The Secret Life of Eels

A pair of studies offer a tantalizing glimpse at the mysterious life cycle of the American eel.

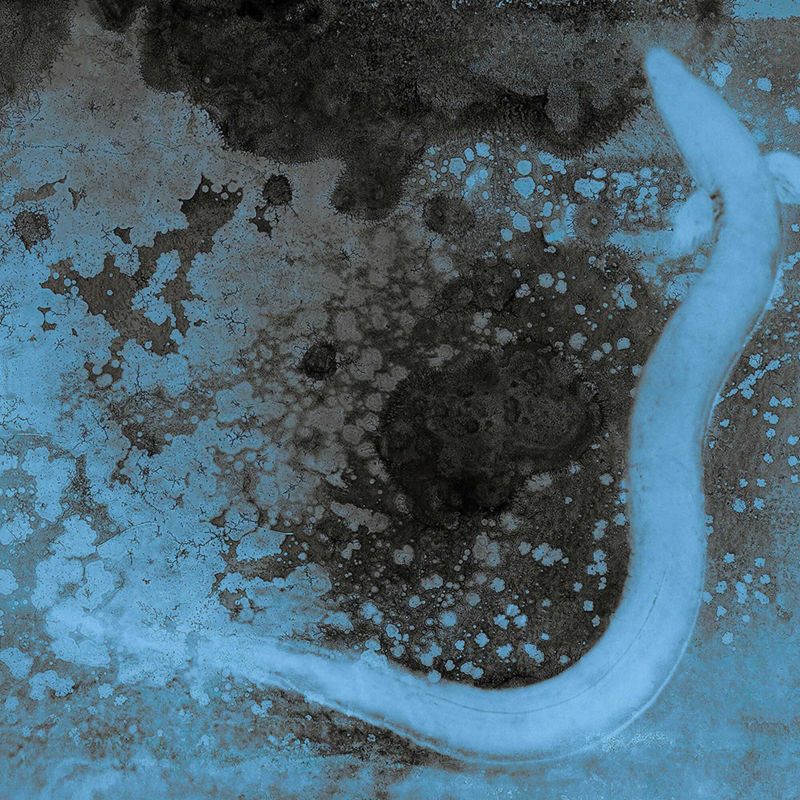

Text by Jenny Rogers | Photo Illustrations by Christine Fitzgerald | Issue 1, 2024

The eels wait for the new moon. Then, hidden in the darkness, they move, rippling down the Delaware River in an ancient annual mass migration.

For many years, the eels matured in the healthy freshwater habitat of the Upper Delaware, but natural instincts—and other unknown factors—have impelled them to uproot their lives. Now they begin a final months-long migration to the place of their birth: the Sargasso Sea, at the intersection of four Atlantic currents. There they’ll spawn, laying tens of millions of eggs in the open ocean, and die.

At least, that’s what the scientists think happens.

“Eels can live in our rivers for about 15 years. And then on some [usually stormy] night in the middle of fall, some take off and go back to wherever they came from,” says Mari-Beth DeLucia. She’s the director of land protection for Pennsylvania and Delaware for The Nature Conservancy, and she’s on the anguillid eel specialist group for the International Union of Conservation of Nature (IUCN), which is a global United Nations-associated conservation group. “But that’s not very scientific.”

Many mysteries enshroud the American eel. First, no one—not a scientist nor the crew of a fishing boat—has ever witnessed eels spawning in the wild, which would be a crucial step to learning exactly where eels reproduce and thus what habitat they need. Only in the last 12 years have scientists put tracking devices on American eels and mapped their journey to their spawning grounds in the Sargasso Sea. And what triggers the eels to start that final migration? There are a lot of theories, but nobody knows for sure.

Meanwhile American eels are considered endangered by the IUCN, which publishes a global list of threatened species. After decades of declines, the American eel population has stabilized at a historic low. They were hit hard by overfishing; there’s a lucrative global industry for young eels that has at times made poaching off the U.S. Atlantic coast more common. Another lingering, longstanding threat has been the loss of the freshwater habitat they, and so many other fish, rely on for much of their lives. Freshwater ecosystems are some of the most threatened in the world—broken up by dams and polluted by agriculture and cities. In the case of eels, large dams on rivers throughout the U.S. East Coast block migrations both upstream and down, and hydropower turbines sometimes chop up the adults as they make their way to the sea.

