The Movement to Rename Species

The common names of some species have not aged well. These scientists want to change them.

Text by Suzanne Goldsmith | Illustrations by Zoe Keller | Fall 2023 Issue

For Stephen Carr Hampton, the Scott’s oriole is a beautiful bird with an ugly name—so ugly, in fact, that he won’t say it out loud.

Hampton, who recently retired from a career at the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, is an avid birdwatcher and enrolled citizen of the Cherokee Nation—he has traced his ancestry all the way back to the Cherokees’ Constitutional Convention in 1827. After the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and a series of violent raids, Hampton’s forebears were driven out of their homeland in Georgia by the U.S. military. Hampton’s great-great-grandfather, Thomas Jefferson Parks, then 17 years old, drove a wagon that carried his own people to an Oklahoma reservation—part of what would become known as the Trail of Tears. The architect of that cruel process was General Winfield Scott, who had also played a role in the U.S. military effort to push the Seminole out of Florida. Under orders from President Martin Van Buren in 1838, Scott oversaw the brutal campaign to force around 60,000 members of the Cherokee, Muscogee, Seminole, Chickasaw and Choctaw nations from their ancestral homes to lands west of the Mississippi. The forced march and relocation killed thousands, and many more faced starvation, exposure, exhaustion and disease after their arrival.

In 1854, a U.S. Army officer named Darius Couch observed a striking black-and-yellow desert oriole. The bird already had a scientific name: Icterus parisorum. But it had no common name—the name most people use informally to refer to a species—so Couch called the bird “Scott’s oriole,” after his commander, Winfield Scott. Three decades later, when the American Ornithological Union published its first checklist of common English bird names, Scott’s oriole became official.

Today, Hampton can’t stomach the name. “There are other Indian-killer bird names, such as Abert’s towhee, Clark’s nutcracker and Couch’s kingbird, or Indian-skull collector names like Townsend’s warbler and Townsend’s solitaire,” Hampton wrote in a blog post in 2021. “It’s hard to be a Native birder in the West and not run into these. But nothing irks me like Scott.” He wants that name changed. And many others agree with him.

The case for changing the common names of animals

In the summer of 2020, amid a nationwide reckoning over race in the United States, 182 birders and ornithologists petitioned the American Ornithological Society to remove all bird names that contain “significant isolating and demeaning reminders of oppression, slavery, and genocide.” But it’s not only birders looking for change. The petition was one of several events that accelerated a broader debate over what to call the plants and animals around us—and what and who we choose to honor and commemorate.

The naturalist community has raised a variety of issues with species common names. In some cases, a name simply doesn’t describe an animal very well. In others, as with Scott’s oriole, a legacy of brutality and ethnic cleansing is forever attached. And in still others, where an animal or plant is an invasive species conservationists want eradicated, some fear names that reference foreign countries or ethnic groups could promote xenophobia.

Many of those asking for change argue that these names discourage people from entering the natural sciences or from taking pleasure in nature—often the first step to becoming a conservationist. Their efforts are not proceeding without challenges and accusations of political correctness. But despite pushback, it seems clear that in the coming years, many birds, fishes, insects and places will come to be known by new names.

