Catalyzing Carbon Projects in Africa

Q&A with Charlie Langan, TNC's Africa Region Carbon Market Director

This story is part of our Living Carbon series, covering the power of natural climate solutions for communities, biodiversity and the planet. > Explore the Living Carbon stories.

Africa has one-fifth of the world’s remaining forests, but is losing them fast. Projects that keep forests healthy not only help remove carbon from the atmosphere, but also help communities overcome growing climate impacts such as flooding and drought. Learn more about The Nature Conservancy's work to protect Africa’s living carbon with Charlie Langan, Africa region carbon market director.

Carbon projects are on the rise, but they are also widely misunderstood – how do they work and why are they so important?

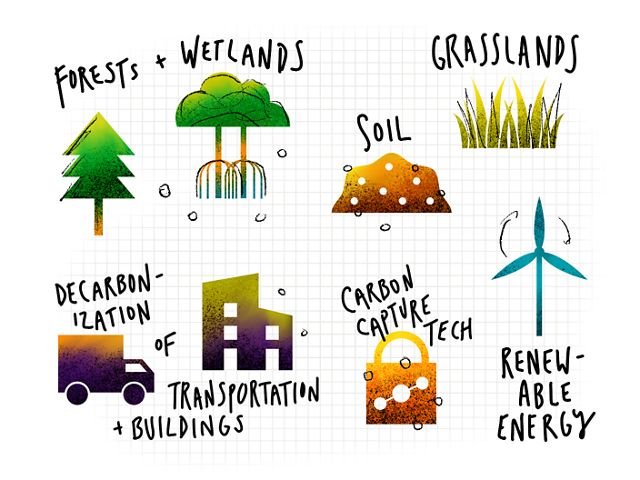

Charlie Langan: Carbon projects are designed to maximize nature’s contribution in the fight against climate change. By protecting and restoring forests, grasslands, and other ecosystems, we can increase their ability to absorb and store carbon. This increased carbon storage can be measured and turned into carbon credits, which leading companies and individuals can buy to help them meet their climate goals.

But it’s important to stress that companies must first make urgent investments in reducing the carbon emissions of their own business and operations and then use carbon credits to offset carbon pollution that remains. When companies use carbon credits to clean up emissions that they otherwise don’t have a solution for, it can create big wins for the climate, for conservation, and for local communities.

One challenge is that so many people don't really understand how carbon markets and projects work. There is a perception that companies are buying carbon credits instead of reducing their emissions. This is a real risk, but TNC is working closely with other NGOs and partners to set new rules and best practice for voluntary carbon markets to make sure companies are first reducing their own emissions, and then using carbon credits to address the rest.

Quote

Carbon projects are designed to maximize nature’s contribution in the fight against climate change.

Another real challenge is the need to create enough high-quality carbon credits to meet the demand of this rapidly growing market. TNC has been leading for years in creating the science and best practice needed to make sure carbon projects produce the best outcomes for the planet and people. We’ve recently redoubled our efforts here with a whole new global team focused on just that.

Just as importantly, conservation practitioners around the world need to be empowered to access carbon markets and use them to build more successful conservation projects. Because a carbon project is essentially a good conservation project done right. The carbon element just sits on top of the conservation work and can provide a valuable, long-term sustainable financing mechanism that lasts over 20 or 30 years.

As long as you can generate and measure the impact in terms of either reducing or removing carbon emissions, you can generate revenue by paying for this performance to feed back into communities and conservation action in the landscapes. This is exciting stuff, as it’s pretty unheard of in traditional conservation grant structures to be able to set up financing with that kind of longevity. Usually, halfway through a 5-year project you need to start thinking about where the next pot of money is coming from.

