Unleashing Rivers

New England’s waterways—the most heavily dammed in the United States—are making a comeback.

December 2016/January 2017

Sally Brown knows how to throw a party. On the second floor of an old mill factory in rural New Hampshire, she gathered several friends to watch a dam—her dam—be removed from the Ashuelot River. “It was very exciting,” she recalls a few years later. “We had sandwiches, iced tea. We had a regular picnic while we watched it. A little removal party for that damn dam.”

The dam, on a tributary of the Connecticut River, had once powered a textile factory known as Homestead Woolen Mills but had become a thorn in her family's side. Brown inherited the complex from her late husband in 2008. His family had run the mill since 1911, the flow of the river powering the mill until electricity took over. Previously it had powered a 19th-century box-making factory across the river. The dam had stood there, Brown jokes, "since God created Earth." As long as it stood, fish were able to migrate through this part of the river.

In its heyday, the Brown family’s textile mill employed 500 people. Wool from West Texas, New Zealand and Australia arrived by the baleful; workers washed, dyed and spun it before sending the bolts of material to a shop on Seventh Avenue in Manhattan. There it was turned into women’s clothing, military uniforms, Catholic schoolchildren’s skirts and blazers, and even army blankets during World War II.

The textile market eventually dried up as overseas manufacturing became cheaper, and the mill closed in 1987. The 140-foot-long dam, made of wood timbers and piles of Granite State rocks, fell into disrepair and became a liability. It would take at least $1 million to fi x it; less to remove it. The Browns turned to state agencies for help, and the long removal process began.

On the day of Sally Brown’s picnic, a rainy day in August 2010, an excavator took a bite from the dam. Water rushed through. And for the fi rst time in more than 200 years, 365 miles of the Ashuelot River and its tributaries ran undisrupted. Brown, her friends and several partners involved in the removal smiled and toasted with their glasses of iced tea. It had taken 12 years for the group, which included The Nature Conservancy, to reach that moment.

The headache might be over for Brown, but the work continues for partners from the state and other organizations that are trying to reopen rivers in New England. This region has some of the most densely dammed rivers in the country, and restoring fl ows here means repeating the victory at Homestead Woolen Mills many times over.

More than 14,000 dams dot the New England landscape. Most are small—less than 12 feet high—and have existed for a century or two. Now relics of the Industrial Revolution, they were once engineering feats, using the force of rivers to spin water wheels and turbines to power sawmills, textile mills and grist mills.

To understand the physical eff ects of the Industrial Revolution on the landscape of New England, you need only look to the region’s skyline, says Jamie Eves, director of the Windham Textile and History Museum and a mill historian. Old smokestacks rise over towns that had grown up around the mills. The artifi cial ponds formed by dams attract home buyers looking for property with a water view. Even after mills close, many towns hold on to the dams that powered them. “It’s more than nostalgia,” says Eves. “It’s economic—and identification with a cultural heritage.”

The manufacturing sector left behind an enormous industrial mess. Before the federal Clean Water Act of 1972 mandated changes, fumes coming from polluted waterways in New England peeled the paint off riverside homes. At one mill in Connecticut, Eves says, textile workers dumped the day’s leftover dye into the river. Residents knew what day it was based on the color of the water.

That’s all changed now. The ecological problems in the rivers have less to do with pollution than with connecting disparate habitats. The density of dams in New England means that fish habitat becomes truncated, spawning migrations are altered, and, in summer, water temperatures rise and oxygen levels drop because of slow river flows. In the past five years, state agencies and nonprofits, including the Conservancy and American Rivers, have increased their efforts to unclog the rivers.

That is Steve Gephard’s specialty. A fisheries biologist with the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection, he has spent 35 years restoring native runs of salmon, shad and other fish that migrate upriver from the ocean. “When I first started, there were three fishways in the state of Connecticut and no dam removals,” he says. “Now people who would never have dreamed of removing a dam are [doing so].”

