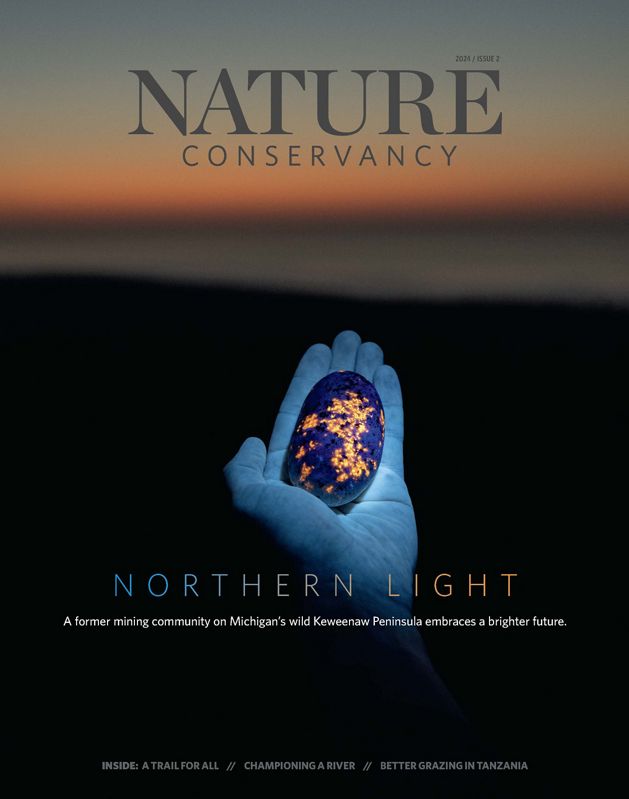

Swamp Glow Spanish moss, lit with color-gelled flash, hangs from cypress trees along the Suwannee Canal on April 12, 2023 inside the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge. © David Walter Banks

Editor's Note

During summer 2025, The Conservation Fund announced that it will purchase the titanium oxide mine that planned to open just outside the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge. That’s 8,000 newly protected acres!

Nothing prepared me for the quiet of Georgia’s Okefenokee Swamp. I am from Florida, where I learned to associate swamps with the roar of airboat engines. But on this April day near the Florida-Georgia border, it’s so still I can hear the low whistle of every breeze passing through the Spanish moss-draped cypress trees that tower over the water’s edge. The only other sound is that of our paddles swishing the water as my 16-year-old son Luke and I propel our little green rented canoe into the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge. All around us, the still, black water perfectly reflects everything in view, creating a dreamy effect where the trees, sky and clouds appear above and below us.

“This is amazing,” Luke quietly says to himself.

He rests his paddle across his knees and tilts his head back to take in the sight. I do, too. Staring up at this cathedral of cypress, it’s incredible to think that the fate of this place—the largest blackwater swamp in America—is so up in the air. The Department of the Interior is considering whether to nominate it for inclusion on the UNESCO World Heritage Site list, which would recognize Okefenokee as a natural place of international significance. On the other hand, it also might be irreparably damaged by a proposed titanium dioxide mine that just moved closer to approval by the state.

We begin paddling again. Our canoe sits low in the water, loaded with sleeping bags, hammocks, camera gear, bug nets, way too much food, just enough drinking water and a map that has already become soaked.

We aren’t the only ones here. About 100 feet farther, we spot an alligator near a grassy bank—and it spots us. Most of its motionless body floats underwater. Its head is bigger than a piece of carry-on luggage, and its craggy back looks like a sunken tree trunk. Luke and I instinctively freeze as we glide past the attentive gator less than 20 feet away.

“I’ll name him Mr. Pinchy,” I joke to lighten the mood. The next alligator is much smaller—only about 4 feet long—and it silently slips underwater the moment we spot it. I name that one Nibbles.

Alligators are the obvious animal celebrities of any Southern swamp, but it’s not an easy life. We pass a small tour boat and overhear the captain explain the local dynamics: The refuge doesn’t use hunting to manage the alligator population here because when the animals start to crowd one another, the larger gators eat the smaller ones. Suddenly, I understand the differing attitudes of Nibbles and Mr. Pinchy: One gator is working to stay off the lunch menu, while the other—at the top of the local food chain—has all options on the table.

We turn south off the main canal and paddle down a narrow boat path with signs toward Chesser Prairie and Monkey Lake, the spot where we reserved a campsite for the night. Here the cathedral canopy of cypress opens onto a miles-wide stretch of water—covered in lily pads and dotted with islands that range from a few square feet to many acres. We’ve entered the heart of the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge. It’s one of the wildest places I’ve ever visited—and it’s the source of boiling tension over the desires of industry and the need to protect one of the least-developed places in the United States.

