Heart of Appalachia

TNC has a plan for safeguarding biodiversity in the face of climate change—and it starts with protecting 253,000 acres of central Appalachian forests.

Winter 2019

When visitors hike up to the Pinnacle Overlook observation deck at Cumberland Gap National Historical Park to view the valleys below, they are standing almost at the spot where the borders of Virginia, Tennessee and Kentucky meet. What may not be obvious from the lookout is that the rugged landscape of rolling Appalachian woodlands was once a bustling crossroads of industry and culture that helped shape much of the eastern United States.

The namesake Cumberland Gap—a low break in the central Appalachian Mountains—used to be a well-trodden route for Native Americans and then early settlers of European descent moving east and west through the area. (Daniel Boone led a team through the gap to settle in Kentucky.) When the railroad arrived in the late 1800s, the forests here supplied the lumber that built many eastern towns and homes, and the mountains were mined for coal that fired the Industrial Revolution.

Today, those extractive industries run at a fraction of their former strengths. The landscape bears their pockmarks in the form of closed mine sites, old logging roads and an economy that has withered with those industries.

Despite the long shadow of history here, when Will Bowling, The Nature Conservancy’s Central Appalachians Project director for Kentucky, looks down from the Pinnacle Overlook, he views things quite differently: He sees the future. That’s because Bowling is helping to drive one of TNC’s most ambitious efforts to date—a project that will not only protect some of the most critical wildlife corridors in the eastern states, but also could help diversify the battered economy in the heart of coal country.

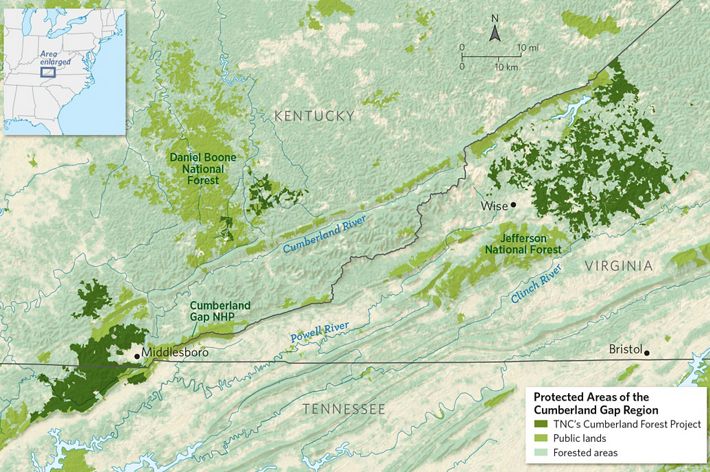

The framework for this vision took shape earlier this year when TNC created an investment fund to purchase properties totaling 253,000 acres, some with history in the coal and timber industries. The large parcels reach into all three states in the Cumberland Gap area: Kentucky, Virginia and Tennessee. It is one of TNC’s largest-ever land deals in the United States.

“It’s pretty hard to get your mind wrapped around the scope of the property,” Bowling says. “But it’s a large enough scale that we’re really going to be able to move the needle so that we can be sure we have a highly functional landscape here in a hundred years and beyond.”

Despite more than 150 years of logging and mining, the central Appalachians have some of the highest recorded levels of biodiversity in the eastern United States. The purchase will help protect rare populations of salamanders, freshwater mussels, elk and other at-risk species. Perhaps more important, the region has been identified as a critical south-to-north corridor that scientists expect will enable the movement of species as the climate continues to warm.

The first of the two acquisitions was the Ataya property, 100,000 acres straddling the Kentucky-Tennessee border acquired in April. It’s largely composed of current and former working forests and coal mines. The second purchase was the 153,000-acre Highlands-Lonesome Pine property in southwestern Virginia, which was acquired in July. It’s just as sprawling but looks like Swiss cheese on a map because one of its prior owners—a coal company—assembled the property by buying many individual parcels over a long period of time.

Buying such a large property takes serious money, and in this case much of the funding came from a relatively new source: impact investing, which leverages private investment capital to support conservation projects that have the potential to earn a profit.

The plan is to treat the Cumberland properties a little like a fixer-upper house. Over the next decade, TNC will begin restoring the forests. Where appropriate, it will implement Forest Stewardship Council-certified sustainable logging operations to generate income through sustainable forestry. The properties are also enrolled in California’s carbon offset market, which allows the project to generate revenue—even if trees are not cut—by recognizing the value of the carbon stored in the forest. Meanwhile, some of the properties already came with access leases to local hunting and fishing. And there are plans to make other areas available for use by local outfitters in the growing outdoor recreation industry.

All of these activities will use local contractors and support green jobs to the local economy. “It’s about finding that nexus between providing conservation while still maintaining the human relationships with the properties,” Bowling says, adding that the plan is not to lock people out of the land, but to prove that conservation can be an economic driver.

