The Right to Roam: Sustaining Wyoming’s Migratory Herds

Partners think big to protect vital pathways for mule deer, pronghorn, sage grouse and other iconic Wyoming species.

Support Our Work

Your support will help TNC's work to protect at-risk migration corridors in Wyoming.

Give TodayThe mule deer are spooked. Necks stretched high and tight, ears swiveled forward, they freeze in the sagebrush. On the nearby road, a dusty Ford rattles past, the driver oblivious to four sets of dark eyes tracking him.

As the truck’s engine fades, the little group, three does and a four-point buck, warily begin to move again. They’re pacing along a barbed-wire fence that lines the road. Nosing the posts, the deer seek an opening. There is none for miles.

“My anxiety goes up just thinking about this,” says Jennifer Lamb, TNC’s Southwest Wyoming program director. “People don’t realize how many hazards these animals now face simply trying to migrate and survive.”

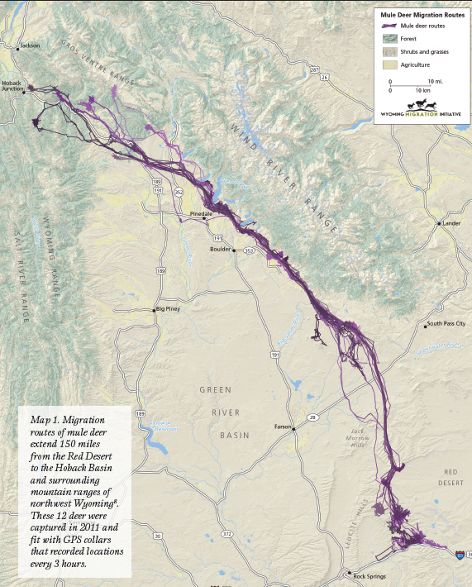

Scientists tell us these four deer, navigating the western flank of Wyoming’s Wind River Range on an early spring morning, are following an ancient path, passed down for hundreds of years from mother to fawn. A recent University of Wyoming study documented their exact route—the longest in the lower 48—a daunting 150-mile journey between their winter and summer ranges.

“What’s amazing is that the corridor is still largely passable,” says Lamb. “But that’s changing, and we need to act now to keep it that way.”

Quote: Jennifer Lamb

What’s amazing is that the corridor is still largely passable, but that’s changing, and we need to act now to keep it that way.

At the fence line, the buck tenses suddenly, then leaps. Hooves clearing the top wire, he bounds into the field beyond. The does watch him in alarm for a few seconds. Their ears rotate independently like satellite dishes, picking up the distant sound of another car approaching. Startled again, they bolt, each vaulting the fence, legs stiff. They spring off of all four hooves, flying across the pasture. One obstacle down.

But these deer, and all of Wyoming’s migrating animals, face many more barriers ahead. They have to thread their way past other roads, ponds, housing developments, yards, dogs and miles of impenetrable fencing. It’s a dangerous and draining trek that takes a toll on individuals and the species.

Since 2014, The Nature Conservancy and a group of partners have been thinking big about migratory corridors in Wyoming. What started with one-on-one rancher meetings and a few small grants has evolved into a landscape-scale effort driven by a suite of public and private partners, innovative science, millions of dollars in support and hours of painstaking labor. The results are substantial: hundreds of miles of wildlife-friendly fencing, new efforts to keep key habitat intact, improved management on public lands and a growing urgency to ensure safe passage for some of the West’s most iconic wildlife.

Roaming Is a Way of Life

The freedom to move is a big deal in Wyoming—for both people and wildlife. Often referred to as “a small town with long streets," Wyoming is one of America’s least densely populated states, second only to Alaska. Residents and visitors relish the open space. For Wyoming’s famous herd animals, that space means life itself.

Each spring and fall, mule deer, elk, moose, bighorn sheep and pronghorn are all on the move. Timing their seasonal journeys to take advantage of the most nourishing vegetation, these herds must migrate across vast expanses of public and private lands to maintain viable and productive populations.

As climate change, recreation and development increase, the landscape is changing, and the journeys for Wyoming’s ungulates are becoming more hazardous. “Migration is a stressful effort,” explains Lamb, “and we know that additional stress puts these animals at risk.” Today the herds often have to move too quickly through stopover areas—those places where they pause to rest and refuel—and crucial ranges that would otherwise provide critical food and a safe haven.