About the Photography

Photographer David Walter Banks spent at least 30 nights in the Okefenokee in the past few years capturing images of the swamp. To convey the land as he sees it—full of life, movement and biodiversity—he experimented with colored filters placed over his flash units. He also used long exposures, double exposures, flashes and more.

How the Okefenokee became “land of trembling earth”

The Okefenokee Swamp serves as the headwaters for the Suwannee River, which runs all the way downriver to the Gulf, and the St. Marys River, which flows to the Atlantic. The main trail that we have been traveling is a canal that was originally dug in the 1890s by a company that planned to drain the Okefenokee Swamp and connect the two rivers. The venture failed, and in doing so, it allowed what is now believed to be the largest undamaged peat swamp in Earth’s temperate zone to remain intact.

Archaeological evidence shows human activity in the swamp starting about 4,500 years ago. It is believed that numerous Indigenous communities inhabited the area for millennia. Spanish missionaries arrived in the 1600s, and white settlers lived in or around the swamp starting in the 1800s, surviving as hunters and loggers and receiving deeds from the U.S. government. By the mid-1800s, federal and state militias had driven many of the Seminole inhabitants out of the area.

Quote: Luke Seeger

I always imagined swamps to be these big dead places where nothing could survive. But I’ve never been somewhere more alive than here.

In the early 1900s, writers and naturalists who visited the swamp advocated for the protection of the Okefenokee from logging and development. The refuge was established in 1937 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt during the New Deal era. The national wildlife refuge protected important wintering grounds for migratory birds while establishing a work area for the Civilian Conservation Corps’ program to create reliable jobs during the Great Depression. In the late 1970s, The Nature Conservancy donated more than 14,000 acres of land to expand the refuge. Today, it spans about 400,000 acres, covering more than 90% of the swamp.

The word “Okefenokee” translates from the Creek Indian language as “land of trembling earth,” and it’s not hard to see why: We paddle by many unstable peat islands along the canoe trail. The smaller ones have the consistency of a wet sponge. They shake or squish underfoot.

The peat in these tufts of ephemeral land gives the water its dark tannins and distinct coffee color. Bread loaf-sized clumps of peat float by our boat. Up close, peat looks like dead leaf matter that has been pulverized into a coarse, wet dust. Luke keeps trying to catch some with his paddle, but the clumps immediately dissolve into underwater clouds at the slightest touch.

Make Your Voice Heard

Learn the latest news on the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge and find out what you can do to help here.

All the dead organic matter in the Okefenokee’s peat locks up an estimated 140 million metric tons of carbon, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. That’s the equivalent of the carbon dioxide produced by burning 50.4 billion gallons of gasoline. Per acre, the Okefenokee is one of the largest natural carbon storage systems in the United States. Wet peat decomposes very slowly, retaining its carbon. But peat breaks down when exposed to air, releasing carbon dioxide in the process.

According to Michael Lusk, manager of the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge, the swamp receives about 80% of its water from rainfall. Some of that water leaves via the Suwannee and St. Marys Rivers, but much of it is kept in the swamp by Trail Ridge. This geological formation on the east side of the Okefenokee is often described as the edge of a large sand “bowl” that creates the swamp’s near-surface aquifer. Under that water sits a layer of clay and limestone and the deeper Floridan aquifer.

In 2019 land managers, conservationists, scientists and citizens became alarmed when a company called Twin Pines Minerals proposed an expansive titanium dioxide mine on top of Trail Ridge, less than 3 miles from the boundary of the national wildlife refuge. The company’s draft permit from the state’s Department of Natural Resources Environmental Protection Division would allow it to draw 1.44 million gallons (equal to more than two Olympic-sized swimming pools) per day from the Floridan aquifer.

Water levels inside the refuge naturally fluctuate in relation to rainfall, Lusk says. And during extreme droughts, much of the swamp can become dry, creating an opportunity for wildfires that are ignited by lightning strikes and can feed off the highly flammable dry peat. The fires can continue smoldering underground for weeks or more until normal water levels return. It’s part of the swamp’s natural cycle. But Lusk is concerned that permanently lowering the swamp’s level would increase the frequency of fires, disrupt the swamp’s ecosystem and dry out the peat, releasing some of the carbon it currently stores.

In letters to the Georgia Environmental Protection Division, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service outlined potential problems posed by the mine’s water needs—and reasserted the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge’s federal water rights. The Nature Conservancy and a long list of conservation, environmental and science groups in Georgia have voiced grave concern that if the mine moves forward, it could have devastating effects on the swamp.

