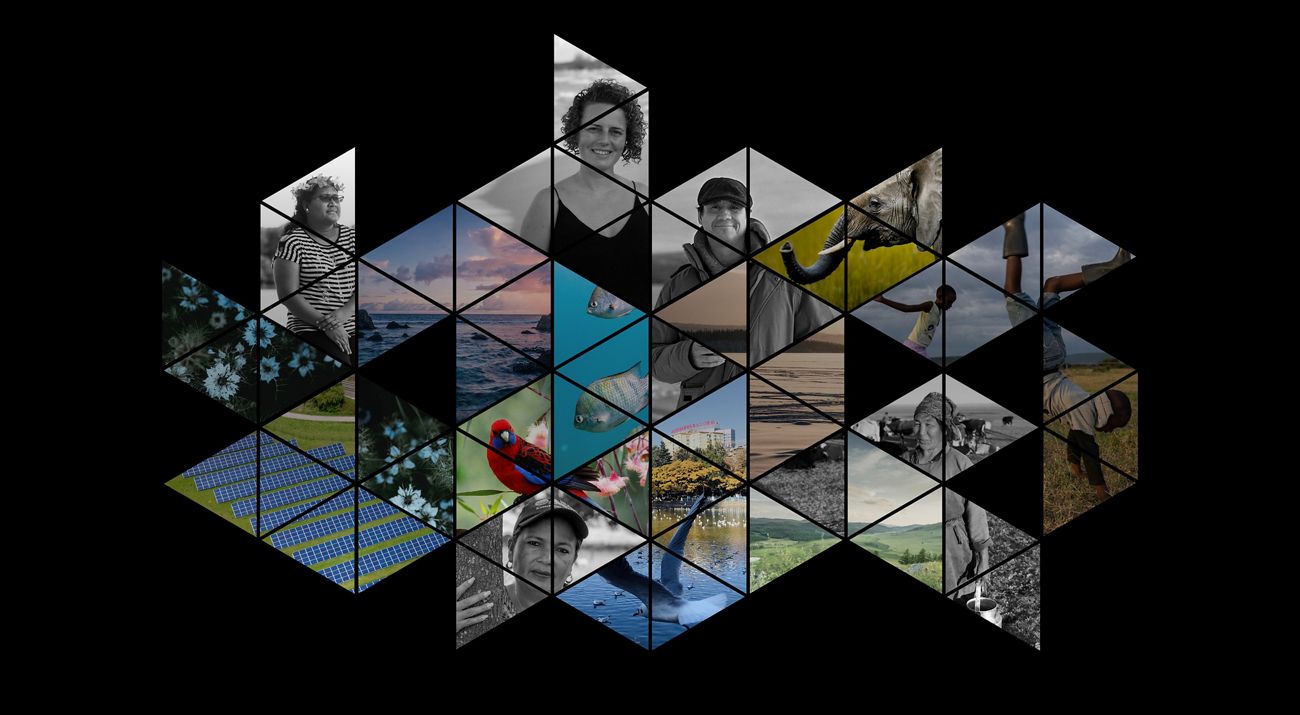

9 Places Where People Are a Force for Nature

For these local heroes, imagining a world without wildlife isn’t an option—nature is personal.

Jump to a Story

1. Canada

2. Colombia

3. Kenya

4. Mongolia

5. Australia

6. Micronesia

7. United States

8. Dominican Republic

9. China

A just, stable and sustainable world for all life. It’s the future that 2020 reminded us we really need. And while it can be hard to imagine the huge shifts it will take to get there, one thing remains certain: how essential we are to each other. People to people. People to nature. Nature to everything.

Indeed, these connections are the bedrock of our existence—when nature thrives, people thrive. But even when we acknowledge this truth on a planetary scale, it’s easy to lose sight of what that means to individual communities and individual people. Thriving means a family finding security through a new way of raising food; it’s a struggling community rebuilding its economy around climate resilience; it’s an Indigenous community once held at the margins of society stepping forward to lead ambitious national action.

People and nature find ways to thrive, together—let’s not forget what that looks like. These stories from across the globe remind us that we can achieve incredible things—but it starts with each of us acknowledging we are part of something greater than ourselves.

Canada

Where the “land of the ancestors” provides a way forward

Read More About Thaidene Nëné

Indigenous leaders achieved protection for the 6.5 million acre Thaidene Nëné, which includes Canada's newest national park, and set an example for community-led conservation.

