Five Ways Conservation Keeps Wildlife Moving

By protecting animal migrations and movement, we can build a healthier, more resilient planet.

Eight innovative ways scientists are mapping migrations to make smarter conservation decisions.

Across the sky, over land, through rivers and across oceans, animals are constantly on the move: traveling to find food, water, shelter and mates. And for centuries, people have watched these migrations, timing their hunts, crop cycles, travels and cultural moments to their rhythms.

But there's been a major shift in recent years. Tracking and mapping migrations used to require a person observing on the ground. Now, technology allows us to track migrations with incredible granularity and at massive scales—using satellites, radar, acoustic sensors, eDNA, GPS tags, artificial intelligence and millions of aggregated human observations. From activity monitors on fish to tiny radio tags on insects, many of these solutions are just flat-out cool.

By protecting animal migrations and movement, we can build a healthier, more resilient planet.

But why do we need all this data? What's the point of knowing exactly where a herd of elephants is on any given Tuesday, or mapping the flight paths of hundreds of monarch butterflies?

Well, to protect animals and ecosystems—and the communities that depend on them—we need to understand how wildlife migrate, and how these journeys are changing.

Here are eight innovative ways scientists and decision makers are turning migration data into conservation action.

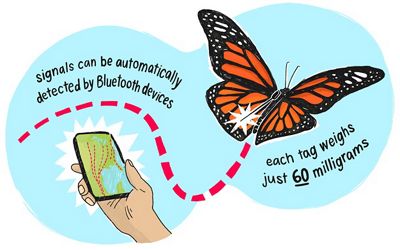

Every fall, monarch butterflies begin one of the longest insect migrations on Earth, traveling thousands of miles from the U.S. and Canada to a small cluster of mountain forests in central Mexico. Scientists track this migration using decades of community-science observations—and recently, tiny solar-powered radio tags.

Video: Cultural Connection

As data points are captured and layered onto maps, patterns emerge. Scientists can identify and research migration pathways, critical breeding and overwintering habitats, and monitor population declines. Conservation groups and land managers then use this information to understand where milkweed restoration will matter most, which forests are essential to protect, and how climate change is shifting migration timing.

→ Explore how monarch migration data guides cross-border conservation.

Stay connected to nature with conservation stories, local opportunities & more.

Many migratory birds travel at night, moving through the sky largely unseen by human observers. One way to track these invisible journeys is bioacoustics—deploying solar-powered recording units that capture the short flight calls birds make as they migrate overhead. By analyzing these recordings, sometimes using AI, researchers can identify which species are passing through, when migration peaks occur and how different landscapes serve as nocturnal flyways and stopover zones.

Video: Partnership Success

When these acoustic data are mapped over time, they help conservationists pinpoint habitats that are critical for migration and better understand how bird communities change over time. On a larger scale, scientists also use a tool called BirdCast that is informed by weather radar data to detect bird movement across entire regions, providing a complementary, big-picture view of migration intensity. Together, listening on the ground and scanning the skies help guide habitat protection and reduce risks birds face during night migration.

→ Discover how scientists track a night-time river of birds.

Like people on a long journey, migrating birds need specific places and moments to rest and eat. Ideal stopover points are getting harder to come by, and this is especially true for shorebirds—nature's ultra-marathoners, with some species migrating thousands of miles. Climate change is eroding the coastal habitat and drought is shrinking already diminished inland wetlands.

TNC scientists in places like California identify these key stopover points by combining satellite imagery and on-the-ground observations from community scientists paired with data from NASA sensors that tells us how birds move across landscapes and where they’re likely to land. When scientists put all this information together, they see something surprising. Some wetlands are critical for only a few weeks a year—and some agricultural fields could become stopover points during droughts or peak migration times.

While it would be impossible to buy every parcel of land along the migration routes, conservation groups use this data to decide when and where to “rent” habitat. Paying farmers to flood their fields and create the temporary wetland habitat only when shorebirds need them for migration stopovers delivers benefits to both farmers and birds.

→ See how migration data drives smarter habitat investments.

For generations, mule deer have followed seasonal migration routes across the American West. With mule deer populations declining across the region, wildlife biologists set out to better understand migration routes and identify trouble spots using GPS collars.

The collars record precise location data multiple times a day. When those data points are layered together, clear migration corridors emerge, including narrow bottlenecks where deer face risks such as road crossings, fences and development.

Alongside partners, TNC’s teams are using the data to find and remove obstacles along migration routes and protect critical habitats.

→ See how GPS tracking is shaping wildlife crossings in Wyoming.

