Shared Traditions

A growing national group is trying to make hunting—an overwhelmingly white sport—more accessible and equitable for others one weekend at a time.

Summer 2023 Issue

One morning in early November, I sat in a hunting blind at The Nature Conservancy’s Mashomack Preserve on Shelter Island, near the eastern tip of Long Island. To my side was Avery Toledo, a contract management specialist from the Bronx, holding a compound bow. We could hear a deer snorting and see movement in the brush about 30 yards away. It was an electric moment: Trying to stay as still and quiet as possible, we held our breath and waited to see if it would show itself enough for Avery to take a shot.

Elsewhere in the preserve, seven other pairs of hunters were also waiting in blinds, scanning their surroundings and hoping luck would bring an animal within range. We were all part of a training weekend organized by Hunters of Color, the only nationwide hunting nonprofit led by people of color, for people of color. Over two days, eight recruits—most from New York City, 90 miles west—were paired with experienced mentors, including myself, who taught them the ins and outs of hunting with modern compound hunting bows.

When our deer moved on, Avery and I could feel the shiver of ebbing adrenaline. It’s moments like this that make me feel incredibly connected to the natural world—a feeling I hope to help others who look like me experience as much as possible.

I’ve been hunting and fishing almost as long as I can remember. Generations of men in my family have hunted for subsistence and as a way of life, mostly deer and small game, going back to our enslaved ancestors. Growing up in southern Louisiana, I was lucky to have my father and uncles as mentors to teach me how to be a safe and conscientious hunter and angler. Whether it was in Louisiana, Texas or Mississippi—all places we traveled to hunt—I loved the freedom of being outdoors and doing something that was both challenging and fulfilling. It was also practical, since we ate everything we harvested and wild game was commonplace at the dinner table.

Above all, my relatives passed down their deep connection to the land. That dedication and commitment to the natural world, treating it with admiration and respect, was something I always admired. In many ways, it shaped who I am and how I navigate through the world.

Moving to New York City to start an MD/PhD program at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai was a big adjustment, to say the least. I needed to find an escape from the demands of school and the confines of my tiny apartment in upper Manhattan. It took some exploring, but I slowly started to discover how many opportunities there are for outdoor recreation within driving distance of the Empire State Building—places like the Catskills, the Hudson River Valley, even right next door on Long Island.

Once again I was able to recharge my batteries outdoors, hunting deer and waterfowl and fly-fishing all across New York state, from Long Island to the Adirondacks. But wherever I went, I couldn’t help noticing how I was often the only person of color with a shotgun or fishing rod. It reminded me how lucky I was to have a deep background in the outdoors—and it made me want to pass on my knowledge and experience to other people. I felt it wasn’t just a duty but an obligation.

So, naturally I was excited to connect with the folks at Hunters of Color (HOC), whose goal revives a long history that starts with Indigenous communities who hunted and fished for subsistence thousands of years ago. Founded in 2020, the group works to increase access and opportunity for people outside the typical hunting demographic through mentored hunting events, like this one at Mashomack, and community building. Reconnecting people of color to the outdoors revives these traditions and creates passionate conservationists in the process. As the New York state ambassador for HOC, I’m proud to pass on my experience to others and help them connect with the world beyond the skyscrapers.

People are often surprised to learn that hunters and anglers provide a majority of the funding for conservation in the U.S., mostly through taxes on hunting gear, clothes and licenses. In fact, hunting alone contributes $1.5 billion a year to funding state and local wildlife agencies through the Pittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration Act and Dingell-Johnson Sport Fish Restoration Act, which support recreation and conservation causes in the U.S. A large portion of that money goes to conservation agencies, including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and local environmental departments, where it pays for things like habitat restoration and wildlife management and research projects. After all, it’s people who spend the most time in wild places who are the most invested in protecting them, and not just through their wallets. It’s hard to find a hunter or angler who isn’t also an ardent conservationist.

It’s important that people of color see themselves represented in this bigger picture. One of the inspirations for the creation of HOC was a survey by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 2016 that found 97% of hunters and 86% of anglers were white, and the majority of both were 45 or older. In creating a safer, more inclusive space in the hunting world, we’re trying to show that the sport and lifestyle are open to anyone.

