just in time for lunch, where we met up with my aunt, uncle and cousin Dave. I was getting ready to boogie board and catch a few waves when I saw Dave pull out a pair of fins.

“Want to go on a quick snorkel run?” he asked.

I was confused. Snorkeling in Rhode Island? Surely this was just for the sake of it and not with the intention of actually seeing anything. Nonetheless, I agreed, borrowing a mask, snorkel and fins. Upon jumping into the water, I entered an experience that would stay with me forever…

Get Involved with Nature

Sign up for the latest conservation news and updates on how you can help us protect our natural world.

Guadalupe Island to Rhode Island

Beneath the surface of the ocean, I discovered what I would later learn was a quintessential New England inshore environment. Schools of striped bass swam past me, a flounder was flushed from a sandy patch beneath me, and tautog patrolled among the rocks, hunting for shellfish. Small patches of eelgrass swayed back and forth in the waves. I was awestruck. Although I would have even better dives later on, the 15 to 20-foot visibility blew me away. Being able to see so much life would keep me coming back to Rhode Island.

Years later, I have been lucky enough to travel on assignment to remote corners of our planet: Guadalupe Island filming white sharks, sub-Arctic regions filming polar bears, and even deep in the cloud forests of Costa Rica filming warblers. But my mind always returned to Rhode Island. What if my next project was about the Ocean State? So here we are now, preparing for the launch of the Ocean State series, a look into Rhode Island and its surrounding wild coast. This first episode is particularly meaningful to me, as it revisits some of my first dives in Rhode Island.

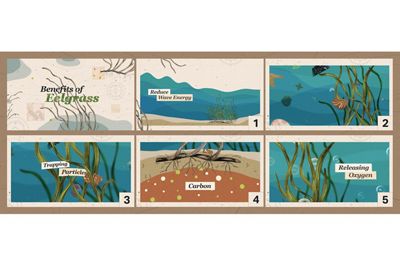

One of New England's Most Important Plants

Eelgrass (Zostera marina) is one of the world’s, and certainly New England’s, most important plants. Unlike many so-called seaweeds, eelgrass is a true plant, producing flowers, seeds and long, slender blades like the grasses in our lawns. Eelgrass is a bit of a superhero plant, boasting a range of amazing benefits. Not only does it act as a carbon sink and absorb CO₂, but it also traps ocean particles to create clearer water, buffers large waves and protects coastlines, and serves as an essential habitat for many species of fish and invertebrates. It doesn’t take long for divers to appreciate eelgrass’s benefits and beauty; its long, swaying leaves hide wonders unbeknownst to many, hence the name for this episode: Secrets of the Seagrass.

In terms of habitat, eelgrass is essential for many North Atlantic animals and their young. The catadromous American eel uses eelgrass to shelter itself from hungry striped bass on its way to the ocean to spawn, their long bodies moving smoothly through the thickets. Massive schools of silversides also hide from stripers, lying low to escape predation. A symbol of New England waters, the American lobster utilizes eelgrass both to hide from predators and to find prey. The list goes on, and it can be difficult to keep up with eelgrass’s extraordinary ability to shelter wildlife.

Eelgrass Declines

The murky water I had grown accustomed to in Long Island Sound was not always dirty and turbid; historical records show that eelgrass once lined many bays off the Sound. But the Atlantic coast has lost about 50 percent of its eelgrass, mostly due to eutrophication caused by untreated wastewater and fertilizer run-off. The excess nutrients in the water trigger massive algae blooms, which cloud the water. Because seagrass cannot photosynthesize in murky conditions, it dies, making the water even murkier.

How ironic that I grew up thinking this environment was normal, right near my hometown and that once upon a time a different environment once existed there. Chris Littlefield, TNC's conservation innovation manager, points out that the die-offs occur beyond the view of most Rhode Islanders. “Eelgrass is similar to coral die-off in that, in both cases, you can't see it,” Littlefield notes. “If it were a forest, it would be readily detectable to anyone who walks through it, but unless you go in the water, eelgrass die-off can be hard to observe."

Block Island's Great Salt Pond

Diving off the coast of Block Island feels like stepping back in time. The eelgrass is tall and lush, and the clean water can offer astonishing clarity. I personally have snorkeled there with visibility exceeding 40 feet (we even made a rough measurement).

Unfortunately, Heather Kinney, TNC's coastal restoration program manager, reports that eelgrass is losing ground in the Great Salt Pond, the island's beautiful estuary. The pond used to teem with eelgrass, but TNC's annual surveys are finding a decline in eelgrass-dependent aquatic animals, including bay scallops, which correlates with the decline of eelgrass meadows. Chris Littlefield recalls days in the late 1990s when seagrass grew so tall it reached the water’s surface. Those days are long gone, and in many areas, snorkeling in the salt ponds on Block Island and on the mainland now reveals an ocean floor more akin to my early experiences in Long Island Sound.

The Science of Eelgrass Restoration

The good news is that we have the power to change the trajectory of eelgrass die-off. During the filming of Ocean State, I sat down with one of the leaders in eelgrass research, Dr. Matt Long at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Dr. Long's lab raises eelgrass from seeds, using these “homegrown” meadows to aid in restoration efforts. It also examines water quality among dozens of other factors, building water sensors to better protect eelgrass. Their research has led to breakthroughs in understanding how to bring back eelgrass, offering a beacon of hope. Scientists at Woods Hole also provide ways for coastal communities to reduce eelgrass die-off, such as avoiding fertilizers in lawns and adjusting waste management techniques—both of which help reduce harmful algae blooms that kill eelgrass.

Meanwhile, in Rhode Island, the Narragansett Bay Commission has made huge investments in improving water quality in upper bay, which also supports eelgrass recovery. Featured in the film is Chris Dodge, the Save The Bay baykeeper, who advocates for further restoration of water quality and fish habitat, including eelgrass meadows.

Secrets of the Seagrass on PBS

This episode was incredibly enjoyable to produce. It allowed me to connect with people, institutions and communities surrounding something many people don’t even know exists. I hope that viewers enjoy seeing some of the wonders in our own backyard here in New England and Rhode Island. Through awareness, we can foster advocacy, and through advocacy, we can drive action. Perhaps one day, through collective effort, the “secrets” of the seagrass won’t be a secret anymore.

Secrets of the Seagrass, episode one in the Ocean State series, is available for streaming on PBS.org and via the free PBS Passport app. To view more of my work, you can follow me on instagram @tomaskoeck or learn more about our productions at silentflightstudios.org.