Despite those concerns, the Georgia Environmental Protection Division in early 2024 issued draft permits to Twin Pines Minerals, moving one step closer to approving the mine. If it does so, the proposed mine may only be the start of a larger operation near the swamp. “Our concern is that Twin Pines has indicated multiple times that they have no intention of being limited to this one small-scale pilot project,” says Michael O’Reilly, TNC’s director of policy and climate strategy in Georgia. The company’s various plans have sought to mine on 12,000 acres that reach within 500 feet of the edge of the Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge.

In 2023 and 2024, a bipartisan majority of lawmakers in the Georgia state house of representatives supported legislation to protect the Okefenokee Swamp, but the bill never reached the house floor for a vote. O’Reilly anticipates that legislation will be introduced again in 2025 if plans for the mine continue to move forward.

“I’ve never been somewhere more alive than here”

After six hours of paddling, we arrive at our reserved campsite in the southeastern corner of the refuge, a secluded spot called Monkey Lake. There’s a small dock with a composting toilet. A 100-foot-long boardwalk leads through a forest of cypress trees and thick bush to a covered wooden deck big enough for a picnic table and some tents.

Luke sets up our hammocks and bug nets while I start cooking dinner on our little camp stove. Earlier that day at the outfitters shop we were warned that the mosquitoes come out in droves right before dusk. So we button our shirts up, roll down our sleeves, pull up our socks and cover any exposed skin in insect repellent. Just in time, too. Once the sun gets low, mosquitoes show up in quantities rivaling a Bible story’s plague of locusts.

This will be the beginning of one of the loudest nights of our lives.

As the sun sets, the birds around us start singing, tweeting and calling in numbers that I’ve never heard before. Like any self-respecting teenager, Luke whips out his iPhone to record the sounds. It’s an absolute cacophony of owls, hawks, wading birds, cranes and dozens more smaller birds all at once.

By the time dusk has settled into darkness, the bird calls are overtaken by the croaks of frogs—thousands and thousands of them. Luke walks up and down the wood-plank walkway to the dock enthralled by a curious phenomenon: The din of the frogs gets louder wherever he stands. By 11 p.m., the frogs go quiet. In their silence, we hear a low hum that vibrates across the landscape—millions of mosquitoes working the night shift. We marinate ourselves in insect repellent once more, double-check the bug nets on our hammocks and nod off to mosquito-generated white noise.

An hour before sunrise, we are awakened by the sound of birds again. By 8 a.m., the birds quiet down, the mosquitoes go away and the Okefenokee becomes tranquil again.

“I always imagined swamps to be these big dead places where nothing could survive. But I’ve never been somewhere more alive than here,” Luke muses as he packs our gear and I cook breakfast. “Everywhere we’ve gone in the Okefenokee, we’ve been surrounded by animals. Something is always watching us.”

Almost on cue, the low bellow of an alligator probably 50 feet beyond the trees that surround our campsite startles us into silence. It has the deep baritone of a lion. This bellow is matched by two more nearby alligators, each rumbling louder than the last. (I later learn that these could be mating calls or territorial claims.) Luke once again grabs his phone to record the sounds to share with his friends when he gets back home.

During the day’s paddle back, we are amazed at the life around us. We count five different colors of dragonflies. We notice hundreds of carnivorous plants—pitcher plants and bladderworts busy digesting meals of insects. We cheer for some little green anole lizards as they scramble and swim from one lily pad to the next, evading hungry fish.

I’m struck by something Lusk, the refuge manager, said to me earlier. “This is what [a healthy swamp] is supposed to look like, how it’s supposed to function. And that’s what makes it so unique,” he said. “It is worth protecting.”

As a magazine editor, I have worked on articles about efforts to repair Florida’s Everglades and the Great Dismal Swamp in North Carolina and Virginia. The former is polluted with runoff and invasive species, and the latter is a fraction of its original size. Both swamps were dredged, channeled and drained to accommodate a variety of industries, but now they are the subjects of long, expensive work to restore their broken hydrology and ecosystems. Those projects cost hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars every year. Right now, the Okefenokee needs none of those restoration efforts.

On our drive home, I can’t stop thinking about our night in the swamp and the threats facing this unspoiled spot. Luke, in the passenger seat of our minivan, focuses on his phone, typing messages in a group chat. It’s the classmates from his school’s camping and boating club. “I’m telling them about our trip,” he says as his thumbs tap the screen, “and I’m trying to see if we can do a trip to Okefenokee in the future. They need to see that place.”

“Yeah,” I say. “More people do.”

About the Creators

David Walter Banks is an Atlanta-based photographer. His work has appeared in The New York Times, National Geographic and many other publications.

Eric Seeger is the deputy editor for Nature Conservancy. Based in Asheville, North Carolina, he has written and edited for magazines since the late 1990s.

Magazine Stories in Your Inbox

Sign up for the Nature News email and receive conservation stories each month.