Wild Empire

Mongolia closes in on its goal to protect nearly one-third of the country and the rare species that call it home.

Fall 2020

From the grassy seas of the eastern Steppe to the lofty peaks of the Altai Mountains, with forbidding expanses of Gobi Desert and wide belts of boreal forest in between, Mongolia is a land of mind-boggling scale and tremendous ecological importance.

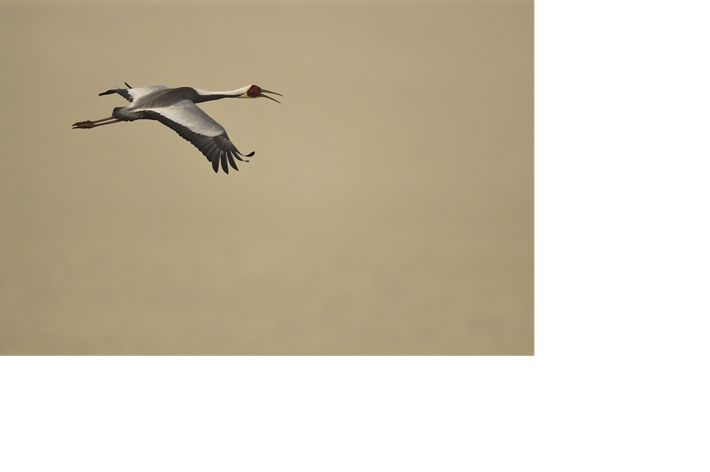

The country is perhaps best-known for its vast grasslands, which sustain more than a million gazelles. But it is also home to a menagerie of species that challenge the imagination: the elusive snow leopard, a Pleistocene-era Muppet-nosed antelope and a trout so big that it preys on beavers.

Last year, as part of a long-term quest to safeguard Mongolia’s rich natural heritage, the nation’s parliament expanded its system of protected areas by 8.6 million acres—an area larger than Yellowstone, Yosemite, Grand Canyon, Glacier, Canyonlands, Olympic, Everglades and Great Smoky Mountains National Parks combined. Then, in May of this year, lawmakers added another 3.2 million acres of nationally protected habitat for some of the country’s most endangered species.

Quote

In conservation, you're always competing against time. Developers can move very fast.

Combined, these efforts bring the total amount of land under national-level protection to some 80 million acres and push Mongolia more than two-thirds of the way toward its decades-old goal of putting 30% of the country’s land under national-level protection by 2030.

“Can we afford to do this?”

But the path to this point hasn’t been easy. While much of the country is largely untouched, some areas are intensely exploited. After Mongolians threw off generations of Communist rule in 1990, the nation looked toward its tremendous resources of copper, gold, coal and other minerals to drive development. By the mid-2000s, more than 40% of the country’s territory had been leased for mining and mineral exploration. Many Mongolians took to the streets in protest, and citizens began grappling with hard questions about the future of the environment—and the country itself.

Galbadrakh Davaa, director of The Nature Conservancy’s Mongolia Program, says balancing development with the protection of key natural areas was a question of competing priorities. “Everybody was worried,” he says. “Can we afford to do that as a developing country?”

In 2008, TNC partnered with the Mongolian government, Mongolian Academy of Sciences, WWF Mongolia and UNDP Mongolia to help the country find an answer before it was too late.

“In conservation, you’re always competing against time,” Davaa says. “Developers can move very fast. We can’t always get ahead of the curve.”

In 2009, TNC carried out a rapid, year-long ecological assessment of Mongolia’s Eastern Steppe, followed by similar surveys for the Gobi in the south, the Altai Mountains in the west, and the Khuvsgul Lake and Khangai Mountains region in the north. Those assessments helped the government identify critical areas that would collectively protect biodiversity and serve as a blueprint for expanding the country’s network of national and local protected areas.

“Globally, most national protected-area systems only represent a subset of habitat types. High mountain ‘rocks and ice’ are easy to protect because there are few competing economic values,” says TNC conservation scientist Mike Heiner, who helped carry out the ecological assessments in Mongolia.

“Mongolia’s protected-area network represents a full range of habitat types, and that is unique.”

Today, TNC continues to provide scientific support to community-based organizations advocating for protection of ecologically and culturally important areas. That has helped drive a broad effort by local governments to protect an additional 66.4 million acres of land—some of which could be incorporated into the national government’s final-stretch push to conserve 30% of Mongolia’s land by 2030.

Scroll down to see images from the incredibly varied regions of Mongolia.

NORTH

Lake Hövsgöl and the Khangai Mountains

EAST

The Steppe

SOUTH

The Gobi Desert

WEST

The Altai Mountains