With the global population likely to reach upward of nine billion people by 2050, it may seem as though environmental protection and human development are destined to remain at odds. After all, in many places our expanding energy, food, mineral and transportation needs have already devastated the variety of life on Earth—and current projections indicate development pressure will only grow, putting even greater demands on natural lands and waters, and the species that live there.

But protecting nature is also vital for the health and prosperity of people. As Indigenous communities around the world show us, it is possible to live in harmony with nature. With a growing world population and rising demand for food, housing and energy, however, creating policies to prevent the degradation of intact habitats can get tricky.

Mitigation hierarchies can help stakeholders navigate difficult decisions about development and its impact on nature. The key idea is to avoid impacts wherever possible, but create plans and standards to reduce and compensate for impacts that do occur:

-

Avoid biodiversity impacts

the most important step

-

Minimize impacts

when they can't be avoided

-

Restore ecological function elsewhere

the last resort, ideally implemented in a way that achieves a net gain for biodiversity

In fact, all 196 countries party to the UN Biodiversity Convention and 116 of the world’s leading financial institutions have actually pledged to hold new growth accountable to a biodiversity mitigation hierarchy. That may sound like good news, but not so fast:

-

42

42 countries have made biodiversity compensation a regulatory requirement.

-

66

66 countries have established other strategies for compensation.

-

9

Yet only 9 countries are currently implementing them. This needs to change.