The impacts are showing. Since 1990, mule deer populations in Wyoming have declined 36% due to various factors including impacts to their habitat, predation and disease. And fences—delineating the patchwork of land ownership statewide—can be a major threat.

Deadly Boundaries

“It’s a horrible way to die,” says Lamb, describing how deer frequently get their back legs caught and tangled in barbed wire or woven fences. “They face a slow and dismal fate.”

Researchers at Utah State University determined an average of one hoofed animal for every 2.5 miles of fence dies each year from getting tangled in fence. Fawns and young deer are eight times more likely to become entangled in a fence that’s too high or has wires that are too close, but the reality is that even those animals who don’t get caught may not be able to continue their migration. They can struggle to find adequate forage, connect with mates and remain healthy. Herds can become fragmented and isolated.

Jill Randall, statewide migration coordinator for Wyoming Game and Fish Department (WGFD), puts it this way: “We’re talking about a cumulative effect. Wildlife face so many challenges in today's ever-changing world including invasive species, habitat fragmentation, disease, competition between species and many others. When they have to expend additional resources to navigate fences, we are adding one more straw to the camel's back. The difference with fences is that we have the tools and knowledge to help.”

Mapping the Journeys

In 2014 and 2015, TNC began to prioritize migration corridors, connecting with the many organizations already engaged on this issue. More and more studies were coming to light—generating valuable maps through collaring data—which energized groups like TNC who were ready to put that information to use on the ground.

The Red Desert to Hoback mule deer assessment, conducted by the Wyoming Migration Initiative (WMI) at the University of Wyoming, was one groundbreaking effort that revealed not just how far these animals travel, but also exactly where they run into trouble along their routes in western Wyoming.

The study combined fieldwork, including an aerial survey along the entire migration route, with GPS movement data from collared deer to identify the specific location of risks such as fences, road crossings, bottlenecks and development. A bottleneck is an area where the passable route narrows severely—sometimes down to a few hundred yards—and animals are forced to bunch together to pass through.

The data on the Red Desert to Hoback migration corridor, combined with valuable field knowledge from the WGFD’s local biologists, established a cache of migration information that empowered TNC and its partners. “Technology enabled us to see where the stress points were,” Lamb emphasizes. “Then we needed to do something about it.”

Momentum and Partnership in Sublette County

TNC wasn’t starting from scratch. “There were fence-improvement and habitat projects underway,” Lamb notes. “We needed to figure out how to bolster and help expand the amazing work that was already unfolding.” Armed with studies from WGFD and WMI, TNC first joined forces with partners in Sublette County, where pronghorn and deer were running up against increasing development throughout the sagebrush-covered expanse of the Upper Green River Basin.

Sublette County supports some of Wyoming’s largest and most dispersed ungulate populations. Mapping projects revealed critical bottlenecks and challenges in the mule deer migration corridor that runs from the Hoback Basin to the Red Desert. More than 4,000 mule deer use this migration route, as well as pronghorn who have been migrating between the Upper Green River Basin and Grand Teton National Park for 6,000 years.

Even with the data in hand, the work was daunting. The migration corridors traverse a complex web of private, state and federal lands managed by dozens of landowners and multiple agencies driven by different missions. Collaboration was key. “In this part of the country,” Randall notes, “relationships are everything.”

Each partner on the team brought something different to the table. TNC bolstered science studies, helped coordinate projects and brought in both private and public funding. The Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), the Sublette County Conservation District (SCCD) and the Wyoming Game and Fish Department built relationships with landowners and identified projects on the ground that would enable improved wildlife passage and connectivity. They also manage project logistics and support ranchers and landowners during the fence improvement work. Other crucial partners, including Sublette County Weed and Pest District, Wyoming Wildlife Federation and the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, contributed key resources, from wildlife expertise to invasive species removal to funding support. The Conservation Fund, the Jackson Hole Land Trust, the Wyoming Stockgrowers’ Agricultural Land Trust as well as TNC and others focus on easements and land protection in the crucial areas.