Colombia

The restorative promise of a small plot of scrubland

Read More About Ranchers in Colombia

Displaced and disenfranchised by decades of war, some Colombians are rebuilding their lives—and their forests—through ranching.

Kenya

Will the next generation also walk with wildlife?

Read More About Maasai Mara National Reserve

Innovative lease agreements are opening up wildlife corridors and improving livelihoods in Kenya’s community conservancy areas.

Mongolia

The grasslands of opportunity, ambition & culture

Read More About Milestones in Mongolia

With both national and local government support, Mongolians have designated nearly 40 percent of their territory for protection—and communities are leading this global charge.

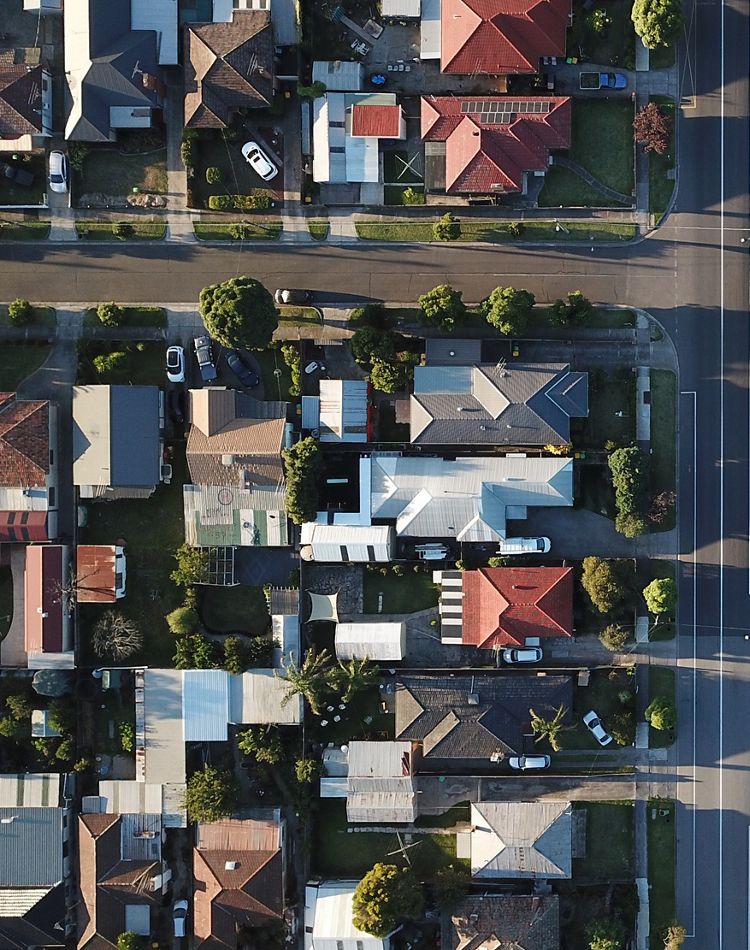

Australia

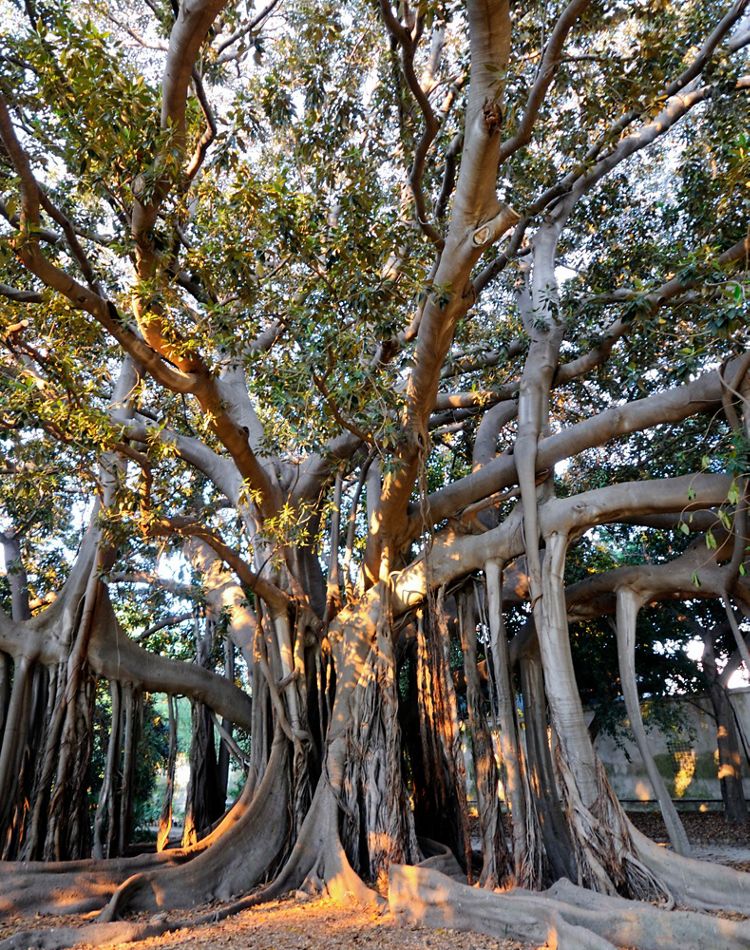

For the love of trees, a model for urban forests emerged

Read More About Greenprinting in Melbourne

Urban green spaces generate a multitude of benefits for cities—now there's a guide for helping nature flourish in communities across the globe.

Micronesia

A lesson in how to live off a rising sea, rooted in nature & tradition

Read More About the Micronesia Challenge

Since its inception, the Micronesia Challenge has achieved great success in protecting land and sea for people and nature, and it has inspired other nations to take similar action.