In addition, it’s vital for carbon projects to have a clear conservation vision, an adaptive management plan, and a strong monitoring and reporting system as that is what generates the sustainable revenue stream through payment for performance. That’s why TNC set up the Global Carbon Market Team to oversee engagement and has developed a set of standards for high quality carbon offset projects based around three principles: robust carbon accounting, maximizing returns and benefits for communities, and the responsible use of offsets. The goal is to drive quality in the carbon market to ensure its integrity and to massively scale up effective, community-led natural climate solutions (NCS).

Do you envisage carbon projects taking off in Africa? Where do you think they have the most potential on the continent?

Charlie Langan: Everywhere! Africa has one-fifth of the world’s remaining forests but is losing them faster than anywhere else. There is vast untapped potential here, in addition to the huge impacts these projects can have on community sustainable development in areas of high poverty incidence and biodiversity hotspots. Plus, there is substantial need to help people and nature adapt to and overcome the real impacts of climate change already occurring today. Natural climate solutions provide adaptation benefits while at the same time reducing carbon emissions by protecting the forests that absorb carbon.

That’s why we launched the Africa Forest Carbon Catalyst early last year. It’s a $10 million grant raised with the idea that we will provide technical and financial support to TNC programmes and partners to develop high quality carbon projects. The goal is to develop a pipeline of bankable carbon initiatives to show they can deliver conservation, community and financial returns, to encourage others to replicate the model, and together achieve large scale wins for climate, biodiversity, and livelihoods across Africa.

Quote

Africa has one-fifth of the world’s remaining forests but is losing them faster than anywhere else.

Many of the first cohort of projects have advanced quickly; they have now graduated and are attracting further investment to scale and operate. We just started another nine projects this year, but they are at a very initial stage. In a couple years there will be some great stories to tell, but it’s still early days in the carbon project space in Africa.

So far, the portfolio we're working with spans TNC’s key geographies of Kenya, Tanzania and Zambia, but we are also looking to develop projects in Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo, and we’re reaching into Sierra Leone and Nigeria.

The projects include: forest protection and restoration; protection of “blue carbon” stored in mangroves and other marine systems that store carbon on the coast in Kenya; and a new project in Sierra Leone that’s looking at farmed landscapes and encouraging small holders to do on-farm tree planting and agroforestry alongside traditional cultivated crops. And up in the northern Kenyan rangelands a project is working to improve communities’ grazing management to increase soil sequestration and lock more carbon into their soils, which is great for grass productivity, biodiversity and water management across the landscape. It's hugely diverse and there's huge potential.

What are carbon offsets?

Carbon offsetting entails reducing or removing greenhouse gas emissions in one place to compensate for emissions elsewhere. Through carbon markets, carbon offset projects can sell or trade a carbon credit for each metric ton of carbon dioxide (or equivalent) to emitters to help accelerate overall carbon reduction goals.

> Check out Carbon Offsets, Illustrated.

How are the carbon credits that a project earns calculated?

Charlie Langan: A carbon credit represents the measured impact a project has. To measure the impact, projects need to establish a counterfactual baseline scenario of what would happen in the absence of a project, and then measure the project’s impact against that. A project baseline is based around what has historically happened, so we look at forest changes in an area and say, for example, that there’s been 2% forest loss in this region every year without the project. Then we make a forecast that we can protect 90% of that forest through different interventions – like community livelihood programmes, governance training, or enforcement through community rangers – and that impact will maintain the carbon stock at a higher level. The difference between that level and the baseline is your impact, which is what you get issued carbon credits for, measured in tonnes of CO2.

Every year or couple years, you collect all the impact data into a monitoring report, undergo a rigorous audit by an approved carbon auditing firm, and take that to the carbon standard to verify and issue your carbon credits. At that point you can sell those carbon credits to corporations looking to offset their emissions and you start generating revenue back to the project. Traditionally, carbon credit prices have been quite low but they are picking up quite rapidly now, which is creating incentives to set up carbon projects.