“We all have a common goal and have worked well together to use our different landowner relationships and funding opportunities to fit individual projects,” says Melanie Purcell, a wildlife & habitat program manager with SCCD. “I was surprised at how quickly the network of partnerships and relationships grew.”

Mending Fences

Making a fence more friendly to wildlife takes effort but is very doable. Top wires might be removed, or bottom wires raised up. Gates can also be installed which can be opened periodically during prime migration periods. The good news is that ranchers don’t have to give up security to be good nature stewards. If the top wire is no higher than 42 inches and the bottom strand is at least 16 inches above the ground, most wildlife will be able to get under or over fences safely, and cattle will still be contained. Ideally, the bottom strand should be smooth, rather than barbed wire, to prevent it from scraping hide from an animal and leaving it vulnerable to frostbite and infection.

In Sublette County, landowners proved vital partners. Jennifer Hayward, NRCS’ district conservationist, works with ranchers and land managers in the county willing to improve their fences. “The importance of wildlife corridors is not a hard sell,” she says. “Wildlife is a community component to Wyomingites, and the vast majority want to see wildlife and protect their viability into the future.” It also helps that landowners don’t have to tackle things alone. Partners like NRCS and SCCD help secure technical assistance and labor to make the fencing changes. Government agencies also played a role—with fencing-improvement projects unfolding near highways and on public lands.

The teamwork and energy in Sublette County have paid off. Since 2016, close to 100 miles of fence have been removed or repaired, with an additional 100 miles or more slated for repair by the end of 2021. More than $11 million has been raised by partners for fencing projects and also easements to protect critical portions of the migration corridor. Partners will work with landowners to place easements on critical properties in the migration corridors.

“By any measure, this is a remarkable impact,” explains Lamb. “As partners, we empower each other, are strategic and deliver tangible, lasting changes that are benefiting wildlife on the ground.”

Home on the Range

Today the partnerships and the progress continue in Sublette County and beyond. TNC and its many partners are using data to identify obstacles along other migration routes, pursuing more easements, controlling invasive weeds that degrade habitat quality and modifying more fences.

Partners are also hungry for more data. TNC recently joined forces with the Wyoming Migration Initiative, WGFD and the University of Oregon InfoGraphics Lab to collar animals over the entire eastern part of the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem. “We’re building science now in other parts of the state where we lack data. It would be amazing to have a true statewide picture of the herds’ pathways,” explains Lamb.

Most importantly, perhaps, TNC and its partners are continuing to expand relationships, reaching more agricultural producers, energy companies, public land managers, and public and private funders. Every mile of fence, every easement free up critical space for animals to move...and to thrive. It’s not just the deer and pronghorn who benefit. The fence improvement projects enhance overall rangeland health by allowing all kinds of animals to more readily find forage during winter months and reducing browsing pressure on native forbs and shrubs.

For people, the benefits are tangible too. Hunters, anglers and wildlife watchers spend an estimated $788 million in Wyoming each year. Preserving migratory corridors directly bolsters the state’s economic health.

Ultimately, the importance of this work goes beyond dollars, though, and it goes beyond state borders. Wyoming’s iconic migratory herds are a national treasure. The deer, elk and pronghorn have walked these same lands long before us, and, deep down, people know it’s right for them to endure.

For Jennifer Lamb, thinking back to those four deer, squeezing their way along the road in the Wind River range, this work is ultimately about hope. “It’s inspiring to see their persistence,” she says. “They will plug away, mile by mile, doing what they’ve been taught to do. They just need our help to continue doing it.”

Special Thanks

TNC is grateful for the steady and generous fencing initiative support from numerous public and private funding sources, including:

Bowhunters of Wyoming • Bureau of Land Management • Fish and Wildlife Service—Partners for Fish and Wildlife • Greater Yellowstone Coalition • Jackson Hole Wildlife Foundation • Jonah Interagency Office • Knobloch Family Foundation • Mule Deer Foundation • Muley Fanatics Foundation • National Fish and Wildlife Foundation • Natural Resources Conservation Service • Pinedale Anticline Project Office • Private Landowners • Sublette County Conservation District • Wyoming Game and Fish Department • Wyoming Governor’s Big Game License Coalition • Wyoming Landscape Conservation Initiative • Wyoming Wildlife and Natural Resource Trust • Wyoming Wildlife Federation