A decade or so down the road, the project aims to sell the revitalized land to new private and public owners. The project will seek to place restrictions on as much of the property as possible to ensure that sustainable management continues. On the heels of TNC completing the Cumberland Forest Project acquisitions, Virginia Governor Ralph Northam announced in August that the commonwealth’s largest-ever open-space easement will permanently protect nearly 15% (22,856 acres) of the Virginia portion. In his statement, Governor Northam said, "This unique partnership … will allow for sustainable forestry, improve access to outdoor recreation, and increase protection of wildlife habitat and water quality." The carbon projects require sustainable forest practices for at least 100 years.

The promise of this approach is already evident in St. Paul, a town in southwest Virginia that was once a hub of the regional coal industry. Throughout the last century, its fortunes rose and fell with the price of coal—and recent market declines have taken the town with it.

In the 1990s, TNC launched its Clinch Valley Program, which aimed to restore waterways and forests around the nearby Clinch River. In the process of conserving its natural resources, the town has recently started to a see a spike in economic vitality—not from coal, but from recreation.

“The Nature Conservancy has always been involved on the fringe of everything we’ve done and sometimes smack in the middle of it,” says Lou Wallace, a community leader who serves on the local Russell County Board of Supervisors. She’s also the founding director of St. Paul Tomorrow, which seeks to craft a “diverse, creative economy” to replace dependency on coal, in part by promoting biodiversity and access to nature as a genuine community asset.

Signs of the initiative’s success are everywhere in town. Outdoor adventure companies report a surging number of people making use of the Clinch River and surrounding lands for pursuits ranging from kayaking, tubing and ATV trail riding to hiking and fishing. One outfitter has launched regular volunteer river cleanups. (“People used to toss old tires in the river,” Wallace says. “Now, they’re pulling them out.”) A new boutique hotel with a farm-to-table restaurant caters to tourists, while a recently opened microbrewery, using water from the Clinch, is doing a brisk business.

“People are starting to understand that we can live in harmony with our environment and still make money,” Wallace says. She thinks TNC will succeed with the Cumberland Forest Project to the extent that it can advance both objectives. “I do know that they are going to be good neighbors and good partners, because I have learned that over the past 20 years,” says Wallace. “If it wasn’t for their work, some of the things they’ve been doing, we wouldn’t be as far down the road as we are.”

Conservancy staffers hope to replicate this formula on an enormous scale through the Cumberland Forest Project. “The plan has elements that are local, regional and ultimately global in scale,” says Brad Kreps, who directs TNC’s Clinch Valley Program in southwest Virginia. He is chomping at the bit to see how much growth, both economic and environmental, TNC can achieve across the Cumberland Gap region. “This area is so rich, it’s got all of the ingredients. With some conservation-oriented thinking and management, I think we’re going to be amazed by what happens.”

BIODIVERSITY CROSSROAD

The Conservancy’s Cumberland Forest Project sits in the heart of the central Appalachians, one of the most biologically rich regions in the eastern United States. Unlike the northern stretch of the Appalachian Mountains, this area was not blanketed by glaciers during the last ice age, which allowed many more species to thrive here. As a result, the central Appalachians are now home to an extraordinarily high number of plant and animal species that are found here more than anywhere else. The 253,000 acres that TNC now manages here are home to curiosities like the golden-winged warbler, Northern long-eared bat, multiple species of endangered freshwater mussels, and native fish like the Kentucky and Cumberland arrow darters.

For ecologist Mark Anderson, TNC’s director of conservation science for the eastern United States, the Cumberland Forest Project represents the culmination of a career’s worth of research. The TNC team that he works on predicts that this area will be an instrumental refuge for protecting biodiversity as the climate changes. They study how species move in response to disruptions in their environment.

“The climate is changing, which means that temperature and moisture regimes are changing,” Anderson says. “In response to that, our tree populations are slowly shifting from where they are now to where they will probably be in the future.” These north-south-running mountains offer a wide range of microclimates, some of which can act as suitable habitats for plant species adapted to wetter or cooler conditions, allowing them to repopulate farther north or higher up in elevation as temperatures increase.

And when the vegetation shifts, animal species go along with it, says Anderson. “So we’re really having a transition of nature on the landscape.” That’s why connecting large swaths of protected land will be crucial to preserving biodiversity in the face of climate change. Even more important, according to Anderson’s most recent research, is protecting critical areas that link key habitat. “The models highlight the Cumberland area as one of the really important linkages,” he says. “We found that you have a relatively large number of species moving through a relatively small area.”

Studies have found that the ranges of plants and animals are already shifting in response to warming temperatures and changes in moisture. For example, the range of eastern hophornbeam trees has shifted 25 miles north and 48 miles west as the Midwest has become wetter and warmer over the last 40 years. The range of musclewood trees has shifted north at a rate of almost 6 miles per decade. And as the trees move, so do the animals.

The next step, says Anderson, will be studying the outcomes of this Cumberland Forest Project. It will take a few years to see how well the purchase protects lands for species moving in response to a changing climate, but he feels confident that what is learned here will provide a foundation for new land-protection projects everywhere.“What’s really exciting about the project is that it elevates our conservation to a new level,” he says—a level where TNC can include resilience to climate change as a factor in our decisions about what land to protect. “And we think it will become a model for other projects throughout the United States,” says Anderson.