Hunters By the Numbers

-

$1.5 B

The estimated amount of money hunting, fishing and boating equipment taxes contributed to recreation, education and conservation this year

-

97%

The proportion of registered hunters in the U.S. who identified as white in the most recent U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service survey

-

4.8%

The percent of the U.S. population registered as hunters

-

7.5%

The percent of the U.S. population that registered as hunters in 1968

-

$1 B

The amount of money generated by the sale of hunting licenses in the U.S. this year

Hunters of Color

Learn more about why TNC has partnered with HOC

Hear an interview with a HOC founderBut the barriers can be steep, whether it’s training, acquiring gear or simply getting land access. That’s why HOC organizes these mentorship events—where we teach hunting skills, safety and ethics to people who otherwise might not have a chance along with community events like river cleanups and habitat-restoration projects. Meanwhile, in New York, The Nature Conservancy manages 160 preserves (about 81,000 acres in all), allows deer hunting in some areas as a conservation tactic, and has been focused on providing more equitable access to nature. A partnership made sense.

One of our first mentorship events was in 2021 at the Hannacroix Ravine Preserve near Albany. The three-day program was run in collaboration with TNC, the National Deer Association, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and Backcountry Hunters & Anglers. We paired a small group of participants with mentors who taught them how to hunt, butcher and prepare white-tailed deer for the table.

Everyone enjoyed the weekend so much that we immediately started planning the next one. On a Saturday in late September 2022, we partnered with TNC and Backcountry Hunters & Anglers to bring 35 prospective hunters to the Eugene and Agnes Meyer Preserve in Armonk, about an hour north of New York City, to learn archery and train for the archery deer season. Most of the would-be hunters were from the city and had zero experience with hunting or archery. Some had heard about the program on Instagram.

The Nature Conservancy provided the bows and HOC provided the training. We set up 3-D target stations throughout the preserve to simulate real hunting scenarios. Vertical bow hunting is difficult, but even though we only had one day together, mentees left with a good grasp of the basics.

Two months later, the Mashomack weekend brought eight of those new hunters to Shelter Island, a two-and-a-half-hour drive and short ferry ride from Manhattan. The preserve, part of the ancestral land of the Manhanset peoples, covers over 2,350 acres of marshes, fields, woodlands and tidal creeks. Even though it’s practically within sight of the waterfront mansions of the Hamptons, Mashomack is considered one of the healthiest habitats in the Northeast.

After outfitting everyone with camo jackets and optional bright orange vests and beanies (high-visibility gear isn’t legally required for close-range bow hunting), we gathered for introductions. The group wasn’t just racially diverse; we had farmers, lawyers, medical students and tech workers. We talked about our reasons for coming. Everyone wanted to engage with the natural world in a more meaningful way, beyond just enjoying the scenery on a hike. Some wanted to connect more deeply with their food networks, by learning real skills to become more self-sufficient. Others wanted to experience community with like-minded people of color. A few had children and said they couldn’t wait to pass on the new knowledge and appreciation of the environment to their kids.

One thing all hunters are familiar with is early mornings. That Saturday morning was no exception: coffee at 4:15 a.m., out the door by 5:15 a.m. We spent the day in tree stands, getting to know one another and keeping an eye out for deer. No one got off a shot—it was unusually hot, which tends to keep deer out of sight—but that didn’t ruin anyone’s day. Back at the camp house that evening, people shared their experiences: the feeling of a pounding heart upon spotting a huge buck just out of range, or enjoying the sunrise and the stillness of the day.

A longtime Mashomack hunter, Bernard Mini, donated a deer he had killed the day before through the Shelter Island Deer Management Program, which allows some deer hunting to better protect the forest understory. A big part of learning to hunt is learning how to use as much of the animal as possible to prevent waste and show respect to the animals. As the mentors demonstrated how to butcher a deer, I thought how wild it was that people who had never left the walls of a big city were now skinning a deer out on Long Island. As a big foodie, I’m always looking for new wild-game recipes to try dishes like elk andouille sausage and maple-sage venison breakfast sausage. That night I drew on my Louisiana roots and made a big batch of wild-game gumbo with duck, deer and elk sausages and squirrel and geese from hunts earlier in the year.

Nobody wound up getting a shot on Sunday either, but that afternoon we had another butchering session with donated deer, showing mentees how to identify different cuts of meat and how to vacuum-seal it. It was a real hands-on experience; as more than one person pointed out, it was a world away from trying to learn something from a YouTube video. Whether or not people saw an animal or drew a bowstring, it was the experience of being outside, feeling the connection between mentors and mentees, that was the true measure of success.

A crossbow training weekend at TNC’s Hannacroix Preserve was the last mentored hunting event of the year, where 10 new mentees learned how to deer-hunt with crossbows. We’re planning more for 2023, and the waiting list is growing by the month. The Nature Conservancy’s assistance has been crucial from the start, helping with land access, transportation logistics and hunting equipment. The program is already expanding to other states.