Video: How carbon markets fight climate change

If we want to keep the climate in safe boundaries, we need to reach net-zero emissions as soon as possible. But eliminating some carbon sources will be easier than others. That’s where carbon markets can help. > See the video (2:45)

Who are the main beneficiaries of the carbon projects in Africa and what opportunities can they bring to the communities in these landscapes?

Charlie Langan: The way carbon markets work is that it's pay-for-performance and largely it’s the communities who are making the behavioural changes that generate the climate impact and drive that performance – in the form of emissions reductions or removal. These changes usually involve costs due to shifting their land management practices and agreeing to plans to protect or restore their forests or mangroves, but communities also benefit from increased environmental health, such as more productive soils in rangelands, and reduced flooding and erosion.

Alongside this, projects also introduce incentives, including alternative livelihood programmes so people can improve their ability to grow food or run small businesses without cutting down trees, in addition to direct cash transfers to individuals or communities, for example through payments into village savings. A good carbon project should make major investments in communities to help them meet their development goals in a way that also protects nature and its ability to fight climate change. Conservation groups can also benefit due to the conditional financing entering landscapes to address conservation challenges. And finally, carbon offset buyers benefit by being able to fund effective and measured action to tackle climate change.

Quote

A good carbon project should make major investments in communities to help them meet their development goals in a way that also protects nature and its ability to fight climate change.

What steps are being taken to make sure project benefits flow to the local communities?

Charlie Langan: Benefit sharing is a negotiation with the land rights holder, which in Africa is often communities themselves. Communities need to be consulted to ensure they are ready to voluntarily change certain behaviours and practices in return for agreed benefits. As communities are the ones who take the action to protect the forest, grassland, etc., it is fair that they should also get the majority of benefits.

In addition, communities need to be consulted on how to deliver benefits in a transparent way that is understood and equitable within the community, and that doesn’t exacerbate existing inequities. And it is important that these benefit sharing decisions are made up front through a democratic process, documented in legal agreements between the project operator and communities, and communicated transparently.

Another factor is that project success is often dependent on local conservation groups providing the enabling environment conditions and investments in the landscapes, such as by strengthening community governance structures, developing land management plans, and monitoring project impact. These landscape actors must also be fairly rewarded for their performance in creating climate impact. A core pillar of the quality criteria we‘re working towards is maximizing returns back to landscapes for communities and conservation, and making sure that benefit sharing is equitable and fair.

Our global insights, straight to your inbox

Get our latest research, insights and solutions to today’s sustainability challenges.

Sign UpWhat are the risks you need to look out for when working with carbon markets? What problems have you encountered?

Charlie Langan: At the wider carbon market level, there are a couple important risks. It is only in the last year that these markets have received the investment they need to really mature, so some challenges remain, which TNC is really focused on. As mentioned earlier, we need to make sure that companies only use carbon credits after taking ambitious action within their own business to reduce carbon emissions, like reducing flying, improving energy efficiency, food policies promoting low carbon impact food, buying EVs, changing to renewable energy, etc. This is critical to make sure society invests in the new technologies needed to address climate change. There is also the challenge of making sure the rules for carbon markets continually use the latest science and best practice, including best practice for community participation.

A key risk factor here is money. A big challenge we have at the moment is that there's a lot of capital moving into the carbon market space, and inevitably not all of it is useful, fair and equitable. One of our concerns is that a fair investor return and the carbon credits’ transaction value returns to the continent. Another is how to ensure alignment between robust carbon accounting and project financing structures. AFCC is supporting projects to develop strong and creative financial models that really set out the different costs and where the revenue from the credit sales will be redirected, in a way that maximizes returns into communities and landscapes. That’s why a key part of what we do is building up technical capacities and expertise in local conservation groups.

These are large complex projects so they can experience the same challenges that any large conservation or economic development project might encounter. However, due to the increased scrutiny and impact monitoring required for carbon projects, we are more aware of the challenges than with many other conservation or development projects. These include issues around policy, community engagement, community negotiations, respecting human rights, and making sure that everyone is being fairly rewarded.