THE PURCHASE

While the land deals were completed this year, the Cumberland Forest Project has been a long time in the making. In 2007, TNC and Tennessee state agencies collaborated to establish the 140,000-acre North Cumberland Wildlife Management Area. Elk reintroductions there and in nearby Kentucky (led by the states and their partners) have re-established some of the largest elk populations east of the Mississippi.

Having achieved that, TNC’s Central Appalachians staff started looking at a neighboring property just to the north—the 100,000-acre Ataya tract—to create an even larger corridor of protected land and expand on the state and federal lands already protected in the area. “Ataya became like the Holy Grail for us,” says Gabby Lynch, director of protection for TNC in Tennessee. “We’d always known about this huge property, but never could imagine us being able to [afford] it.” In Virginia, TNC staff had similar thoughts about 153,000 acres of logging and mining land. “We couldn’t dream up how to come up with the money,” says Brad Kreps, TNC’s director in the Clinch River Valley area—that is, until the project discovered a solution through impact investing.

Since 2014, TNC has turned to impact investing with its NatureVest team—who work with investors to put money into conservation projects with the goal of achieving conservation and a financial return—to help tackle huge deals when there is a business case for conservation. The Cumberland Forest Project, which totaled $130 million for 253,000 acres and 2 million tons of carbon offsets, is the largest land transaction TNC has ever handled using funds from impact investors.

“It’s one of those projects you can probably see from space,” says Tom Hodgman, TNC’s deputy managing director for forest investments. “It’s a game changer when you can pay for this much conservation by using investment capital.” He first set foot on the Ataya property in 2013, and along with TNC’s Central Appalachians team, he’s been working on the Cumberland Forest Project ever since.

The land is now owned by an impact investment fund and will be managed by TNC until its sale in about 10 years. The project intends to place new easements and covenants on as much of the land as possible to ensure that the next owners continue to maintain the land’s biodiversity and manage its forests in a sustainable manner.

Another key difference that separates this deal from a traditional conservation land purchase is that the funders—the impact investors—expect to make a return on their money. That means in addition to protecting biodiversity, the purchase will need to generate revenue as well. The expectation is to use sustainable timber harvesting together with other measures that will improve the health of the forests. Sustainable forestry will also help generate credits in North American carbon markets that can be sold to companies looking to offset their emissions.

Other opportunities for revenue include the sale of leases and licenses for recreation, hunting and fishing. But some of the most interesting possibilities for generating funds include repurposing former mining sites. Since the land has already been leveled at some former mining areas, says Kreps, “one of the things that intrigues us is the potential for solar [power development].” And yes, the irony of building renewable energy farms on former coal mines is lost on no one.

THE CONSERVATION VISION

The Cumberland Forest Project lands cover nearly 400 square miles—almost the size of Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado—but that only hints at the potential reach of this project’s impact. The newly purchased properties are also ringed by (and in many places connected to) state and federal forests, parks, and other preserves, establishing a truly regionwide haven for conservation.

This project represents a rare opportunity to protect one of the most diverse ecosystems in the United States. That’s a consideration that guides the daily work of Stuart Hale, TNC’s Central Appalachians forest manager. Lately, he has spent a lot of time planning how to restore the forests through active management practices, like sustainably harvesting trees. That means taking stock of which areas could benefit from forest-management treatments and which ones could be left alone to generate carbon-credit revenues.

“Historically, you had two assets: the land itself and the timber growing on it. Now, we’re able to add an additional asset class: carbon, and carbon’s starting to play a larger role,” Hale says. And even after years of mining and logging, he says, “the science is indicating that we are going to be able to get back some good forest on these sites.”

Hale says that past management and changing conditions have resulted in forests different from those historically present here. Over time, species like maples and poplars expanded their presence, stealing resources from more desirable species such as nut-bearing oaks. Future forest-management efforts will focus on harvesting less desirable trees and restoring biodiversity to the forests. “When we have a great mix of trees, the forests support more wildlife and are more resilient to disturbance and the risks of climate change,” Hale says.

Besides improving the forest, TNC aims to prove that conservation can reignite the local economy. Forest management, restoration and possible solar energy development will require help from the local workforce. And opening the lands to recreation will help attract more visitors to the Cumberland region.

All mineral royalties inherited with the land will be completely dispersed among area nonprofits that support conservation and nature-based economic development. Since TNC doesn’t own the mineral rights on the properties—and is subject to agreements made by prior owners—the organization can’t control the mining that happens at some sites. But the plan ensures that every penny it receives from mining royalties will be directly reinvested into the local communities.

The possibilities inherent in the project come with the weight of the responsibility to see it through. “It’s a huge conservation win, but we’re also doing this in the heart of one of the most economically challenged parts of the country,” Lynch says. “We want to figure out how we [can] actually manage these properties in a way that creates positive returns through this investment model and creates value for communities that are searching for a future that includes a more diverse and sustainable economy.”