Sign up for Nature News:

Stay connected to nature with conservation stories, local opportunities & more.

Cheetahs have the lowest populations of Africa’s big cats, but they range over the largest area. Researchers from Panthera outfit cheetahs and other animals with GPS collars to identify corridors and monitor the cats’ movements—and protect them in real-time from poaching and other human-wildlife conflicts.

For example, Panthera can alert government officials in a region to activate a “Halo Protection Approach” when cheetahs are passing through: clearing paths of deadly snares, deploying targeted foot patrols and alerting communities so they can adapt their activities. To incentivize participation, a wildlife values program rewards communities for allowing predators to wander unharmed through their homelands.

And since most cheetahs travel in groups for a substantive part of their lives, by collaring one individual cat, Panthera provides real-time protection to the larger group.

→ Learn how GPS collars are aiding wildlife conservation in Zambia.

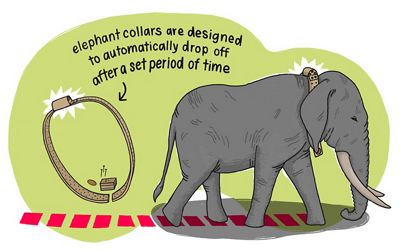

Elephants migrate seasonally between feeding grounds, water sources and breeding areas. Our partner, Save the Elephants, has collared and tracked hundreds of individual elephants in the Samburu region of northern Kenya since 1998, providing one of the most comprehensive datasets on elephant movement in any area in Africa.

This data helps identify and map key elephant habitats and the corridors that link them. Kenya’s National Environmental Management Authority uses the information to make more informed decisions on where to site future development and prevents herds from ploughing through fences, roads or farms—which can lead to elephants being killed.

→ See how elephant tracking is influencing land-use decisions in Kenya.

Rivers around the world were once filled with millions of fish swimming upstream from the ocean to spawn in freshwater—and provide food for people and wildlife and distribute valuable nutrients along the way. Now, two-thirds of the world’s longest rivers are blocked by dams, culverts and other barriers. These barriers are cutting off migrations between rivers and the sea and within river basins—and causing frightening declines in fish populations.

In recent years, scientists have been tracking and mapping these migrations using a combination of tools such as acoustic and satellite tags that ping off receiver networks, underwater cameras and environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling. Not only does this data help reveal where migration is blocked and action is needed, it also shows whether active restoration efforts are working or need attention.

One place this approach is playing out clearly is in Maine. After major restoration efforts on the Penobscot and lower Kennebec River, scientists are seeing numerous species of fish such as Atlantic salmon and sturgeon, shortnose sturgeon and alewives return to much of their historic waterways.

By continuing to analyze migration data scientists can see which fish are successfully moving through restored passages, where bottlenecks remain and where designs need improvement.

→ Explore how migration tracking is driving river restoration.

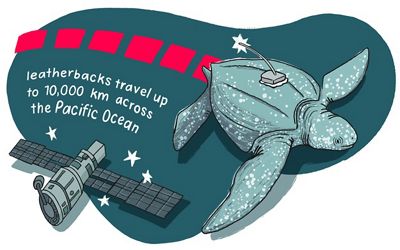

Leatherback sea turtles undertake the longest migration of any sea turtle, moving from cold northern waters to tropical nesting grounds. Researchers track these turtles using satellite transmitters attached to their shells, allowing them to follow their movements across entire ocean basins. This tracking data shows not only where the turtles travel, but also the ocean conditions they encounter.

This is proving essential for conservation efforts, as the turtles face a gauntlet of threats along their journey. At beaches where the females nest, for example, communities can be alerted to turn out lights, preventing hatchlings from being confused. Scientists can also identify overlaps with commercial fishing areas and the turtles’ feeding zones.

By pairing tagging data with collaborative management across nations and fisheries, TNC and partners can protect both nesting beaches and at-sea habitats so that these ocean wanderers have a better chance of survival.

→ Learn how satellite tracking protects leatherbacks across oceans.

This work isn’t limited to the science pros. Here's how you can help:

Log your bird sightings on eBird, wildlife observations on iNaturalist, or join local migration counts.

Turn off outdoor lights during peak migration, plant native flowers that bloom when migrants need them or remove obstacles. Check for local alerts and migration maps to stay updated on timing.

Help organizations monitoring tagged animals through networks like Motus that detect birds, bats and insects as they pass through landscapes.

TNC has plenty of volunteering opportunities, including roles that put your scientific skills to use. Get Involved