On top of all this, if you already have challenges over village-level governance mechanisms that are meant to be responsible for the management of community’s rangelands, when you bring money from the carbon markets into that situation things can quickly go off track because there is a suddenly a huge cash injection. It’s vital to be aware and be thinking through the potential risks when developing these projects, and to really collaborate with communities so they are fully informed and influencing the project design to maximize likelihood of success. It’s also important to be cautious and patient to set the project up correctly – recognizing that it takes time and money to achieve.

Quote

It’s vital to ... really collaborate with communities so they are fully informed and influencing the project design to maximize likelihood of success.

Have you found local people are enthusiastic about these carbon projects; what kind of reactions do you get when setting up a new project?

Charlie Langan: The responses can be quite mixed. Some communities are not very receptive and understandably skeptical of what may sound to them like a far-fetched concept, while others appreciate the opportunity and prefer the performance- reward approach. What’s really important is to help put communities in the driver’s seat so they can choose whether to engage. So, the reception is diverse, although often the inertia is rooted in a lack of understanding or suspicion until project benefits start flowing.

We also need to engage and discuss with national governments to make sure what we are doing is a) legal and b) compatible with their climate and land use commitments, policies and tax laws -- because at a stroke of a pen they can basically annul a carbon project. But, overall, governments are very receptive because they can see the foreign exchange and private foreign investment pouring into the country as well as the benefits to climate, land and people.

With so many different projects just starting out, where are the most exciting new areas to watch out for?

Charlie Langan: It’s hard to choose as we have lots of great projects under development.

One that really excites me is the expansion of the Northern Tanzania Rangeland Initiative – a TNC-supported long-term programme and coalition of conservation partners in northern Tanzania, where we have demonstrated how rangeland health and traditional pastoral, cultural and biodiversity conservation are interlinked. Underlying rangeland health is soil carbon, so avoiding overgrazing and rangeland degradation can generate carbon impacts and a long-term revenue stream to support ongoing grazing management and community livelihood programmes.

Another is in Sierra Leone, where we’re just getting started with a project to support community-led protection of mangroves. We’re beginning with some early studies, but if it goes well then there’s the potential to scale up across neighbouring countries in West Africa.

Equally, we’re looking at a big project in DRC to create a giant corridor to link four isolated nature reserves through a new community-led nature reserve, which is a pretty new approach to conservation in DRC. The scale of that project is so vast and has a huge potential benefit and revenue stream to support not only community-led nature reserve governance but also wider development in a very rural part of DRC that is chronically under invested in.

What's the vision for the future - where do you hope to see carbon projects in Africa 5 years or 10 years from now?

Charlie Langan: Right now, we're focused on building up best practice case studies to demonstrate how to do high-quality NCS carbon projects that protect carbon market integrity and follow our three principles: robust carbon accounting, maximizing returns to communities, and responsible use of offsets. A big part of that work is making sure the technical support and appropriate financing is there for these projects.

Our success metrics also include seeing carbon market literacy grow across Africa, starting with local enterprises and local conservation groups. We can then help these local groups develop carbon projects, and make sure the financing available is much more competitive and brings greater returns to landscapes. Those are the key metrics of success we want to see across Africa – increasing carbon market literacy, high quality carbon projects, and lowering cost of financing for these projects. That way we can build the momentum needed achieve the ultimate goal of scaling up these natural climate solution projects throughout Africa.

By 2025, the Africa Forest Carbon Catalyst aims to support projects that cumulatively avoid or reduce 20 million tonnes of CO2 emissions a year, restore or conserve 10 million hectares of forest, and improve the livelihoods and well-being of 500,000 people in communities across the continent.

Living Carbon:

Stories of Nature's Climate Solutions

In this series, we showcase innovative carbon projects in Africa, northeastern Pennsylvania, Chile's Valdivian Forest, and the Emerald Edge along North America's Pacific coast.