Planning for the Prowl: Why it’s Rush Hour for the Florida Panther

Each of Florida's endangered big cats needs 50 - 200 square miles to roam. New housing developments and shopping centers are fragmenting its habitat.

“Hold on one sec, I’ve got a lot of layers here.”

Brent Setchell is walking me through the southwest Florida landscape via Google Earth Pro, pretending to be a Florida panther on the prowl.

While the endangered big cat goes off of instinct, Setchell has the luxury of flipping through mapping software that knows each building, farm, conservation land, road, culvert, canal and animal crossing in the state. It also knows where every panther has been struck and killed over the past several decades.

There are few perfect pathways.

He highlights a particular route connecting the Peace River to the Green Swamp south of Interstate 4, the Tampa-Orlando connector. “You’ve got some good conservation lands but you’ve got a junkyard here, a gun range here and a landfill here, so the smell coming off there is probably not the greatest.“

It’s a forward-thinking exercise–not many panthers today have even made it this far north. But given that the state almost lost the panther forever, there’s reason to be proactive.

Urge Congress to Act

Without strong funding for LWCF, habitat protection for the panther is in jeopardy.

Help Save PanthersFrom extinction to a rebound

Eradicated from the rest of the eastern United States by hunting and habitat loss, the last 20 or so panthers inhabited the dark green swampland of the Everglades and Big Cypress in the 1970s and 1980s. There may have only been 3 females left, caught in a cycle of inbreeding that pushed them closer to extinction.

The answer was up in the air… literally.

Federal and state agency officials went to the extraordinary length in the 1990s of airlifting 8 female pumas from Texas (the Florida panther is a subspecies of the puma) and temporarily releasing them in Florida to deepen the gene pool. The intervention was successful–over the next two decades, the Florida panther’s population jumped to around 200.

A completely different Florida

But in the half century when the panther was at its low point, the Florida it reigned over changed substantially.

In 1960, as the Florida panther retreated, the state’s population was just under 5 million. As the panther makes its grand return, it must survive in a state with a population over four times that amount.

Year-round warm weather and a lack of state income tax are luring 900 to 1,000 people to move to the state every day. That requires a lot of housing, asphalt and cars.

While habitat continues to fragment, even the panther’s traditional stronghold is becoming a tough place to live, thanks to human activity.

“It’s become harsher down there in the Everglades,” says Darrell Land of the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC). Land, who’s played a leading role in Florida panther conservation for decades, says invasive Burmese pythons may be affecting the prey base and water projects might be isolating the big cats into small islands of trees in the wetlands.

The irony is that if Florida hadn’t yet been built up and if we could’ve given the panther first pass at habitat, it would’ve actually preferred exactly where the Miami-Palm Beach metropolis is built. “The better habitat would’ve been along the Atlantic coastal ridge forest, more of the upland,” says Land. “Now it’s all concrete.”

More change could be coming. Florida is currently studying whether a new toll road cutting from Naples to Orlando, through the heart of panther country, is viable. The Nature Conservancy (TNC) is one of four environmental organizations participating in a task force with the state to evaluate the impact such a road could have on wildlife as well as water quality. The best-case scenario from TNC’s perspective is for the road to never be built.

A creature that needs space

According to the official recovery plan from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, there would have to be three separate breeding populations of at least 240 cats each before the panther could be removed from the federal Endangered Species list.

Florida panthers don’t read government documents, but they do know they need to roam far and wide; it’s part of how they’ve evolved.

Female panthers roam on a range of around 50 square miles, while male panthers need four times the space. Males move farther in order to maximize chances to mate with females and to meet their caloric goals without losing their prey.

“When you’re hunting large protein packages, you can’t put so much pressure on the deer as your food source,” says Land. “So at any given spot they’re not all just hanging there until they get the last deer. This allows the deer to reproduce and make up for the losses.”

The race to conserve a wildlife corridor

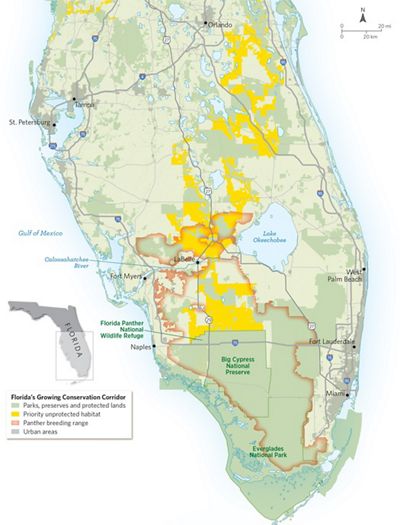

Knowing that the big cat needs to move, nonprofits as well as state and federal agencies are racing to identify and conserve natural land that can be used as a pathway northward through the state.

The Nature Conservancy has been the face of land protection in Florida, not just for the panther but for other species, says Wendy Mathews, TNC’s conservation projects manager in Florida.

“When we protect a piece of property that’s within panther country, we’re also protecting habitat for gopher tortoises, scrub jays, rare plants, and water quality.”

Through a series of conservation wins, TNC recently secured a path for the panther across the narrowest stretch of the east-west Caloosahatchee river, which, coupled with busy nearby roads, has been a formidable barrier to the journey north.

“I’m gonna run to that clump of trees.”

Even with conservation lands, there’s still the issue of cars. “In the panther’s world, big things [like cars] don't move this fast,” says Land. “You only get a chance to learn the lesson once, and if you learn it you’re dead. You have no skillset to pass on.”

Setchell would rather the panther never have to learn that lesson. His team designs wildlife crossings to protect the animals as well as Florida’s drivers.

Setchell’s district covers most of southwest Florida, which happens to be ground zero for the expansion of the Florida panther’s range. It’s not until an hour of talking to him about the scores of wildlife crossings his team has worked on that I learn what his day job is.

“We do what we can with the limited time and resources we have. This isn’t even my title,” says Setchell. “My title is district drainage engineer, so I just get to do this for fun when I have free time.”

Yet because he focuses on drainage under roadways, he has opportunities to make sure there’s space for wildlife like the panther. Mathews and the TNC team conserved land on both sides of the crossing Setchell worked on under State Road 80, which can ensure the crossing is as successful as possible.

“There’s natural light coming through, which is kinda inviting,” says Mathews. “And then on the other side, there’s dense vegetation, which is also inviting. So from south looking north from a panther standpoint you’re like, ok, I’m gonna run to that clump of trees.”

If fewer panthers get killed and end up living longer into their reproductive lives, it could accelerate the cat’s recovery exponentially.

That is, only if we plan a place or path for them to live.

The ghost of Christmas future

It's more than just roadways, says Setchell. “It's going to take land use changes as well to preserve those lands. And then it's going to take partners like TNC that can purchase or manage lands and help incentivize developers to go in a different direction.”

As you move north through the central heart of the state, where traditional industries like ranching and citrus are seeing decreasing profit margins, a chess match is quietly taking shape between developers and property owners.

“We need to help out these landowners because the fastest way they can make a buck is to turn that ranch into the next suburb, where panthers will not be raising kittens,” says Tim Tetzlaff, conservation director at the Naples Zoo.

The key is to be out in front of the panther.

“Where panthers are north of the river now is where we were 30 years ago in the south,” says Tetzlaff. “And so we've seen the ghost of Christmas future. This gives us a chance to try to do it differently as panthers move north.”