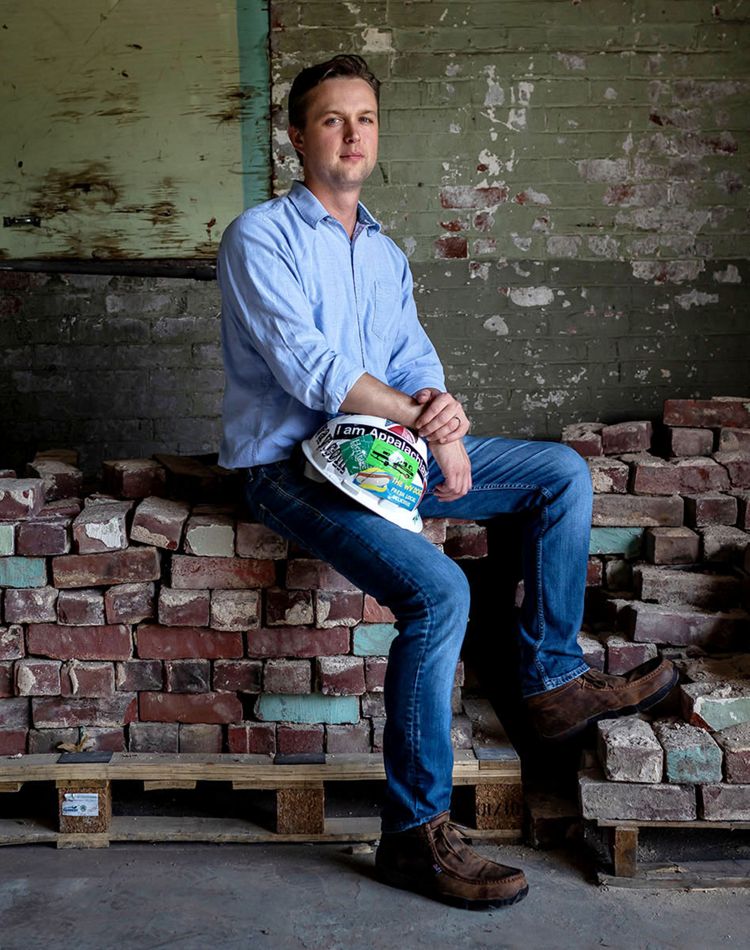

United States

Where nature and people can heal together

Read More About Renewables in West Virginia

Nevada and West Virginia, two U.S. states with distinct identities, are finding themselves on the frontier of clean energy exploration.

Dominican Republic

Changing the way we see the ocean

Read More About Coral Reefs in the Caribbean

A breakthrough in aerial mapping technology is bringing new clarity to reef protection in the Caribbean.

China

Where the world will come together, and leaders will emerge

Biodiversity Action Guide

The Biodiversity Action Guide offers key strategies for increasing biodiversity conservation that are scalable—focused on protecting intact natural systems and inclusive of authentic community partnership. The guide highlights 14 real-world examples from around the globe to show how partnership with public and private sector leaders can achieve ambitious conservation targets.

Get the Guide >

People around the world are adding their voice to call for urgent action. Sign the Voice for the Planet pledge:

Join the Conversation:

Global Insights

Check out our latest thinking and real-world solutions to some of the most complex challenges facing people and the planet today.