A pair of simultaneous research projects are trying to shed some light on the eels’ migration. The scientists have begun tracking adult eels as they migrate down the Susquehanna and Delaware Rivers to identify what environmental triggers launched these movements. Because the Delaware has no major dams and the Susquehanna has four, the twin research projects offer a tantalizing opportunity to pinpoint what conditions spark the eels to migrate and how obstacles like dams affect their migration to the Atlantic Ocean. If the two teams can identify what makes the eels begin their trek, they might be able to predict their migrations in the future. The answers they find will go a long way toward protecting migrating eels.

A Curious Fish

The phone rings. When Jessica Best, a New York state biologist, answers it, a fisherman on the other end of the line tells her what she’s been waiting to hear: The eels have arrived.

She calls the other researchers. DeLucia gets in her car and drives four hours north to a meeting point along the Neversink River, a tributary to the Delaware. Others come, too. There’s Dewayne Fox, a biologist and professor for Delaware State University, who is the principal researcher for this project. Best and Amanda Simmons are both New York biologists for their state’s Department of Environmental Conservation. And there are the weir fishers. Fishing weirs—rock or wood enclosures built in the river to capture fish as they move up- or downstream—have been used since ancient times by Indigenous Peoples and other fishers.

Fishers hand over several eels to the biologists, who work quickly to surgically insert tiny transmitters. After sewing up the eels, the scientists watch the fish slither away downstream. As they pass underwater receivers placed throughout the river’s length, the tiny transmitters inside them will ping.

About 20 years ago, when DeLucia was just starting her career, she noticed that very few people in the research world seemed to be talking about eels. “Eel numbers were crashing, and nobody knew why,” she says. “But nobody had any information because nobody ever cared about eels.”

It’s a complication that other researchers cite, too. Eels have captured the imagination and horror of the general public for centuries, but they’re not studied as much as, say, American shad or Atlantic sturgeon.

Quote: Mari-Beth DeLucia

Eel numbers were crashing, and nobody knew why, but nobody had any information because nobody ever cared about eels.

“They’re probably unattractive to many people. A lot of folks think they look like snakes—or they think they are snakes. You know, they’re not a warm and fuzzy fish,” says Sheila Eyler, a project leader for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Mid-Atlantic Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office. Eyler has studied eels and, as she puts it, other “ancient things” for decades. “They’re very cryptic.”

They’re not snakes, or even reptiles, of course. American eels are ray-finned catadromous fish, which means they live much of their lives in freshwater rivers and estuaries but spawn in the ocean. That makes their life cycles the inverse of those of other migratory fish that, like salmon, are anadromous—meaning they live in the ocean and spawn in rivers.

Each year American eel eggs hatch into leaf-shaped larvae in the Sargasso Sea and float along the Gulf Stream and other ocean currents until they reach the eastern seaboard of the Americas. By this point they’ve grown into transparent, androgynous “glass eels.” As they migrate upstream, they’ll grow into 4-inch “elvers” and then larger “yellow eels.” Over time, females may travel farther upstream than males due to their larger size. After more than a decade in freshwater habitat, they’ll undergo a process called “silvering,” where adults will sexually mature, growing larger eyes and larger stores of fat as they prepare to begin their migration back out to sea.

That life cycle has intrigued some people for millennia. Ancient Egyptians believed eels were associated with the sun god Atum, created when the sun warmed the Nile. Aristotle, puzzled by the eel’s ability to appear in land-locked pools after rain, hypothesized that they emerged spontaneously from the mud. A young Sigmund Freud reportedly dissected young eels, searching for sex organs that were not there.

Fascination has borne out even as researchers have begun to answer some questions. Danish biologist Ernst Johannes Schmidt discovered in 1921 that European eels—a cousin of American eels—migrate to the Sargasso Sea to spawn. He reached this conclusion after years spent systematically trawling the ocean in search of ever-smaller eels. A century later, scientists confirmed that journey using satellite tags on adult European eels. Still, no one has witnessed eels breeding in the wild—something DeLucia calls the “Holy Grail” of eel scholarship in part because, in a changing climate, understanding their habitat needs could become critical to maintaining the species.

“If things are changing and they rely on the Gulf Stream to ferry larvae back to the coast and that starts to shift, not knowing where they start is a problem,” she says.

Scientists aren’t the only ones on the hunt for eels. Prized as a staple in foreign cuisines, eels cannot spawn in large-scale aquaculture settings. That has led aquaculture businesses to seek out glass eels to raise. The U.S. glass eel harvest is banned in all but South Carolina and Maine, where it’s regulated and lucrative. (A single pound of glass eels, harvested legally in Maine, can sell for more than $2,000.) Globally, the trade is so profitable that young eels are said to be more valuable than their weight in heroin. In 2018, the head of the Sustainable Eel Group, Andrew Kerr, called the multibillion-dollar eel black market the “biggest wildlife crime by value on Earth.”