Wherever we go, the goal will stay the same: Build a welcoming, diverse and self-sustaining hunting community. Now that mentees have the basics down and their own equipment, they can go out on their own and eventually pass on their knowledge. Some are getting ready to become mentors themselves this year, escorting their own apprentices into the woods and showing them how to hunt safely and respectfully. That way, we’ll complete the circle and create a new wave of hunter-conservationists who will protect the land and continue to bring future generations into the fold.

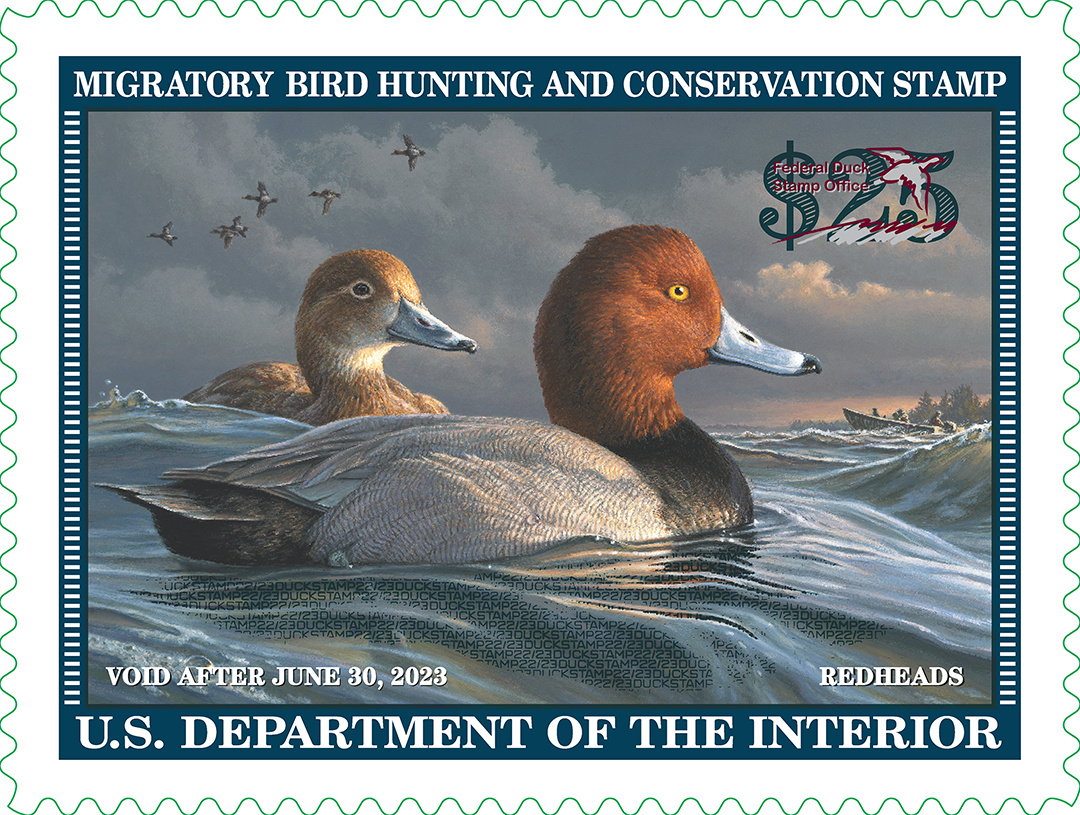

Funding Habitats: The Duck Stamp

For nearly 90 years, one stamp has made an outsized impact on America’s waterfowl. The Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp—popularly known as the Duck Stamp—launched in 1934 as a way to fund the Migratory Bird Conservation Act. That act, passed five years earlier, created a federal commission with the power to approve U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service land purchases critical for birds.

The stamps resemble postage stamps, but they are not for sending mail. They provide entrance admission to national wildlife refuges and are required to hunt birds. Revenue from stamp sales goes toward the purchase of land for the wildlife refuge system. According to the U.S. Postal Museum, income from the stamps has helped conserve more than 5 million acres of waterfowl habitat.

Today the stamps are also collectors’ items. Since the 1950s, an annual art competition has determined the image on each year’s stamp. The dozens of pictures now amount to a catalog of America’s birds and a monument to a Depression-era conservation success.

Magazine Stories in Your Inbox

Sign up for the Nature News email and receive conservation stories each month.