Karner Blue Butterfly

Get to know this beautiful, endangered, and short-lived butterfly and what we're doing to protect them.

Karner blue butterfly facts

Scientific name: Plebejus melissa samuelis

Federal status: Endangered

Habitat: Mix of open and closed canopy habitats, oak savannas, barren sandy areas

Diet: Variety of native flowers (beebalm, cinquefoil, blackbery, leadplant, milkweed); larvae only eat wild lupine

Meet the Karner Blue Butterfly

A subspecies of the Melissa blue butterfly, the Karner blue (Lycaeides melissa samuelis) is a relatively small butterfly, averaging around one inch in wingspan. Males’ wings across the top are silvery blue to dark blue with narrow black margins. Females are graying brown with bands of orange inside the blade border.

Karner blues are found around the Great Lakes and the northeast United States, typically in semi-shaded areas with sandy soil. They are fairly sedentary for a butterfly, rarely venturing farther than 300-600 feet from their hatching place.

Karner blue life cycle

There are two broods each year of the Karner blue butterfly. The first set of eggs hatch in April. Larvae feed for a few weeks before cocooning. Adults emerge from cocoons and fly during the first 10-15 days of June.

Those adults lay new eggs, which hatch about a week later. These larvae also feed for a few weeks, and cocoon and fly as adults in mid-August. Their eggs don't hatch until the following spring.

Adult karner blue butterflies have a very short lifespan, usually only five days or so. Some females have been recorded living up to two weeks. Larvae feed only on the wild lupine plant. They have a symbiotic relationship with ants. Ants protect the larvae from predators and in return feed on a liquid it secretes.

You Can Help Karner Blue Butterflies

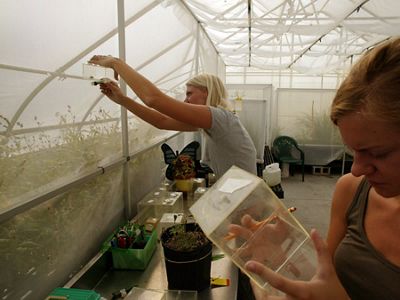

The federally endangered Karner blue butterfly relies on Lupinus perennis as a larval host plant. You can start wild lupine from seeds or purchase seedlings from nurseries specializing in native plants.