Listening for Evidence

As DeLucia, Fox and their colleagues were just beginning their eel-tracking research on the Delaware River, a nearly identical effort was underway just 60 miles west on the slow, rolling Susquehanna River.

The Susquehanna is everything the Delaware is not. The Delaware River, flowing 330 miles from Hancock, New York, to the Delaware Bay, is the longest free-flowing river in the eastern U.S. It provides drinking water for millions of people in the Northeast and is the site of a landmark environmental effort that stopped the construction of a major dam in the 1970s.

The 444-mile Susquehanna River, meanwhile, has four major industrial dams on its first 76 miles. The oldest of them, the York Haven Dam, began operations in 1901, effectively closing off the river to natural fish migration for decades. Even after effective fish passages were installed in the 1990s, eels didn’t return upstream in any real numbers until the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began trapping them south of the lowest river dam and moving them to spots north of the highest dam. Without this intervention the waters upstream of a dam lose eels, which are a top predator, creating imbalance in the structure of that aquatic community.

Many questions remain about eel behavior in the Susquehanna, Eyler says. The agency doesn’t know when they migrate or for how long, and it also doesn’t know how the eels interact with the hydropower plants as they come downstream. To answer some of those questions, owners of the four Susquehanna dams contributed money to fund a broad study on the animals. The research project would, coincidentally, be remarkably similar to the one DeLucia and Fox had designed nearby.

In 2021, the service launched a trial acoustic telemetry project, followed by a full-scale version in 2022 and 2023. Each of the latter years they caught about 100 female silver eels in the upper Susquehanna and surgically inserted tiny acoustic tags into them. Then they waited for the eels to pass receiver arrays placed throughout the waterway. The devices—something akin to hydrophones—can “hear” when a tagged fish swims by.

At the same time, Eyler and her team noted water temperature, water flows and lunar phases. “We’ll see if those have any relation to the fact that the eels start moving at a particular time,” Eyler says. Any information the team learns can guide the dam operators, which are required to have an 85% eel survival rate. If not enough eels are surviving their migration through the dams, Eyler says, the operators will have to take new steps to protect eels. Knowing when the eels arrive each year would at least tell the dam operators when to act. But knowing what to do will require additional research. One possibility might simply be to turn off turbines for a short time to allow eels to migrate through unharmed.

Magazine Stories in Your Inbox

Sign up for the Nature News email and receive conservation stories each month.

A Tale of Two Rivers

In September 2023, after two seasons of data collection, DeLucia is excited. She and Fox first dreamt up this project 13 years ago, but it took a decade to find the funding to make it happen. Both TNC and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation contributed and are supporting the effort. Now, the data are already revealing new and surprising facts about eels. For one thing, the migrating eels in the Delaware move fast. But more curiously, the eels in 2022 also moved in two spurts, seemingly gathering in spots in mid-October and again in mid-November.

“It looks like they are swept down the river and then they kind of wait,” DeLucia says. Then in another pulse, they move down to the tidal portion of the river. It raises new questions, she says. The fish, while migrating, do not eat. “So, what are they doing?”

In the coming months the teams on both rivers will download data from the receivers along the waterways. They’ll compare the new information with the previous year’s data, and, eventually, they’ll analyze what the differences in their datasets mean about the two rivers.

Throughout 2024, the teams will analyze their collected data. For the Susquehanna, knowing how eels act on an undammed river will be valuable in understanding the impacts of hydropower on the fish, Eyler says. Meanwhile, DeLucia is just hoping fewer eels get caught in turbines.

“My hope is that what comes out of this can actually make some difference on these dammed rivers, that it’ll give the opportunity for managers to keep managing for power but also be able to protect these eels for one or two nights of the year that they shut it down,” DeLucia says.

In the meantime, new studies beget ever more new studies. Eyler will eventually move on to researching exactly what percentage of eels actually survive a trip through dam turbines—and what dam operators can do to improve the numbers. And DeLucia is dreaming up studies to answer new questions about eels: their population dynamics, how they breed and ultimately how large a population is needed to make the American eel sustainable.

“That’s the million-dollar question,” she says.

About the Creators

Jenny Rogers is a senior editor and writer for Nature Conservancy magazine, where she most recently wrote about efforts to protect Georgia’s sea turtles.

Christine Fitzgerald, a photo-based artist out of Ottawa, was a finalist for Royal Photographic Society’s International Women Science Photographer of the Year 2023.