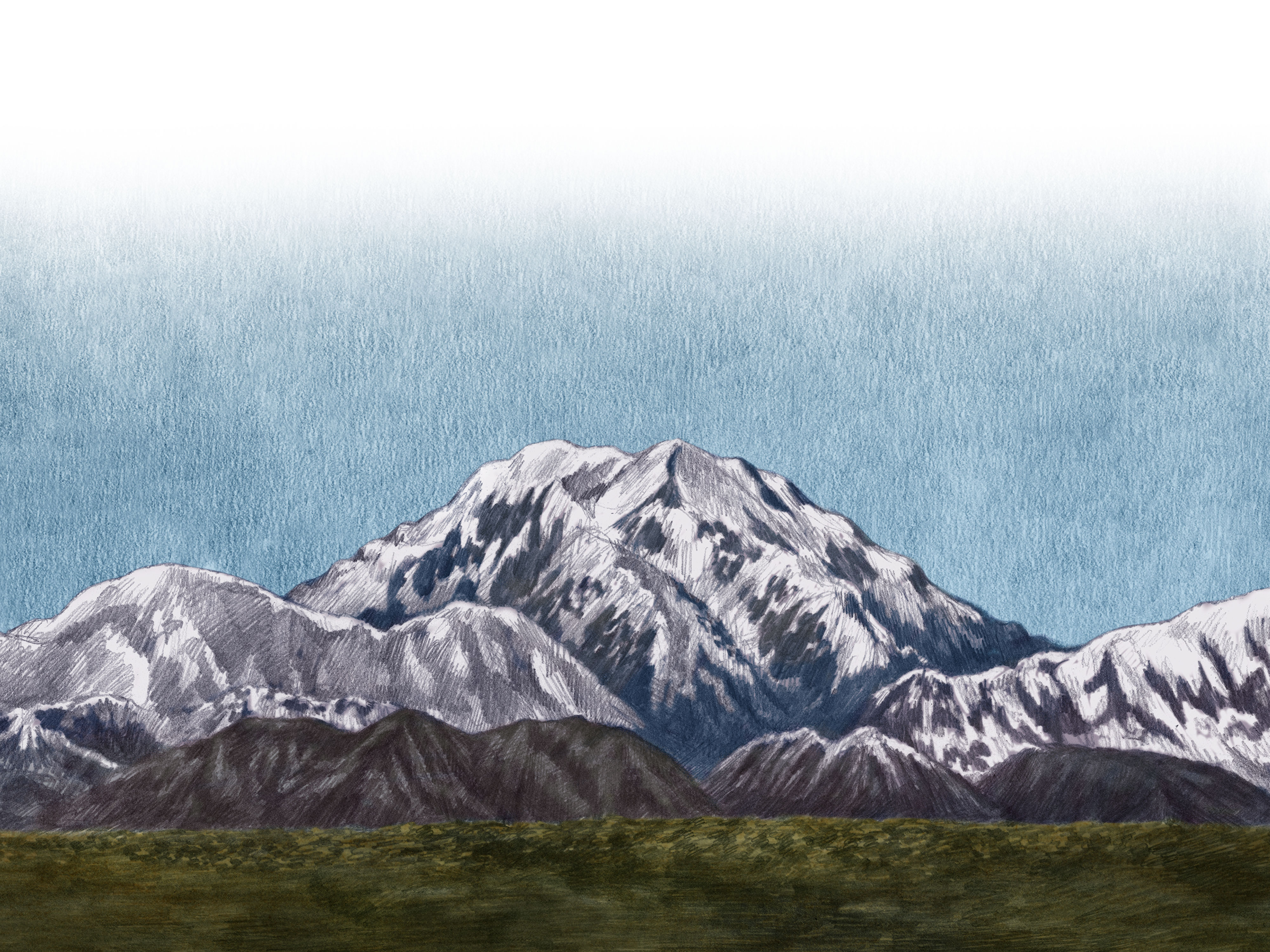

Denali

This Alaska mountain was called Mount McKinley for more than a century. In 2015, its official name became “Denali,” after a traditional Koyukon Athabascan term meaning “the tall one.”

Why some species are renamed

In the world of animal species, scientific names (often in Latin) are regulated by the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature and are usually changed only for taxonomic reasons, such as when a species is subdivided or reclassified. Less than a decade ago, for example, scientists discovered that there were four genetically distinct giraffe species—not just one—and their scientific names changed accordingly. But common names vary from country to country and language to language. They are often certified by regional groups and societies, such as the American Ornithological Society and the Entomological Society of America, which can also change names when deemed appropriate.

Changing official common names isn’t new. We no longer have a grouper called a “jewfish,” for example. It’s the push for a broader, more proactive approach and a deeper dive into the history of names that is gaining ground now. In 2021, the Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists changed the name of its quarterly journal, called Copeia in honor of Edward Drinker Cope, a 19th-century scientist who also produced racist and misogynistic writings. Similarly, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service stopped using the term “Asian carp” in official documents in favor of “invasive carp” for the troublesome fish that advocates are trying to keep out of the Great Lakes.

Place names, too, are being scrutinized. In September 2022, the U.S. Department of the Interior announced it would change the names of more than 600 places that contained the word “squaw.” Often used as a slur by white settlers for Indigenous women, the term’s meaning has ranged from “woman” to more demeaning references to “loose women.” In a statement announcing the change, Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, a member of the Laguna Pueblo tribe, said, “Racist terms have no place in our vernacular or on our federal lands.”

In 2021, Squaw Mountain in Colorado was renamed Mestaa’ehehe Mountain—“Owl Woman”—following efforts by representatives of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes. Once a slur, the mountain now honors an Indigenous woman.

The impact of a name that offends can be far-reaching, says Leigh Greenwood, North American forest pest and pathogen program director for The Nature Conservancy. Greenwood, whose work often involves promoting the control or eradication of invasive species, recently helped petition the Entomological Society of America to change the name of the leaf-munching invasive then known as the gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar). Its former name contained a pejorative term for the Romani people, Europe’s largest ethnic minority group.

Greenwood says scientists depend on the public to assist in the control of pests. “The vast majority of invasive species are found not by formalized systems, but instead by interested members of the public,” she says. “We don’t want to alienate anyone in the world of science.”

This issue was on entomologist Chris Looney’s mind when, in late 2019, he learned that a newly discovered invasive hornet in his home state of Washington was being referred to both as a “murder hornet” and an “Asian giant hornet.” The species is indeed fearsome, with a habit of decapitating whole hives of honeybees. To stop its spread, Vespa mandarinia was targeted for eradication in North America in summer 2020.