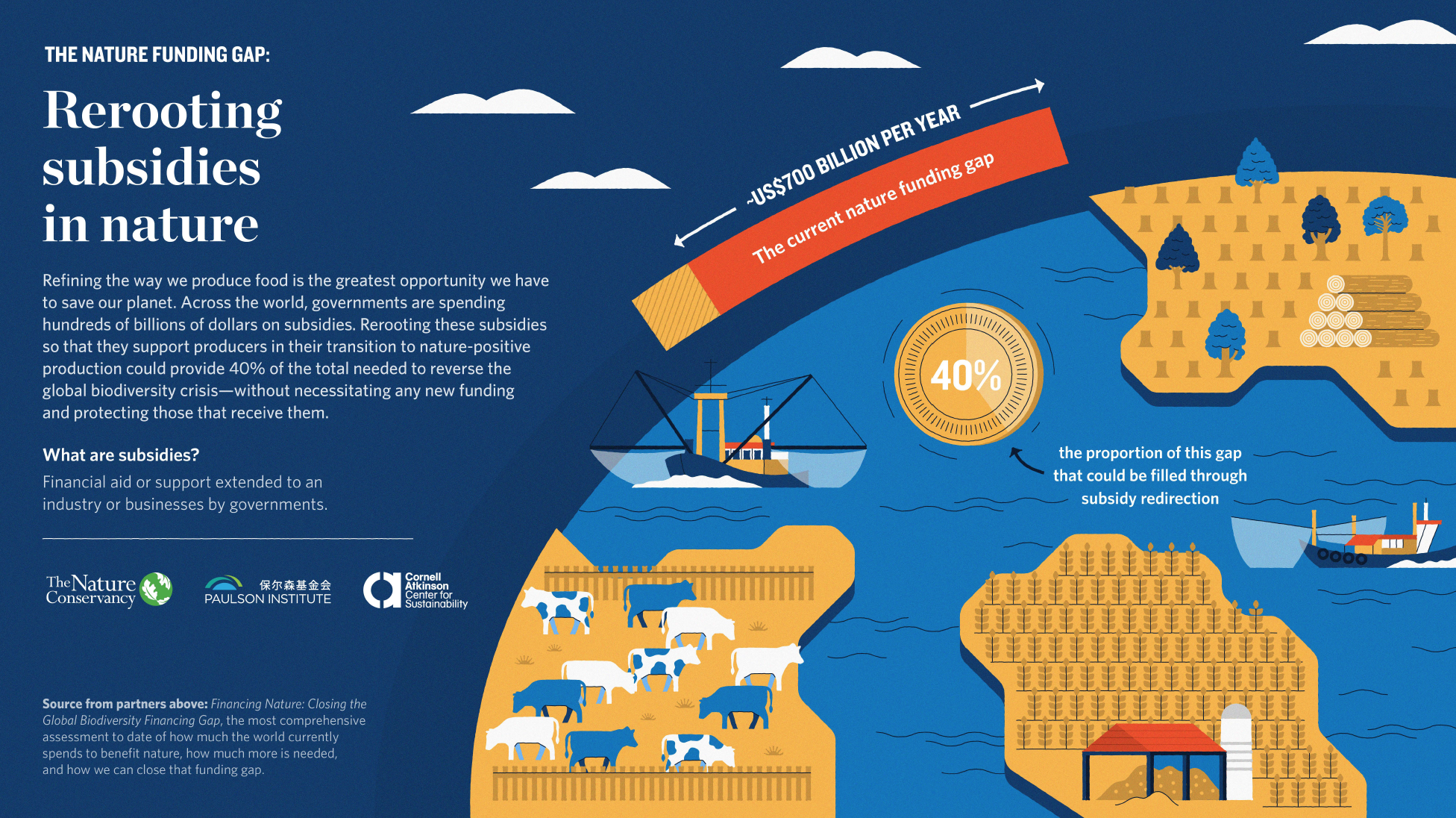

Implementing more robust mitigation schemes that include biodiversity compensation—the restoration of habitats to make up for new losses—is an important part of achieving the net gain for biodiversity that all life on Earth needs. The world is currently spending US$6-9 billion on compensation expenditures—only about 5 percent of the funding needed to compensate for development impacts on biodiversity. That leaves a $700 billion nature funding gap.

So we know governments and financial institutions need to work on implementing the standards they’ve signed on to—but how?

Case Study: Mongolia

Consider Mongolia’s predicament. In recent decades, a mining boom has put pressure on its precious natural lands, endangering the nation’s claim to the largest steppe ecosystem in the world: the Central Asian Gobi Desert.

This new sector soon accounted for a big chunk of the country’s GDP. With many people living below the poverty line, Mongolian livelihoods depended on it.

But Mongolians also wanted to protect the nation’s untold natural wealth. To balance out rapid growth in mining and related infrastructure, the government recently committed to protecting 30 percent of all its natural lands—195,000 square kilometers, an area the size of Senegal, or larger than Portugal and Iceland combined.

Not just any lands, either: the government has ensured the protected lands represent the full distribution and diversity of Mongolia’s native species and ecosystems across 50 sites.

And when it came to making this work in practice, a clear mitigation hierarchy was crucial:

Our global insights, straight to your inbox

Get our latest research, insights and solutions to today’s sustainability challenges.

Sign UpImplementing systems of mitigation hierarchy and biodiversity compensation is more important now than ever. We know that biodiversity loss and climate change represent urgent threats to global health and prosperity, but protecting and restoring nature will require us to mobilize significant funds.

As the global economy emerges from a pandemic-induced slump, we have an enormous opportunity to rethink how and where money is channeled—yet to date, only $1.8 trillion of an estimated $17.2 trillion in stimulus funds has been green enough to reduce greenhouse gas emissions or enhance biodiversity. More of that funding must be set aside for strategies that help people and nature.

With global leaders set to renew biodiversity and climate commitments later this year, now is the time for governments and the private sector to increase ambition to meet the crises—and once-in-a-lifetime opportunities—at hand.

Download these digestible infographics to learn about more innovative mechanisms that can help fund a sustainable future, including carbon markets and agriculture subsidy reform.

Download the Infographics

-

Building Better for Biodiversity

PDF

Biodiversity compensation requires developers to make a simple pledge: make biodiversity retention a top priority, and when destruction is truly unavoidable, restore a similar ecosystem of at least the same size, health and ecological value to ensure 'net-gain' for nature.

DOWNLOAD -

Unlocking Funding to Lock Up Carbon

PDF

Our planet faces two urgent and interconnected crises: biodiversity loss and climate change. But there is hope. By better protecting, managing and restoring natural ecosystems, we can tackle both problems at once.

DOWNLOAD -

Rerooting Subsidies in Nature

PDF

Refining the way we produce food is the greatest opportunity we have to save our planet. Across the world, governments are spending hundreds of billions of dollars on harmful subsidies.

DOWNLOAD

Global Insights

Check out our latest thinking and real-world solutions to some of the most complex challenges facing people and the planet today.