Connecticut’s remaining 4,000-plus dams pose a fairly simple problem from a fish perspective: Most fish species migrating upstream simply can’t jump high enough to cross even a small dam and so can’t reach the habitat on the other side. Less habitat means fewer fish.

Not every dam can or should be removed, Gephard is quick to say. He and his partners at The Nature Conservancy and American Rivers try to be strategic when selecting dams to be removed.

In 2011, a multi-agency partnership finished a four-year effort in 13 states to map and identify dams where removal would provide the greatest benefit, including the entire Connecticut River watershed. The river dominates New England, running 410 miles through four states and powering dozens of hydropower facilities along its main stem and tributaries. Its tributaries sprawl from the Quebec-New Hampshire border to Long Island Sound. On average, a dam stands every 10 miles on its waterways. “You’ve got more than 2,700 documented dams in [the watershed],” says Kim Lutz, the Conservancy’s Connecticut River program director. “You don’t want to spend your time unwisely.”

The Conservancy built a database of dams to prioritize where to begin. The partnership designed software that helps everyone focus on the dams whose removal could have the greatest benefits for migratory and resident fish and the river itself. “It looks at things that you might think are pretty obvious, like how many river miles are connected,” says Lutz, adding that it also considers how many obstructions exist downriver from a given dam. This process helps identify the barriers that—if removed—will provide the best results for the river.

A similar effort has developed in Maine’s Penobscot River watershed, where the state and federal agencies, the Conservancy, and other nongovernmental groups are mapping dams and culverts on thousands of streams. After removing two major main-stem hydropower dams and building a fish bypass on a third—part of a historic $64 million agreement signed by the Penobscot Indian Nation, five nonprofits, and state and federal agencies in 2004—new analysis on tributaries is helping partners focus on opening additional habitat for the annual migrations of sea-run Atlantic salmon, river herring, sea lamprey, shad and American eel.