But Looney, who works for Washington’s Department of Agriculture, says the insect’s name was problematic for many reasons. Calling it a murder hornet “stoked entomophobia,” creating overly dramatic headlines and panic. And since most hornets originate in Asia, calling it the “Asian giant hornet” wasn’t very specific. Indeed, entomologists got a late start on eradicating this invasive, Looney says, because one of its earliest sightings was reported as an “Asian hornet,” the common name used for a different invasive species (Vespa velutina).

And there was an additional problem: In 2020, amid a climate of fear over COVID-19, which had originated in China, hate crimes against Asian Americans were on the rise. Looney and others, including Greenwood, worried about unnecessarily attaching the “Asian” moniker to a bug that was being dramatized as a “murder hornet” in the news.

In June 2021, the Entomological Society of America launched a solution: The organization’s new “Better Common Names Project” set out to identify and change “names that contain derogative terms, names for invasive species with inappropriate geographic references and names that inappropriately disregard what the insect might be called by native communities.” The project took up the issue of the moth, Lymantria dispar, and in March 2022, the “gypsy moth” became the “spongy moth,” in reference to its egg mass.

In May 2022, Looney petitioned the society to name the hornet the “northern giant hornet,” referring to its native range in the northern parts of Asia. He cited the need for clarity, accuracy and cultural sensitivity. The society accepted the petition and renamed the hornet two months later.

The ongoing logistical challenges of changing the names of species

Changing names has not always gone so smoothly, though, and resistance has perhaps been most heated in the birding community, where many common names refer to historical figures. In 2018, the American Ornithological Society rejected a proposal to change the common name of McCown’s longspur (Rhynchophanes mccownii), which is named after a general in the Confederate Army. That proposal, written by then-graduate student Robert Driver, likened the name of the bird to a statue glorifying the general and argued that it should be removed, just as many Confederate monuments were being removed throughout the South at the time.

Two years later, in the summer of 2020, the issue came to a head. That May a video captured a white woman harassing a Black birder in New York City’s Central Park. It launched a broader discourse about racism in the birding community, and in response, Maryland ornithologists Jordan Rutter and Gabriel Foley created Bird Names for Birds, an initiative to rethink bird names, especially those that memorialize people.

The group came to a simple but far-reaching conclusion: Rather than judging the moral worth of each bird’s namesake, they said, the American Ornithological Society should eliminate all eponymous bird names. Why not adopt names— like red-winged blackbird—that will help fledgling birders identify them, Rutter says. The group filed a petition to the Society with more than 2,500 signatures that summer.

In August 2020 the American Ornithological Society reversed its decision on McCown’s longspur and renamed the bird the thick-billed longspur. In a subsequent online gathering, most ornithologists and bird lovers agreed that it was time for the Society to revisit at least some eponymous bird names—two of the nation’s top bird-guide authors, David Sibley and Kenn Kaufman, spoke in favor of reconsideration. But disagreement over how far to take the efforts is also evident.

James Van Remsen, a retired ornithology professor at Louisiana State University and a member of the American Ornithological Society committee that approves name changes, opposes eliminating all 145 or so honorific bird names as too cumbersome. Instead, he says, a dozen or so of the most egregious names should be changed.

Van Remsen says other birders agree but are afraid to speak up. “They like knowing something about the origin of the bird and its discovery,” he says. “Of all the things that we could do to make up for some of the brutality of that era, changing bird names seems to a lot of people to be way down the list.”

The diversity of views was apparent earlier this year when the National Audubon Society considered and then declined to rename itself. (Its namesake John James Audubon owned enslaved people.) In response to the decision to keep the name, three members of the organization’s board resigned.

As birds, fish, insects and places take on new names, the debate over how to handle history and cultural sensitivity isn’t slowing down: The Entomological Society’s Better Common Names Project now accepts public submissions. The American Ornithological Society has tasked a committee with developing recommendations for how to handle renaming birds. In the meantime, though, the Scott’s oriole remains as is. Stephen Carr Hampton has suggested a new and less-charged name in honor of its habitat: the yucca oriole.

Editor's Note:

The American Ornithological Society announced on November 1, 2023, that it plans to change the English common names of all American birds named after people as well as other names deemed offensive or exclusionary. The process will begin in 2024 and will focus initially on 70 to 80 birds found in the U.S. or Canada. New names are expected to describe characteristics of the birds themselves.

In a statement announcing the decision, Society executive director and CEO Judith Scarl said, “As scientists, we work to eliminate bias in science. But there has been historic bias in how birds are named, and who might have a bird named in their honor. Exclusionary naming conventions developed in the 1800s, clouded by racism and misogyny, don’t work for us today, and the time has come for us to transform this process and redirect the focus to the birds, where it belongs.”

Magazine Stories in Your Inbox

Sign up for the Nature News email and receive conservation stories each month.

About the Creators

Illustrator Zoe Keller was commissioned to create these illustrations for Nature Conservancy magazine. Based in Maine, Keller specializes in graphite drawings and digital media portraying the natural world.

Writer Suzanne Goldsmith is based in Columbus, Ohio. She is the author of two books and is a former editor for Columbus Monthly.