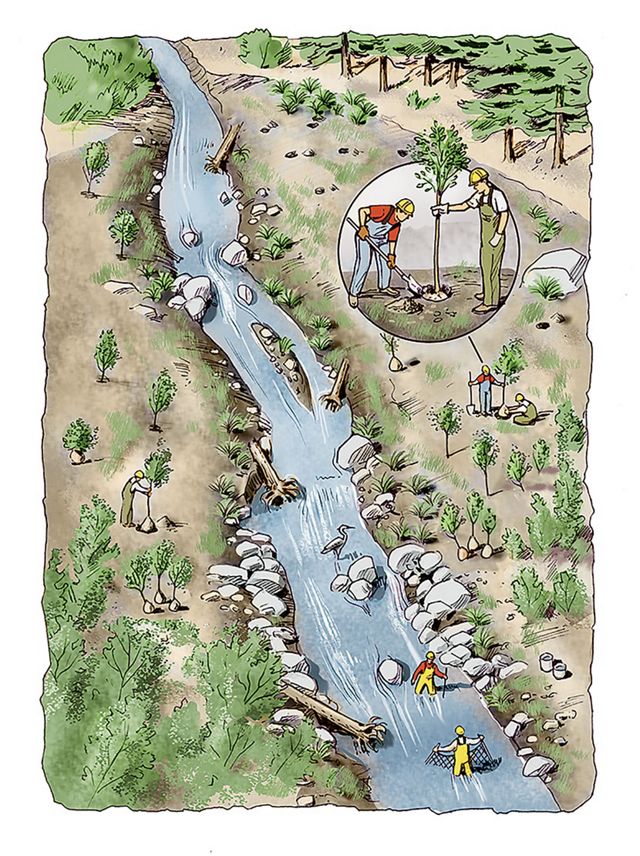

Reconnecting parts of the Penobscot’s main stem made nearly 2,000 miles of river accessible from the Atlantic. Before the dams were removed, fish migrating from the ocean were limited to just over 30 miles of navigable river. Dams have altered food webs throughout these systems, even affecting coastal cod and halibut fisheries in the Gulf of Maine, according to Joshua Royte, a conservation scientist for the Conservancy in Maine. And for decades, fish have been bred in captivity and trucked upstream. With the removal of barriers in the Penobscot, the fish are coming back. Past counts of just a few thousand river herring have blossomed to more than 1.8 million in 2016. Researchers also documented three short-nosed sturgeon swimming farther upriver than they’ve been seen in 200 years. The focus now is on removing smaller dams and impassible road culvert crossings in the river’s headwaters, which biologists hope will continue to increase the numbers of fish. “We need to start healing the thousand little cuts to the headwaters,” Royte says. As more good habitat becomes accessible for spawning and rearing, he expects the fish populations to continue to grow.

Dam removals and modifications along the Penobscot River have become an example that Conservancy staffers cite when advising developing nations that want to increase their hydropower supplies. “We use the Penobscot as a powerful example because they came up with a solution where the overall [hydropower] system will produce as much energy as it did before dam removal. But by making the right choices of what dams stay and what dams are removed, they transformed how [the river] works for fish,” says Jeff Opperman, who as lead scientist for the Conservancy’s Saving Great Rivers Program gives strategic advice to international hydropower developers. “For other countries, the challenge is to get it right the first time. Countries that are just now building dams have the chance to find that right solution—like they ultimately came to at the Penobscot—the first time around.”

Along the Connecticut River through interior New England, the broad success of the Penobscot’s mainstem agreement feels far away but not impossible. More than 2,700 dams clog the river and tributaries. But those decrepit barriers are slowly becoming fewer and farther between, says Amy Singler, a Massachusetts-based river ecologist who works for both American Rivers and the Conservancy.

Singler has been working on rivers for 16 years. She’s a fast talker, jumping between projects and the two organizations she works for. “Dozens of projects are going on across New England,” she says. This year in Connecticut, seven dams have been removed, including Conservancy-led projects on Jeremy River and East Branch Eightmile River.

Part of that momentum has come from new dam safety legislation that gives owners reason to repair their dams or remove them entirely. Owners are typically required to ensure some level of safety on their property, but bills passed first in Massachusetts and more recently in Connecticut have made owner liability a heavier burden. If a dam fails, owners are on the hook for damages. “For dam owners, they’re saying this is a liability,” says Singler. Not only that, but the cost of getting dams regularly inspected—required by state law—has gone up.

Owners are also realizing that the dams and artificial ponds they grew up with aren’t as natural as they seem, says Singler. “Ponds have to be dredged, dams have to be taken care of,” she says. But once her work is done, it’s done—no maintenance required. “We’re restoring the function of an ecosystem. That’s what’s really exciting: Rivers are self-healing.”

Mussels now hitchhike upriver attached to fish, adding nutrients for other upstream species. As alewives return, the fledge rate of ospreys goes up. As artificial ponds transition back to free-flowing water, owls, raccoons, otters and other animals benefit from the improved fish runs. “All of these things are sitting at the smorgasbord,” Gephard says.

It’s that self-healing aspect that keeps biologists going in the face of the thousands of dams yet to be removed. Gephard remembers a fish passage he installed in Connecticut 15 years ago: Last year 90,000 fish were counted traversing the dam, up from a just few dozen tallied at the time the passage went in. Singler recalls a river in 2014 where sea lampreys were found spawning just six months after she helped remove a dam.

These days Sally Brown no longer worries about her old dam on the Ashuelot. Six years after the removal party, Homestead Woolen Mills is being overhauled. Brown sold the mill buildings to a developer last year, and she spent the following fall sifting through photographs and documents—deciding, like so much of New England, what elements of the Industrial Revolution she wanted to keep. She’s out of the mill business entirely and ready to retire.

As for the dam, she’s glad to be rid of it. Photographs and memories will be enough.